6/5/1937 (according to the Big Cartoon Database; IMDb claims a 7/12/1937 release date)

DVD/BLU-RAY AVAILABILITY:

NONE

We once had access to a very nice print of this cartoon, but it was taken down. An adequate version may be seen HERE, and you can always take initiative to find other versions out there. It's easy, mac!

The first of two Avery cartoons banned from television airing by the late 1960s, Uncle Tom's Bungalow is part of a group of cartoons animation scholars (and fans) refer to as "The Censored 11."

These cartoons were suppressed mostly for racial stereotypes that were too much for post-civil rights America. Aside from prints hoarded by collectors, these cartoons were often difficult to see, pre-Internet—and are still often encountered in faded, lo-rez versions that do the originals no favors.

Arguably, only three of the "Censored 11" are great cartoons. Bob Clampett's exuberant mini-masterpiece Coal Black And De Sebben Dwarfs (1943), Friz Freleng's solid, funny musical Goldilocks and The Jivin' Bears (1944) and this Avery cartoon are the real keepers of this clandestine subset.

Appreciation of these cartoons requires the viewer's understanding of the era and circumstances in which they were made. In Avery's case, they raise larger concerns and ask bigger questions.

Fred/Tex Avery's use of racial stereotypes, throughout his cartoon career, is a can of worms any serious student of his work must open and confront. Avery's other "Censored 11" entry, 1941's All This and Rabbit Stew, is utterly abhorrent, despite touches of comedic brilliance. The same can be said for his 1948 Half-Pint Pygmy—a cartoon that has a lot going for it, has inspired set-pieces and comedic concepts, and is a pinnacle-example of lush, elaborate studio animation.

To a much lesser extent, 1947's Uncle Tom's Cabana suffers. Its fierce, relentless comedic energy is undeniable, and it has moments that are among Avery's best as a humorist and movie-maker.

Avery never, to my knowledge, publicly spoke about his racial views. Several moments—and entire cartoons—attest to an apparent disdain for African-Americans. A constant cheap-shot gag in his career is the explosion that turns a "Caucasian" character into a coal-black, drawlin' Stepin Fetchit until the fade-out.

Arguably, all cartoon characters were held in comedic contempt by Avery, especially in his brilliant M-G-M efforts of the 1940s and '50s. Just as Hitchcock considered actors "cattle"—a means to an end to fulfill his vision—Avery held little regard for the figures, good and bad, that had to occupy his film frame.

Avery sought to constantly shatter the "illusion of life," as Disney's men called it, in his cartoons. Getting a reaction from his audience, no matter how hard or how meanly he had to rattle their cages, was his prime motivation for making cartoons.

All this needs to be put on the table in order to truly appreciate any of Avery's work. The first three and a half minutes of Uncle Tom's Bungalow are significant. His earlier cartoons dabbled in the downfall of the fourth wall, through the use of intrusive narrators (one of the greatest formal innovations Avery brought to the theatrical cartoon) and character-ciphers' acknowledgment that they are just ink and paint on animation cels.

For its precious first 3:30, this cartoon implores us to be conscious that there is no fourth wall. Through use of the reactive narrator, fluid and playful embrace of modern film technique, and increasingly layered, elaborate and expressive animation, Avery delivers another major blow to the Disney approach.

The remainder of Uncle Tom's Bungalow is familiar material, with only a few touches to justify its existence. The Avery unit is on another downhill slide. Its next four cartoons are weak, problematic and/or repetitive. The remainder of the 1930s will prove tough going for Avery. There are several minor gems, and four or five outright masterpieces, among these cartoons. Too many others are forgettable, save for stray moments of inspiration.

This cartoon introduces the highly distinctive, eccentric animation of Irv Spence to the Avery unit at the Leon Schlesinger studio. Spence has three short scenes, but makes his presence boldly felt.

Spence was to Avery's cartoons what Jim Tyer was to early 1950s Terrytoons: a talented artist and animator who didn't give a fig about conforming to the style of a cartoon studio. Spence's animated scenes are dynamite--they seethe with life and energy, and each pose is pure eye-candy.

Let's savor the first sequence of this cartoon. Immediately after the title card, a peppy down-home performance of Stephen Foster's "Old Folks At Home," reminiscent of the early Mills Brothers recordings, causes the camera to bounce up and down in time to the infectious rhythm.

Attempting screenshots from this opening salvo—a long, elaborate vista of Hollywood Delta-land—is a fool's errand. I assume you've watched the cartoon before you read this essay. This is a truly disarming moment—something unseen in mainstream commercial film-making. It's a liberating effect—one still capable of startling an audience. In the late spring of 1937, it must have caused a momentary sensation in theaters.

This touch is Avery's announcement that we are out of our safety zone as spectators. All we can do is sit back and watch.

The camera trucks in on a Central Casting antebellum mansion, as a slightly cynical narrator (masking his ennui with forced cheer) welcomes us to this unsettling world. "That's real swing, boys," he says as the jolly burst of DIY music ends. "Now to introduce our characters..."

"First, the little lady. Tell us your name, honey..."

We don't expect this animated tot to talk and think like a real-life little girl. The voice artist's performance is sublime, as Little Eva babbles excitedly and believably about nothing and everything...The realistic bombard of her jabber irritates us. Avery loves riling his audience, and this includes taxing their patience. We hardly notice that the little girl has not answered the narrator's question. She proceeds to get him (and us, the passive voyeurs) in trouble...

"An' I got lace on my panties, too..."

"Ya wanna see?"

"Hey! Hold On! No no no NO!"

"Remember... you're a BIG GIRL!"

Narrator presses with the question again.

"LITTLE EVA, YOU DOPE!"

Mission accomplished, the narrator moves on to the next protagonist...

Our narrator is equally condescending to all creeds, races and colors, so no one is judged by their ethnicity—a refreshing move for this type of cartoon. Next, we meet Topsy.

Potentially cringe-making as Topsy's introduction is, one cannot deny its cleverness.Our narrator is equally condescending to all creeds, races and colors, so no one is judged by their ethnicity—a refreshing move for this type of cartoon. Next, we meet Topsy.

NARRATOR: "Hey, girly. Step out of that shadow and introduce yourself to the folks here."

"Heh heh heh—that's cute," the narrator says (not convincingly), after Topsy name-checks herself. We immediately dissolve to the title figure in our meta-story:

Narrator comments on Uncle Tom's enfeebled figure, and notes how pitifully his knees shake as he walks.

"Brother, my knees ain't shakin'—I'se truckin'," Tom replies, adopting the jive du jour. Narrator is speechless/impressed.

As her movements become more vivid, one thinks of Daffy Duck's caroms in Porky's Duck Hunt. That said, this is probably NOT Bob Clampett's animation. By this time, he was at work on his first cartoon as a unit director, Porky's Badtime Story.

For a cartoon in which nothing has yet happened, we've already seen a great deal of expressive character animation.

The verbal tic of Simon Simon Legree is quite witty. In concert with Jones' world-class animation, it's an oddly elegant moment in an irreverent piece of film-making.

FUN FILM FACT: Legree's double name is a reference to the alluring French actress Simone Simone, who had just appeared in a remake of the silent classic Seventh Heaven, and is best known today for her roles in the Val Lewton productions The Cat People and The Curse of the Cat People. Her unusual name, and the Hollywood promotional blather over her, was catnip to Avery's satirical soul. This is she:

Finally, we meet the hounds. Their inertia is its own gag.

The narrator checks back in with the major characters, in the event that one or more have changed their mind about further participation. All give an affirmative:

"You said it, soft, dark an' bow-legged!"*

"Anytime y'all say, Professuh."

"Oh, sho', sho', sho'."

"Yeah, main!"

"The sooner, the sooner."

"Yeah. I guess so. There ain't nothin' else t' do."

The remainder of Uncle Tom's Bungalow is an anti-climax, after a formal film experiment that tests our patience while it lacerates the tropes of Western storytelling. This three and a half minutes is among Avery's greatest work.

There is nothing PC about the next sequence, despite one brilliantly existential piece of dialogue. We must remind ourselves that the scene is a parody of its source material—not Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel of 1852, but the many, wildly popular stage melodramas freely adapted from that book.

Anyone who lived in the rural America of the late 19th century and early 20th saw this play, or knew someone who had. It was as embedded in the public gestalt of 1937 as Star Wars is now.

"Here we go," the narrator says, as if to warn us.

"Camera!"

The lens-eye duly trucks back, as a sinister theme and overly melodramatic evil laughter fill our ears.

Simon Simon cracks that whip.

There is a disturbing sight gag, just in case we weren't uncomfortable enough.

Our next view is a pan shot that, while valid as meta-comedy (the substitution of Negro slaves for used cars is a brutal piece of social commentary, if not an unforgivable bit of race-slurring), is a tough sight for sensitive souls. A study is a study, so...

The narrator takes the reins of the characters' destiny here, and never quite lets go. He warns the dozing Uncle Tom of his exploiter's approach.

Uncle Tom utters another uncomfortable line of meta-comedy:

"My body might belong to you..."

"...but my soul belongs..."

"...to WARNER BROTHERS!"

Tom prepares to pay for his absolute truthfulness.

Avery's treatment of this story, and its characters, would have been called camp in the 1960s. In 1937, it was burlesque, and a late example of the mockery of Victorian America that persisted in the ultra-modern vibe of the 1920s and early '30s.

Cut to Little Eva and Topsy, engaged in deliberately mindless (and obnoxious) skipping and la-la-la-ing.

Cut to Little Eva and Topsy, engaged in deliberately mindless (and obnoxious) skipping and la-la-la-ing.

Satirical signage is a guarantee that we're in Averyland.

"Stop! Stop! Stop!"

"We'll buy the nice old ma-yun!"

The next scenes are played tongue-in-cheek, but faithfully follow the hoary melodrama. Girls are warned that defaulted payment will result in repossession of Afro-American.

Protagonists skip and "la la" back home. All seems serene.

The seasons shift. "My, my! How time does fly," our narrator croons.

"Looks like bad news, folks," the narrator needlessly adds, as we return to Legree's place of business.Exactly what you expect to happens occurs here. Legree's hand is distressingly hairy.

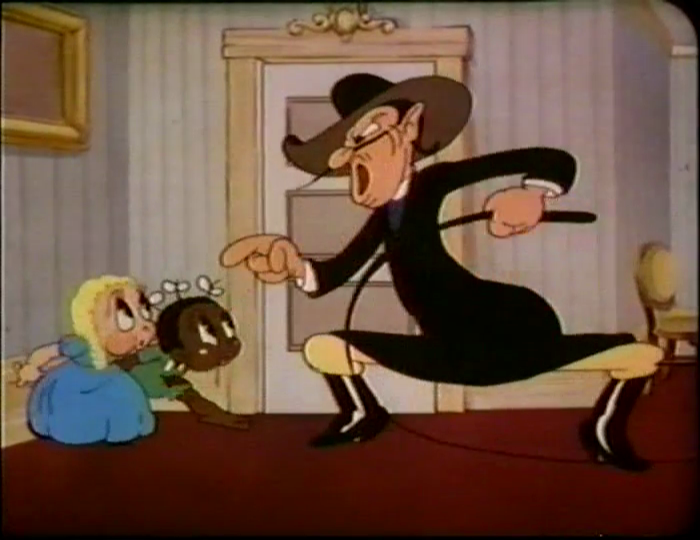

Another scene of Chuck Jones animation allows Legree some major scenery-chew.

The narrator deduces that Legree is "up to no good!"

"I'd better warn the kids!"

"Jiggers, kids! Ditch Uncle Tom! Here comes Legree!"

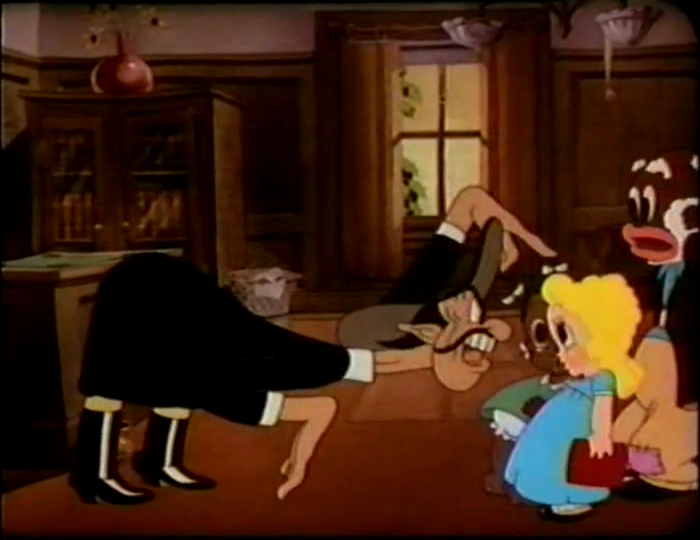

Form follows function in the architecture of comedy. The bland airbrushed Civil War portrait above the chest of drawers becomes a perfect hiding spot.Here is Irv Spence's first scene in an Avery cartoon. Avery will put him to better work in the immediate future.

Spence's sense of design and contour makes even Chuck Jones' drawings pale in comparison.

You'll recognize this bit from Milk and Money, one year earlier...

That 1936 animation runs out of usefulness, and Legree's snaky crawl continues with new drawings.

We switch to another, less graceful animator.

Again, what happens is exactly what you guess will happen. Was this electrocution gag ever funny?

Narrator makes a bad joke at Legree's expense. Villain is not amused.

More Irv Spence animation is a welcome thing.

The distortion in Spence's poses is startling.

As is this appalling (if logical) illustration of shared fear, not by Spence:

Spence returns with the last-minute entrance/rescue by Liza, who's urged on by our narrator, who suddenly compares the coming chase to the Kentucky Derby.

To quote the narrator's running commentary is prolix, so refer back to the video if you want his blow-by-blow chatter.

The hounds' laziness is again played for laughs.

Fittingly, Legree takes on canine traits. Watch that footprint in the snow...

The Griffithian cross-cut slows down once Liza reaches the riverbank.

Narrator urges Liza not to get excited. This elicits the "Excited? Who's excited? I'm not excited!" bit that had a home in the Schlesinger cartoons for years.

Narrator tips Liza to a repeat of a sight-gag Avery has used at least twice, so far in his Schlesinger career... including in his first cartoon for the studio.

Liza approves.

She uses what appears to be actual currency.

Instant ice floe!

This long shot especially evokes silent-era film-making.

Shore is reached and breached.

"And the winner--" Narrator's breathless spouting is cut short by the anachronism of a car horn.

It is, of course, the standard-model block-long Avery roadster.

Narrator informs us that Uncle Tom has "collected on his Social Security." So there was once money to be had for senior citizens in America!

Uncle Tom has done quite well by the government.

Legree disappears, without a kick to the ass, or any expected humiliation usually accorded the villain of such a piece.

"Uncle Tom! Where did you get all that money?"

Through pantomime, the truth is revealed:

There may be something wrong with these dice.

Narrator decides it's time to wrap things up.

"There you have the story of Uncle Tom's Bungalow..."

"...or have you?"

* At least, that's what I think Little Eva says here. Other guesses include "tall, dark and bow-legged" and "strong, dark and bow-legged."Narrator makes a bad joke at Legree's expense. Villain is not amused.

More Irv Spence animation is a welcome thing.

The distortion in Spence's poses is startling.

As is this appalling (if logical) illustration of shared fear, not by Spence:

Spence returns with the last-minute entrance/rescue by Liza, who's urged on by our narrator, who suddenly compares the coming chase to the Kentucky Derby.

From here on, Uncle Tom's Bungalow becomes pure meta-cartoon, with the narrator providing both ironic counterpoint and direction to its characters.

The iconic chase through the snow, and upon ice floes, is narrated as a horse race by our announcer, who can barely conceal sarcasm as he, literally, calls the shots.

Avery's love of cross-cutting rivals that of D. W. Griffith, and he used this tool well to generate comic energy.

To quote the narrator's running commentary is prolix, so refer back to the video if you want his blow-by-blow chatter.

The hounds' laziness is again played for laughs.

Fittingly, Legree takes on canine traits. Watch that footprint in the snow...

The Griffithian cross-cut slows down once Liza reaches the riverbank.

Narrator urges Liza not to get excited. This elicits the "Excited? Who's excited? I'm not excited!" bit that had a home in the Schlesinger cartoons for years.

Narrator tips Liza to a repeat of a sight-gag Avery has used at least twice, so far in his Schlesinger career... including in his first cartoon for the studio.

Liza approves.

She uses what appears to be actual currency.

Instant ice floe!

This long shot especially evokes silent-era film-making.

Shore is reached and breached.

"And the winner--" Narrator's breathless spouting is cut short by the anachronism of a car horn.

It is, of course, the standard-model block-long Avery roadster.

Narrator informs us that Uncle Tom has "collected on his Social Security." So there was once money to be had for senior citizens in America!

Uncle Tom has done quite well by the government.

Legree disappears, without a kick to the ass, or any expected humiliation usually accorded the villain of such a piece.

"Uncle Tom! Where did you get all that money?"

Through pantomime, the truth is revealed:

There may be something wrong with these dice.

Narrator decides it's time to wrap things up.

"There you have the story of Uncle Tom's Bungalow..."

"...or have you?"

Uncle Tom's Bungalow never quite recovers from the brilliance of its opening. Its accelerated chase scenes show Avery hard at work to perfect his trademark comic timing. Avery and his animators seem comfortable in their work here. Unfortunately, they won't get another chance to break new ground for several months and four more films.

Compared to two genuinely unpleasant "Censored 11" items, Friz Freleng's Jungle Jitters (1938) and Chuck Jones' ghastly Angel Puss (1944), this cartoon seems almost tasteful. Uncle Tom has literally no personality, and surprisingly little on-screen time. Liza and Topsy are far more active and personable.

The cartoon's attitude toward its black characters is often patronizing—the narrator's referral to Liza as the "dark horse" in the chase scene/horse race mash-up is a really cheap shot. The business with the dice, at the cartoon's close, also edges into un-comfy territory. Many other Hollywood (and New York) cartoons did far worse with similar material.

Avery was conscious of the growing acceleration he pioneered in cartoons. In 1937 and '38, he received constant challenges from the Frank Tashlin unit, as it strove for super-modern high speed cutting and pacing.

Tashlin arguably out-paced Avery in his 1937 cartoons. He was the other resident genius at the Schlesinger studio, and his work and Avery's influenced—and spurred on—one another. The work both men did in the late 1930s set a standard for rapid cutting, motion and comedy that would never entirely leave the Warner Brothers cartoons.

Avery will, ironically, slow down—and become earthbound—in his next four cartoons, which include the last black-and-white picture he will make until 1941. When he regains his bearings, he will embark on a remarkable series of films that show his growing mastery of moviemaking, comedy and experimentation.

NEXT: Enter Egghead.

The cartoon's attitude toward its black characters is often patronizing—the narrator's referral to Liza as the "dark horse" in the chase scene/horse race mash-up is a really cheap shot. The business with the dice, at the cartoon's close, also edges into un-comfy territory. Many other Hollywood (and New York) cartoons did far worse with similar material.

Avery was conscious of the growing acceleration he pioneered in cartoons. In 1937 and '38, he received constant challenges from the Frank Tashlin unit, as it strove for super-modern high speed cutting and pacing.

Tashlin arguably out-paced Avery in his 1937 cartoons. He was the other resident genius at the Schlesinger studio, and his work and Avery's influenced—and spurred on—one another. The work both men did in the late 1930s set a standard for rapid cutting, motion and comedy that would never entirely leave the Warner Brothers cartoons.

Avery will, ironically, slow down—and become earthbound—in his next four cartoons, which include the last black-and-white picture he will make until 1941. When he regains his bearings, he will embark on a remarkable series of films that show his growing mastery of moviemaking, comedy and experimentation.

NEXT: Enter Egghead.

________________

PS: For a fascinating example of how other animation studios were, erm, inspired by Avery's work, check out this crappy-looking copy of a fascinating 1944 "Mighty Mouse" cartoon, Eliza on the Ice, HERE.

There is still a bit of an earthbound feel to this cartoon, even as it brings into play the idea of making fun of familiar source material (Avery did that a bit at the start of "The Village Smithy", but abandoned that once Porky entered the story).

ReplyDeleteThere also may have been a bit of lingering feeling that you had to be a little more 'formal' in a color Merrie Melodie, but with Clampett getting his own B&W unit, Tex was facing the prospect of having no other outlet for his comedy but the color Merrie Melodies. The series would start benefiting from that forced choice shortly.