Release date: 3/15/1941

Available on Looney Tunes Golden Collection Vol. 2 (WHV DVD); Looney Tunes Platinum Collection, Vol. 2 (WHV BR)

You may download a copy of the cartoon HERE.

<><><><>

The second Bugs Bunny cartoon under the Avery aegis, Tortoise Beats Hare adds another influential ripple to animation: the notion that the hero can be a loser. Or, more precisely. that the protagonist (who is also an antagonist) is prone to a different outcome than we're used to in conventional storytelling. It furthers the strong impression that Bugs Bunny is a compelling individual.

Another animation historian noted (and I paraphrase) that Bugs is the one animated character most of us would enjoy hanging out with. He is smart, world-wise, has a great sense of humor and never wants for amusement in life. If he heckles his adversaries, it's more to enlighten them of their lack of self-awareness and smarts. Bugs could be doing anything, but since he's a cartoon animal, he makes do with the options of this painted and penciled world, and enjoys his existence. Mickey Mouse is a cipher; Bugs has a genuine personality.

Characters such as Donald Duck and Andy Panda had frustration scenarios built into their series. Donald's screen persona is wholly based on vexing outcomes to simple tasks and the aggravation this brings him. But neither character is one you'd care to pal around with. (Andy Panda's passive-aggressive hostility might be a bit much to contend with for long.)

This winner-as-loser concept could be misused, as in the Famous Studios Popeye short Wood Peckin' (1943), which shows how tiresome this routine can become if not handled with finesse. The Warners cartoon directors and writers learned that Bugs had to maintain his cool and shrug off events that would ruffle other animated characters. He could not be another limb-flailing kook. Once they understood that basic truth, Bugs' character became the unflustered being we recognize as the "classic" version.

Other Schlesinger studio directors would further Bugs' persona through the 1940s, in alliance with Mel Blanc's voicing, which defines the character alongside his personality traits. The Bugs of this film is still larval. He looks less like the Bugs we know and love than in his prior film A Wild Hare. Some of the animation here looks like character designs from the Friz Freleng unit (who created a nadir of the early character in Hiawatha's Rabbit Hunt later in this year).

Tortoise Beats Hare has one of Avery's most alarming and innovative openings. Still-frame captures can't do it justice. Its effect is a culmination of Avery's direction, Carl Stallings' musical score, Mel Blanc's vocal and the combined might of the animation, ink and paint and background departments. The effect remains shocking and fresh. Avery returned to this set-up in his M-G-M cartoons, but the shock of the new renders this maiden voyage the best of them all.

Bugs struts stage-left into the title frame. Chewing on his characteristic carrot, he almost doesn't notice the credits.

He reads them with some difficulty. Charles McKimson's last name is given a heavy emphasis on the first syllable...

Not much can be done to twist Carl Stalling's name, so Bugs stutters...

"Dave...Mah-NAH-han," Blanc/Bugs intones with much more Bronx patois than he'll have in future...

"Fred Uh-VERY" is the supervisor. Old friends of this blog will recall its ungainly original logo which was derived from this scene.

There's nothing to do but remove the evidence, which Bugs does to jarring and revolutionary effect.

It's heartening to see this uptick in speed, after the sluggish years of the late 1930s (when the weight of the elaborate animation slowed Avery's progress as the cartoons developed a more appealing look).

Devon Baxter attributes this scene's animation to Virgil Ross.

Bugs gets more invasive and, in the type of behavior he'll soon lose, goes way overboard. The iconic cool of his late '40s persona is a work in progress.

"Cecil" delivers the emasculating full-on kiss that Bugs used on Elmer Fudd in his first cartoon, A Wild Hare. It's fascinating to see Avery turn this trick on the trickster. Avery's version of Bugs is a changeable creature whose success is not always easily forecast.

Bugs' exhausted gloating also inspires a stellar vocal performance by Mel Blanc. His gasping, spent delivery completes the illusion that we're witnessing physical exhaustion and glee bordering on delirium.

Baffled, furious, denied his due irrevocably, Bugs reaches in to strangle his opponent. Devon Baxter IDs this as Virgil Ross' animation.

Anger segues to bewilderment. How could this inert reptile possibly have bested him, of all rabbits?

Another animation historian noted (and I paraphrase) that Bugs is the one animated character most of us would enjoy hanging out with. He is smart, world-wise, has a great sense of humor and never wants for amusement in life. If he heckles his adversaries, it's more to enlighten them of their lack of self-awareness and smarts. Bugs could be doing anything, but since he's a cartoon animal, he makes do with the options of this painted and penciled world, and enjoys his existence. Mickey Mouse is a cipher; Bugs has a genuine personality.

Characters such as Donald Duck and Andy Panda had frustration scenarios built into their series. Donald's screen persona is wholly based on vexing outcomes to simple tasks and the aggravation this brings him. But neither character is one you'd care to pal around with. (Andy Panda's passive-aggressive hostility might be a bit much to contend with for long.)

This winner-as-loser concept could be misused, as in the Famous Studios Popeye short Wood Peckin' (1943), which shows how tiresome this routine can become if not handled with finesse. The Warners cartoon directors and writers learned that Bugs had to maintain his cool and shrug off events that would ruffle other animated characters. He could not be another limb-flailing kook. Once they understood that basic truth, Bugs' character became the unflustered being we recognize as the "classic" version.

Other Schlesinger studio directors would further Bugs' persona through the 1940s, in alliance with Mel Blanc's voicing, which defines the character alongside his personality traits. The Bugs of this film is still larval. He looks less like the Bugs we know and love than in his prior film A Wild Hare. Some of the animation here looks like character designs from the Friz Freleng unit (who created a nadir of the early character in Hiawatha's Rabbit Hunt later in this year).

Tortoise Beats Hare has one of Avery's most alarming and innovative openings. Still-frame captures can't do it justice. Its effect is a culmination of Avery's direction, Carl Stallings' musical score, Mel Blanc's vocal and the combined might of the animation, ink and paint and background departments. The effect remains shocking and fresh. Avery returned to this set-up in his M-G-M cartoons, but the shock of the new renders this maiden voyage the best of them all.

Bugs struts stage-left into the title frame. Chewing on his characteristic carrot, he almost doesn't notice the credits.

He reads them with some difficulty. Charles McKimson's last name is given a heavy emphasis on the first syllable...

Not much can be done to twist Carl Stalling's name, so Bugs stutters...

"Dave...Mah-NAH-han," Blanc/Bugs intones with much more Bronx patois than he'll have in future...

"Fred Uh-VERY" is the supervisor. Old friends of this blog will recall its ungainly original logo which was derived from this scene.

Then Bugs notices the title, hanging above him and portending his near-future...

A carrot spit-take gives way to outrage and bluster.

Bugs' grousing halts for a Groucho Marx-esque aside: "I otta know; I woik for 'em."There's nothing to do but remove the evidence, which Bugs does to jarring and revolutionary effect.

Credits creamed, Bugs intends to reverse this cartoon's agenda. The wake of this moment will be felt in all cartoon studios. The first responder was Famous Studios, who did a brilliant variation on this idea in the Dan Gordon-directed Popeye cartoon The Hungry Goat (1943).

What's surprising, in retrospect, is that no other director of Warner Brothers cartoons attempted any shenanigans along these lines. Perhaps it was felt this was Avery's provenance, as he continued to work it over at M-G-M through the 1940s. Friz Freleng and Chuck Jones developed their approach to audience/character interaction; at best, theirs was more casual and inclusive in nature. This off-handed, hip awareness of the film/spectator contract turns a throwaway moment into a major event that remains bracing decades later.

What's surprising, in retrospect, is that no other director of Warner Brothers cartoons attempted any shenanigans along these lines. Perhaps it was felt this was Avery's provenance, as he continued to work it over at M-G-M through the 1940s. Friz Freleng and Chuck Jones developed their approach to audience/character interaction; at best, theirs was more casual and inclusive in nature. This off-handed, hip awareness of the film/spectator contract turns a throwaway moment into a major event that remains bracing decades later.

A number of woodland bungalows-in-trees are investigated until the right one is found.

In the wake of that stunning act of vandalism, Avery shows an increased pace, as what might have eaten up 20 seconds in 1939 becomes a glance and a blur.It's heartening to see this uptick in speed, after the sluggish years of the late 1930s (when the weight of the elaborate animation slowed Avery's progress as the cartoons developed a more appealing look).

Devon Baxter attributes this scene's animation to Virgil Ross.

Bugs lapses into a reprise of the Big Bad Wolf's immortal lines about huffing, puffing and the removal of lodgings. He stops, apologizes with a sheepish grin, and continues.

I wish I'd known about the MPC-HC Media Player years ago. I'm able to get wonderful moments in the animation that VLC Media Player couldn't catch.

Bugs looks a bit Freleng-ish in this pose.

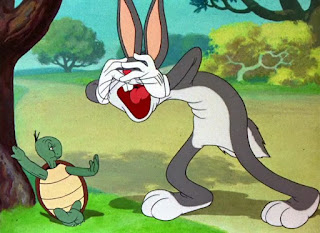

After much ado, Bugs confronts Cecil Turtle. The distortions and fleshy folds of animator Rod Scriber are evident in this scene.

Cecil Turtle offers a bucolic "uh... hel-lo."

Bugs has poor boundary issues this early in his career. He prods, provokes, shakes, rattles and de-shells Cecil in his indignation.

"Uh... yes..." is Cecil's reply to Bugs' if-you-think-you-can-beat-me... raving.

Bugs gets more invasive and, in the type of behavior he'll soon lose, goes way overboard. The iconic cool of his late '40s persona is a work in progress.

"No" is not a word Bugs is used to hearing.

Bugs's body makes a 100% unintentional swastika shape (it becomes more extreme than the example below). A pose is just a pose, but the swastika-moment always catches my eye when I see this cartoon.

A $10.00 wager is made and mutually agreed upon...

...and the first act of the cartoon dissolves into the start of the second. The Hydra-headed composite Bugs tells all about his cocky, dismissive attitude towards the race. For one of the few times in his long career, he will eat crow.

Bugs pretends to follow the rules.

Cecil acknowledges readiness.

You just know Bugs will take off prematurely, but the poses are dynamite.

Cecil's utter lack of speed inspires a toddling theme by Carl Stalling.

In medium shot, Cecil pauses. Amusement and delight play on his face.

He turns his shell on us and walks (at no greater speed than his run) away...

This could be the background painting for a Screwy Squirrel cartoon. The Avery look-and-feel of the 1940s has arrived.

Avery adored this joke, as did other cartoon-makers. It got a laugh once, I'd wager.

But with that stale jape, the fun begins.

Devon Baxter: This looks like Bob McKimson--very tight and controlled.

There's no doubt the split-screen device will be violated.

Avery has leaned on this bit of business many times in the past.

A montage sequence, like those Don Siegel created for Warners' live-action features, gives us lots of hot turtles-on-telephones action as a plan is hatched and instigated.

A turtle (which may or may not be Cecil) waits to set the plan into slo-mo action.

Bugs is about to get brain-fudged.

"Cecil" offers pleasant greetings in passing; calls Bugs "Speedy."

In Averyland, such nicknames are steeped in sarcasm.

Then, in a brilliantly timed moment, Bugs freezes.

You can see Avery's drawing style in Bugs' bamboozled expression.

Bugs would evolve into a personality that never did extreme takes. It was part of his agenda to never surrender his cool. The few outright shock-takes in his filmography happen early. Bob Clampett's gangly, aggressive Bugs turned the tide away from the typical take as seen below, which became Avery's specialty as they became wilder and weirder through the decade. Clampett's Bugs has broad reactions to surprise events, but in Clampett's wake, he never breaks a sweat, although he may get miffed, rebellious or indignant.

To Virgil Ross' fine animation, Bugs does a marvelous who-what-how routine as his brain

attempts to sync with what appears to be reality.

Sweaty, even!

Confusion gives way to anger. How, Bugs asks, could this turtle outpace him?

Turtle's answer, "Juuust....runnin'," is a triumph of subtlety for Mel Blanc.

Anger, confusion, physical assault: turtle is de-shelled...

...and Bugs attempts to regain the lead.

But this breach of prowess really bothers him. He skids to a halt and discusses his confusion with us. This gorgeously nuanced character animation, which appears to be Virgil Ross' handiwork, could go on for an hour. It ends with one of Avery's finest pieces of comic hair-trigger timing:

The choreography of Bugs' pointing gesture and the arrival of "Cecil" is breathlessly quick and achieved with perfection."Cecil" delivers the emasculating full-on kiss that Bugs used on Elmer Fudd in his first cartoon, A Wild Hare. It's fascinating to see Avery turn this trick on the trickster. Avery's version of Bugs is a changeable creature whose success is not always easily forecast.

Bugs bounds up another grade and stops to taunt his opponent from afar.

In a split-second whip-pan, "Cecil" is revealed to be far ahead of Bugs...

...which occasions another "takem."

"Cecil"'s lope is eclipsed by Bugs' blur.

Turtle is unfazed. He offers another Avery bromide:

We do this kinda stuff to him all through the picture.

Bugs finishes an ad hoc blockade.

Congratulates self on clever effort.

"Cecil" agrees. Bugs admires turtle's good taste, gets all brotherly...

...and loses an eyebrow for a moment.

The nickel drops; another kiss of shame is administered.

Bugs does a long, shuddering take...

...and exits stage right in a cut so fast the eye doesn't see it.

The bridge is on a cel, so you know Bugs is gonna cut the ropes.

You don't get to see this terrible drawing of Bugs (above) unless you can grab a still frame like this.

Bugs hugs a tree; shimmies up for a better view.

#StrangeBugsView

The predestination of Avery's world means we know "Cecil" will be up the tree above Bugs.

Yep.

Smooch o' humiliation #3.

How much more can one rabbit take? We still have 90 seconds to go.

Some of that time is eaten up with a series of shots of Bugs running his cotton tail off.

Dissolves and jump cuts fortify the life-or-death hurtle of this movement.

Bugs lunges for the finish line.

We get a reprise of the subtler side of Robert McKimson's animation. Bug's exhaustion and his shortness of breath are palpable. As in the death scene of A Wild Hare, McKimson brings gravity and believability to a moment that didn't have to have it.Bugs' exhausted gloating also inspires a stellar vocal performance by Mel Blanc. His gasping, spent delivery completes the illusion that we're witnessing physical exhaustion and glee bordering on delirium.

The voice of the turtle rains on Bugs' parade.

Uh...hey, uh...Speedy. What...uh...kept ya?

Baffled, furious, denied his due irrevocably, Bugs reaches in to strangle his opponent. Devon Baxter IDs this as Virgil Ross' animation.

Anger segues to bewilderment. How could this inert reptile possibly have bested him, of all rabbits?

"Cecil" adopts Bugs' iconic leaning, crossed-legs pose as he listens and waits his turn.

Turtle demands bet payment. Cut to an animator we can't quite place.

Devon thinks it might be Sid Sutherland. There are characteristics of Rod Scribner's work in this scene, including flailing limbs, skin folds and exaggerated poses. Yet it doesn't quite match Scribner's work in general, unless this was a sedate effort.

Sore loser Bugs amuses "Cecil" with a useless but delightfully drawn nyah-nyah.

Shifty, embittered, completely at sea, Bugs agonizes over the aftermath of the race...

"Hey...

"I wonder if I been tricked..."

The turtles, as one, close the cartoon with the WB catchphrase "Nyeh... it's a possibility..."

...and a group kiss-assault that sends Bugs off-frame...

...and ends with an atypical fade to black, rather than the iris so

common to Schlesinger cartoons of the day.

Avery and his storymen were inspired with Tortoise Beats Hare. When compared to later episodes in the Bugs series, it may seem too unusual for comfort. But that's the point here. A Wild Hare established Bugs Bunny as the trickster/wiseacre/outsider he would be for the rest of his days as a theatrical animation star. This film showed that Bugs was believably flawed. He has shortcomings (egotism, a quick temper, arrogance) that, while unbecoming in a president, are rich material for a cartoon character.

Bugs wouldn't perfect his cool-calm-collected routine until Bob Clampett was done with him. By the dawn of the 1950s, that persona was such a part of him that any acts of surprise seem alien. The Bugs of Chuck Jones and Friz Freleng's best cartoons maintains his superiority by never losing it. His classic encounters with Freleng's Yosemite Sam work (in part) because Bugs never reacts as Sam wants him to. Sam digs his own grave by taking the bait and giving the reaction that Bugs won't have.

In Chuck Jones' Rabbit of Seville, Homeless Hare and the '50s hunting trilogy, Bugs shows amusement and righteous anger. Never does he register genuine fear or panic. We like him for many reasons, but his unflappability is high on the list.

Thus, it's fascinating to see Bugs show reactions and emotions we don't connect with him. Bugs may feign distress, but it's because he knows his adversaries are too dim to see that he's pulling their legs. He parodies fear and panic to further provoke his antagonists into humiliation and failure.

In two sequels to this cartoon, Tortoise Wins by a Hare (1944) and Rabbit Transit ('47), directors Clampett and Freleng continue the Bugs-as-loser motif, but their treatment reflects where Bugs' persona was at when the cartoons were created. To view these cartoons back-to-back provides a quick study of how solidly Bugs Bunny's personality coalesced within half a decade.

As a chaser, watch this 1946 Terrytoon, suggested by Thad Komorowski, but then you'll have to watch another, better cartoon just to shake the dust out of your brain.

UP NEXT: Black and white meta-brilliance with Porky's Preview.

On the Bugs of the 1950s, Franl, what is your take on Robert McKimson, oir..MACK kimson..

ReplyDeleteMcKimson's Bugs strikes me as a continuation of Clampett's Bugs. He is calmed down, in comparison, but has the excitability and mischief of the Clampett model. McKimson's is the only post-war Bugs to still do takes and react to events. At his best, as in the classic encounter with Pete Puma, RABBIT'S KIN, McBugs is a winning, engaging fellow with a lot of charm. McKimson's Bugs is the meanest of the three post-war models (can't really count Art Davis since there's just one cartoon he directed). As the WB cartoons become more mechanical and rote, McBugs begins to suffer. But the first six years of McKimson's Bugs is consistently solid, and his unit's appealing "fat Bugs" look of the late '40s is classic.

ReplyDeleteI think it was Bob McKimson who noted in an interview that the studio was surprised by the rabbit's huge success and unsure of how to keep coming up with stories for such a confident character, because audiences normally don't like someone with such a cocky personality. And you kind of see that not just here, but in Freleng and Jones' initial cartoons with Avery's version of Bugs. "Hiawatha's Rabbit Hunt" and "Hold the Lion, Please" both end with Bugs getting his comeuppance (even CLampett's first effort with the rabbit ends with Bugs in jail, though we know he's there only to torment Elmer some more).

ReplyDeleteThe idea that the super-confident guy has to be taken down a peg or two seems to drive the story here, though the first two minutes to set it up are so brilliant it softens the blow of Bugs-as-dumb-patsy the rest of the way.

(Aside from the two follow-up cartoons with Cecil, Freleng and Warren Foster would try the Bugs-as-patsy story line a couple of times in the mid-1950s, with "Hare Brush" and "Hyde and Hare". To me both have some decent gags, but they aren't as good as Avery's opening here, and the ends have that similar feel of this isn't what you came to see. Tex at least had the excuse he was treading new ground, as they figured out the rabbit's personality and what kind of opponent played against him the best.)