Release date: 7/5/41 (according to BCDB); 7/12/41 (according to Michael Barrier's Hollywood Cartoons)

DVD/BR AVAILABILITY: Looney Tunes Golden Collection, Vol. 2; as a part of the film What's Up, Doc? A Salute to Bugs Bunny, Pt.1 on LTGC Vol. 3; Looney Tunes Spotlight Collection Vol. 8 (all Warners Home Video DVDs)

You may view a crisp correct-ratio print of this cartoon HERE. The screen grabs are provided by our great pal Devon Baxter, and make this frequency of posting possible. Please check out and support Devon's Patreon page. He's doing superb work in determining who did what in these classic cartoons, where the film credits usually bely the artists who worked on them.

<><><><><><><><>

Thanks to Martha Sigall, a member of Schlesinger's ink and paint department who related her memories of the studio prior to her 2014 passing, we know that Avery and Schlesinger butted heads over the original ending. In her memoir, Living Life Inside the Lines: Tales from the Golden Age of Animation (Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2005), she recalls the conflict:

Then he opens them, sees us, and irritation registers on his face.

He reaches up...

...and pulls down the series title card like a windowshade.

good luck and departs--casually and slowly. There's no need to hurry or worry.

"Dah...h-hey...

"...that was da rabbit!"

With tense anticipation, Willoughby explodes into action.

Dry-brush beauty in action.

To another Stalling fave, "The Fountain in the Park,"

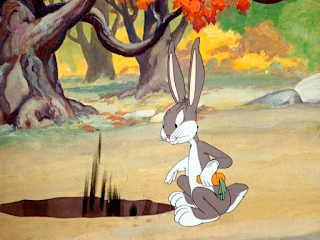

Bugs saunters carefree, his carrot brandished like a cigar. He dips below

to evade the canine holocaust with perfect timing.

Devon Baxter: This should be displayed at the Louvre (re: frame above)

Bugs takes quick assessment of scene, then returns below.

with attendant distortions by Scribner.

As said earlier, Bugs wouldn't indulge in this daffy-for-daffy's-sake behavior much longer.

Willoughby follows with surprising grace...

...for a moment.

..,and into a tree.

Bugs' glee is a mite disturbing.

Offstage props are there for the asking.

The above wail is purely heart-rending.

The rocky road of this production is part of the Tex Avery legend. It gave Avery a reason to split with Leon Schlesinger. Avery would leverage this walkout into a high-berth position at M-G-M, where he would do his finest, most lasting and most maligned-on-home video material.

Through 1940, Avery was on solid footing at Schlesinger's. His hand in the refinement of Bugs Bunny, an instant audience favorite, helped push the Warner Brothers cartoons to the top of the Hollywood heap. His comic travelogues were popular enough to inspire imitations by other studios. Avery's influence in comic timing, technique, audience inclusion and the refinement of the wise-guy and dimwit archetypes, among other themes and concepts, had affected all his rivals, from Disney to Terrytoons. He was sitting pretty and, it appears, anxious to move on--and upward.

The Heckling Hare brings Bugs Bunny and Avery's spoof on Lon Chaney Jr.'s portayal of Lennie Small (from Of Mice and Men) together. It's an inspired pairing, and it allows Bugs to play to his strengths. Box-office wise, it's a boffo concept.

Avery used the finale of the cartoon to push his test of audience patience to its ultimate limit. He went too far from the comfort zones he had tested and stressed, and it didn't sit well with the front office. The ending was cut. In the released film, it's obvious something is missing.

Thanks to Martha Sigall, a member of Schlesinger's ink and paint department who related her memories of the studio prior to her 2014 passing, we know that Avery and Schlesinger butted heads over the original ending. In her memoir, Living Life Inside the Lines: Tales from the Golden Age of Animation (Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2005), she recalls the conflict:

The incident rated an article in the July 2, 1941 (not April 2, as has been widely reported and referenced) Hollywood Reporter. Animation historian Don Yowp unearthed this rare article and shares it with us here:

Another trade journal, The Film Daily, reported on the altercation in its July 10, 1941 issue, which Devon Baxter found and has kindly shared with this blog:

Put on four weeks' suspension, Avery left the Schlesinger studio for good. But Heckling Hare and its cuts weren't the real problem. Avery had a concept for taking live-action film of animals and superimposing animated mouths on that footage. He apparently envisioned having someone (perhaps Kent Rogers) do vocal impersonations of film and radio celebrities. Thus, working after hours and on his own time, he put together the debut film in the Speaking of Animals short subjects series, Down on the Farm, which co-credits Warners storyman Lou Lilly as director with Avery.

With a recognizable cast of animation voice actors, standard corny jokes of the kind he used in his travelogue spoofs, and concrete proof that Avery was better off directing animated films--he is at the whim of the slow natural movements of his critter cast--Down on the Farm was nominated for an Oscar, and led to a long-lasting series distributed by Paramount Pictures.

Avery has sole credit for the third film in the series, In the Zoo, but by September of 1941, he was signed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer to an initial five-year contract. We are fortunate that his career took this path. Speaking of Animals spanned 50 films and lasted until 1949, so it must have pleased audiences and/or exhibitors. It was a waste of Avery's talent as a moviemaker. Avery got this bugaboo out of his system and returned to a medium over which he had full control--the environment where his comedic ideas could blossom.

Avery's departure left several cartoons in varying stages of completion. It has been said that All This and Rabbit Stew, Aviation Vacation and The Bug Parade were completed on his end before the split, with Wabbit Twouble, The Cagey Canary, Aloha Hooey and Crazy Cruise finished by Robert Clampett, who inherited the Avery unit and its top-notch animators.

All this historical prelude, in whatever level of accuracy it exists, is worth knowing. But the film has to speak for itself, and it has a lot to say.

It begins with an innovation that remained through Bugs' career as a screen character. As the familiar strains of "Merrily We Roll Along" burst into life, Bugs sits atop the Warner Brothers shield as it zooms into view.

He chews his carrot, his eyes closed in contemplation or indifference.Then he opens them, sees us, and irritation registers on his face.

He reaches up...

...and pulls down the series title card like a windowshade.

This routine was re-animated at least twice (including a particularly fey Chuck Jones version in the late 1950s) but its presence remained as a reminder of the comedic sensibility that helped push animation into new frontiers. It's easy to take for granted, as we've seen it so many times since childhood. But it is a powerful statement that deserves a moment of our contemplation.

Here, through Bugs Bunny, Avery confronts us. Bugs is here; he's not happy with that; he'd rather be doing his own thing. But for the next seven minutes, he will own this screen and there's nothing you can do about it. Popeye just toots his pipe with a crowd-pleasing smile; Woody Woodpecker cavorts harmlessly. Bugs nails us with his contempt.

Credited storyman Michael Maltese, whose last Avery collab was the woebegone The Haunted Mouse, would become animation's wittiest and smartest writer by the end of the decade, when his collaboration with Chuck Jones yielded a succession of brilliant cartoons. The characters and conflicts in The Heckling Hare are in Avery's wheelhouse, and it's hard to detect what Maltese brought to the picture.

Bugs' shadow is cast diagonally across the credits, his arms bent at the elbow and fists balanced on his hips. It's an aggressive pose and furthers the opening bit's intention that we have lost control of our viewing experience. It's all on Bugs, and he intends to give it to us.

To a swingy rendition of "A-Hunting We Will Go," a mock-multiplane shot reveals Willoughby, the dim dog voiced by Kent Rogers, in imitation of Avery's vocal takeoff on Lon Chaney Jr., as he snurfs his way across the forest floor. Like many Avery openings, it's lackadaisical. Virgil Ross animates this opening saunter.

Given enough time, the nickel drops.

"Duh... a rab-bit hole..."

Carl Stalling is fond of "The Umbrella Man," written by James Cavanaugh, Larry Stock and Vincent Rose and a 1938 record hit by Kay Kyser and His Orchestra:

It proved an ideal underscore for sneaking and pussy-footing, and served for cute and lummox-type characters. It's high on the list of Stalling's go-to cues.

The jut of the dog's jawline reveals the director's hand. This is a very Avery profile, as filtered through the artistic sensibility of Robert McKimson, who did many character designs for Avery's late Schlesinger films. As I've stated before, Avery's cartooning style resembles balloons tied together. The final still, where Willoughby peers into Bugs' hole, is particularly redolent of this touch.

We and Willoughby are rewarded upon arrival. We're only 52 seconds in!

The next shot, also animated by Ross, again reveals Avery's hand as layout artist.

Slap-Happy Lion (M-G-M, 1947) has a remarkably similar set-up (see below).

(notice how blurry, fuzzy and unrestored this image from Slap-Happy Lion is! Join me in a moment of tearful silence for the horrendous treatment accorded Avery's M-G-M cartoons)

Now Robert McKimson takes over. As Devon Baxter notes:

Nice, complex angles on the heads and bodies.

Outstanding dry-brush work by the ink and paint department throughout this cartoon.

Willoughby 's vain effort is underlined by Bugs' early emergence from another rabbit hole.

Bugs is delighted. His day is made! And did he ever look better than in Robert McKimson's hands?

Bugs will not do many more of these "pixilated" zany intros.

His personality outgrew the norm for the "zany" type. Cool and calculating, Bugs was his own character archetype--one that resisted easy imitation. Being a spazzy lunatic is easy; containing those impulses and being in control of whatever situation arises takes fortitude and intelligence. In Bugs' best films, you feel his smarts. In these earlier episodes, some of that mindset is there, but he is still a work in progress, as he'd remain throughout other directors' cartoons of this decade.

This activity bears further investigation.

Bugs utters his immortal catch-phrase to get dog's attention.

Bugs is informed that "there's a rabbit down here and I'm going to catch it."

This is one of a few moments where you can hear a tinge of Rogers' forthcoming characterization for Beaky Buzzard. His version of the Lennie voice is more nasal--a trait shared in Wally Maher's persona for Screwy Squirrel, Avery's M-G-M bete noire in an attempt to make lightning strike twice.

Ever obvlivious, Willoughby checks out, after which Bugs wishes himgood luck and departs--casually and slowly. There's no need to hurry or worry.

It takes longer than Bugs anticipated.

The clods of dirt falling away is a nice touch."Dah...h-hey...

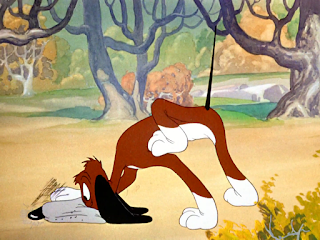

With tense anticipation, Willoughby explodes into action.

Dry-brush beauty in action.

Bugs saunters carefree, his carrot brandished like a cigar. He dips below

to evade the canine holocaust with perfect timing.

Devon Baxter: This should be displayed at the Louvre (re: frame above)

Bugs takes quick assessment of scene, then returns below.

Robert McKimson's long sequence ends; I'm not sure who drew this next shot, as Willoughby skids to a halt like a Buick roadster with braking problems. It doesn't look like Ross or Robert McKimson.

Rod Scribner takes over, and The Heckling Hare is a breakthrough film for his animation. He expresses himself and his masterful sense of contour, exaggeration and energy with manic zest.

Here, he and Avery salute a classic scene from the Marx Brothers' classic Duck Soup (1933). This much-imitated bit of business had been done long before the Marx version, and Avery finds a way to get something new into this chestnut.

Familiar stuff, and the kind of crowd-pleasing bit that could go on for another two minutes in this manner. But Bugs being Bugs, he subverts the formula and turns a tennis match into an armed duel.

Bugs drops out of the race and enjoys the show.

Avery and Stalling create a rote, mechanistic timing to the dog's movement--he's locked into a mental/physical closed loop that could go on forever. Bugs savors the greatness of this moment, then adds a silent commentary, courtesy of an Avery Sign:

Time to change this routine.

I once got good advice from a great cartoonist. I was concerned about showing a scene of violence in one of my graphic novels. His take: show what happens before and after the moment of violence. He assured me the reader would fill in the gap and spare myself and the artist the job of drawing the painful moment. Avery had already provided a great example of how to do this with this shot.

Two plain color cards, flashed subliminally, score a greater impact than that baseball bat creasing Willoughby's skull. This is highly sophisticated use of film form to make the audience sense and feel what they don't see.

Bugs administers the Kiss O' Humiliation (one of three he'll give in this picture)with attendant distortions by Scribner.

As said earlier, Bugs wouldn't indulge in this daffy-for-daffy's-sake behavior much longer.

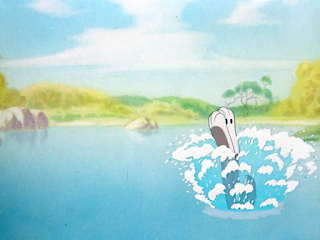

To mix things up, Avery throws his duo in the drink.

Devon Baxter notes: "This quick shot of Bugs nearly falling looks like...either Charles McKimson or Sid Sutherland. It doesn't match the drawing or timing of the other three artists, in my opinion."

I agree, Devon. These drawings are a bit off.

The next scene is Robert McKimson. In contrast to Bugs' fussy routine with his shower cap, Carl Stalling's score is frenzied and tense. The contrast works so well that it couldn't be coincidental.

This shot is a warm-up for a more trying sequence-to-come.

Bugs has great diving form.Willoughby follows with surprising grace...

...for a moment.

This set up involves a double-exposure of the water, plus grey holding lines for the parts of both characters underwater. This elegant touch was indiscernable on the faded, battered TV prints baby boomers grew up seeing.

The chase is communicated via bubbles and disturbance in the water. This diagrammatic approach will serve Avery well throughout his M-G-M period. It doesn't translate to still frames well, but the turbulence is clearly positioned and expertly timed. This is the type of gag that would later be associated with the French film comedian Jacques Tati. Both moviemakers endow static and mundane things with life and reveal the universality of it all.

A rock provides a compass for comedy.

Having impressed us with cutting-edge visual comedy, Avery trots out one of the oldest gags in the book, as he was wont to do for his own amusement.

There was no reason to get in the water, so there's no reason to stay there.

Robert McKimson returns for this next sequence.

The effects animator had an increased workload on this picture.

Stalling's underscore is a series of modernistic chords--one set for Willoughby's determined trudge, another for Bugs' Groucho-esque pacing on the dog's rigid spine. A piano figure dances atop this sludge of dense harmony.

"Le'see... what can I do to dis guy now?"

Mel Blanc brings a new level to his voicing of Bugs. His persona's cool increases as Blanc modulates the Brooklynese and gives Bugs a real sense of calm. Blanc will further perfect the voice and peak with the character in the late 1940s.

Bugs recalls a niche he can scratch.

Bugs performs this act of kindness twice, then delivers another

Kiss of Humiliation to enrage his opponent anew.

In a nice bookend to the water frolic, Bugs does a springboard dive off the dog's tail.....,and into a tree.

Next is a scene tailor-made for Rod Scribner. The gross-out scenes in later Bob Clampett cartoons have their origin here. A tell for his Bugs (if the wild poses, wrinkles and distortions aren't enough) are the reptilian/feline pupils in his eyes when they're centered in their sclera. No other animator did eyes this way, and it's part of the unique affect of his work.

There's potential here...Bugs' glee is a mite disturbing.

Offstage props are there for the asking.

Keen to his opponent's single-minded nature, Bugs revels in what will happen next.

Scribner's over-wrought reactions are priceless.

You feel for ol' Willoughby, and it's telling that we don't see Bugs' reaction in a cutaway shot. This overboiled drama is played to the hilt by Scribner; '41 audiences might have been moved for a few moments by this mournful travesty.

"I crushed him..."

Some of Kent Rogers' whoops and wails bring to mind the 1940 hit record by Bob Atcher of the Carter Family classic "I'm Thinking Tonight of My Blue Eyes." Please listen to the whole thing, but if you're impatient, skip ahead to around 2:02 and bear with it.

Virgil Ross takes over for a long shot of this spectacle of grief.

"I done a bad thing..."The above wail is purely heart-rending.

We fade out and fade in on a heartfelt memorial.

"Flowers," the dog tells us.

"Rest in peace...poor lit-tle buh-nee..."

You know this show of emotion is gonna be violated.

"For me?"

"Oh, you daaar-lin'!" Bugs camps it up...

...and delivers Kiss O' Humilitation #3.

We're not sure who the animator of this sequence might be. Educated guesses include Charles McKimson and Sid Sutherland.

Bugs accepts gift.

The cartoon now enters the territory that caused Avery's walkout.

More on this after the blow-by-blow analysis.

There's a leap of logic here. The previous shots have given no indication that Bugs and Willoughby are so near a steep cliff. This is, of course, cartoon logic*, so the settings adapt to the need of the narrative.

More impressive special effects animation.

The stunned expression following the take is funnier than the take itself.

Stalling uses a chilling, effective two-chord motif to underscore the threat of the plummet.

Virgil Ross returns with spot-on character work. With Kent Rogers' voice, it creates a remarkable moment of seemingly impromptu and well-considered choices.

Willoughby's casual connection to the audience shows how comfortable Avery was, at this point, in making the invisible wall between medium and spectator fade when needed. Rogers' performance drives this home. He reminds himself to be more careful...

...and walks off the cliff.

New animator; not sure who this is. Their work looks a little off compared to McKimson, Ross and Scribner.

Stallings' two-chord scare cue plays as Bugs watches the falling canine.

" (crunch, chew) Too bad..."

"...but the joik haddit comin' to 'im,"

"He should of watched his step."

Bugs' pitiful silhouette is seen in a brief long shot.

Misery meets company.

Why wasn't this scene given to Rod Scribner? Oh, well...

To stretch this action out, animation cycles, shifting POVs and shot re-use are rampant here.

An iconic shot.

Brakes applied, with attendant sound FX.

That's 43 seconds of falling. It took most feature films twice that time for a simple exchange of the most mundane dialogue. Under a minute of anything is bearable to most viewers.

"Nyah! Fooled ya, didn't we?"

"Yeahhhh," dog says as we abruptly fade out.

What was intended next, according to Avery's recollections, might have been part of the alleged problem. It has been subject of much conjecture, as is common with film history and in particular animation history. What is known is that, as Avery intended, the film would have prolonged the perilous plummet of its two characters by another 40 feet of celluloid. No disputing this. It's reported in two trade journals.

The legend insists that the film ended with a reference to a naughty joke that had been making its rounds since at least 1907. Gershon Legman immortalized the quip in his 1968 treatise Rationale of the Dirty Joke: An Analysis of Sexual Humor (Simon and Schuster):

It's a joke that Avery might have heard in his youth. An inveterate student of comedy, he filed away tidbits that might get a laugh in his cartoons. The story would have been known to a large percentage of the 1941 audience.

And, after some search (and the help of Devon Baxter) I have recovered a document posted by Thad Komorowski on his blog in 2011 (and since gone missing). This is my third revision of this article, as truth and fiction keep running me down on the street of history. The transcript, which you can see below, clearly shows the dirty-joke punchline occuring two times in the excised finale.

It seems pretty hard to refute this piece of evidence. It seems curious that the same bit of business happens, word for word. If this is accurate, it might have confused its audience. For a few seconds, they might've felt stuck in a time loop.

As for the disputed footage: 40 feet of film is 26 seconds. That's half the time of the prior fall. It's possible the second and third falls could have played in that time, if sped up--something Avery would do at M-G-M to achieve a frenzy of impact and expression.

My take on the event? I think Avery saw his future. Working for Schlesinger meant working with established characters--audience favorites who dominated their output. Characters can be a gift for creators. They can also be a strait-jacket. For Avery, they were the latter. Like Alfred Hitchcock, Avery was a chess player on film. Characters were mere game pieces to move on the (story)board to suit his needs. They didn't need personalities or lovable attributes.

This may have been the attraction of the Speaking of Animals concept--which feels like an idea someone might dream up during after-work drinks and be convinced is the greatest thing since sliced bread. It worked well enough for the series to run almost a decade. Avery's concept has gotten plenty of use in the digital age in children's video, commercials and television. Its appeal is long borne out. But it's no substitute for cel animation. It's a gimmick, not a way of life.

The other Schlesinger directors thrived on the studio's characters. Bob Clampett embraced Daffy Duck and Bugs Bunny, and used them as conduits for his limb-splaying, taste-affronting, in-your-face comedy style. Friz Freleng saw them as means to an end to achieve tight, controlled cause-and-effect action. Chuck Jones enjoyed getting inside the characters' heads and nurturing comedy from within. And Frank Tashlin, the most Avery-like of the group, used Daffy Duck for an uncanny forecast of Jerry Lewis' film persona.

Avery needed pawns, a playing field and stakes. From those base elements, he conjured a universe. Staying at Schlesinger meant he had to use Bugs, Daffy and the other stars. He couldn't make one-shot cartoon to his heart's content. And though M-G-M urged him to "create another Bugs Bunny," his series characters were achieved by accident. Droopy wasn't intended to be a cartoon star, but his lack of presence intrigued Avery enough to continue with him. Screwy Squirrel is the antithesis of a cartoon icon--unlikable, abrasive and confrontational. George and Junior seem closest to Avery's heart, and were ideal pawns for his comedic sense, but their relationship forced emotional stakes that their creator didn't want.

The recurring figures in his M-G-M cartoons are not automatically appealing. They're funny because of what happens to them. Their choices and actions put Avery's comedy machine into action. It doesn't matter what happens to them. They are diced, sliced, burned, mangled and shattered. The only reason for them to be there is some sentient thing had to occupy the frame so that the comedy machine would work.

By 1941, it was clear to Avery that Schlesinger was not the place to achieve this film vision. Rudderless M-G-M was ideal: big budgets, top animators and craftsmen and a producer who had no clue what he was supposed to produce. Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera's Tom and Jerry gave the studio iconic and merchandisable characters and cushioned Avery to make the films he wanted to make, and not those he felt he was obliged to. It opened up a new world for him. Thus, cartoon man walked out for the betterment of film comedy.

Thanks to Keith Scott, Thad Komorowski and Devon Baxter for their help in trying to piece together a clear account of this fascinating dramatic moment in Avery's career.

* Speaking of Cartoon Logic, Thad Komorowski and Bob Jaques have a wonderful new podcast by that name. There are four episodes to date and you can find them HERE and HERE.

Next: One Moment of Greatness--Aviation Vacation

I seem to recall a gag in some other cartoon where the protagonist survives a fall in the same manner, then turns and falls through ANOTHER hole, just to repeat the fall. Is it possible that this was the excised gag?

ReplyDeleteMaltese might have brought the opening -- or at least he might have brought it back. Aside from not liking the extended fall ending, Leon may not have been too happy with his new star riding out on the WB shield, looking at the audience and basically telling them to buzz off. The most irked part of that animation, and the curtain pull-down, disappear for the rest of Schlseinger's time at the studio, replaced by the fade to the Merrie Melodies title card, just as Bugs glance at the audience (done by doing one more cycle of his carrot chewing).

ReplyDeleteThe updated 'Annoyed Bugs' opening returns with 1945's "Hare Trigger", which Maltese wrote for Freleng, and which apparently was their first Bugs cartoon put into production after Leon sold the studio (his name's still on the lobby card for Mike and Friz's previous Bugs effort, "Hare Meets Herr"). They apparently took advantage of the new expanded artist credits to revive the Avery opening, and Bugs pretty much telling the audience the cartoon will start when he's ready for it to start really fits the character more than the "Happy Face Bugs" opening that showed up in the months just before Schlesinger sold out to Warners.

Many thanks to Devon for providing the Hollywood Reporter article. (I have been searching for that for a while.)

ReplyDeleteI find it interesting that there have been conflicting accounts as to why The Heckling Hare ending was cut and the connection (if any) to Avery's departure. Even more interesting that Avery cited a completely different reason for his departure. Could his involvement with producing the Speaking of Animals films have been a violation of his contract with Schlesinger?

I think your assessment for Avery's departure is spot on. I recall reading a Virgil Ross interview in which he said the same thing (no mention of Heckling Hare or a dispute of any kind). McKimson even later recalled that Avery didn't want to do any more Bugs shorts after A Wild Hare.

I wonder if Milt Gray's interviews with Avery can shed any additional light on that incident.

What a great analysis of a great cartoon.

ReplyDelete