DVD-Blu-Ray Availability: none

<><><><><><><><><><>

A big thank-you to Devon Baxter, Cartoon Research columnist and budding film restoration person, who kept on me to finally get this post, started far too long ago, finished. His comments pepper this look at a troubled production.

1941 begins with the Avery unit's first black and white cartoon since 1937's Porky's Garden. In this period, all of Leon Schlesinger's directors took turns making monochrome Looney Tunes.

This was apparently to help the studio meet its release requirements for the year. As well, less Technicolor footage lowered the outlay of money. Most of these '41 cartoons are in the public domain. When they came up for copyright renewal, the powers-that-were possibly passed on the trouble. What could black and white cartoons do for them in the late 1960s?

There are some fine cartoons in this batch. Friz Freleng helmed some high-quality Porky Pig episodes. As my friend Thad K. has noted, they're substantially better than the late black and whites of Bob Clampett, who let Porky become a mindless figurehead. Freleng's black and whites are highly amusing and well-made.

These would be the only black-and-white cartoons of Chuck Jones' directorial career. He made a few outstanding Looney Tunes, including Joe Glow the Firefly and some Porkys. Avery served a hitch in the Looney Tunes trenches, and had been away from the series since 1937. His two B&W shorts of '41 gave us the transcendental Porky's Preview and this beautifully animated, problematic one-shot.

The Haunted Mouse is a failure as a cartoon; a fatal flaw in its storyline, plus unsympathetic characters, leads nowhere. This isn't the first time Avery has made do with a sub-par storyline. It's a surprise to see Michael Maltese's name as storyman. His scenarios for Friz Freleng and Chuck Jones are among the most solid of the mature-period WB cartoons. Maltese's scenarios are usually bullet-proof. This cartoon seems like an experiment--doing something without insurance of its success. Such risks could be better taken in a lower-budget black and white cartoon.

Cancer treatment and this guy (at left) have kept me pre-occupied. I'm in the middle of restoring Cecil Jensen's classic absurdist comic strip Elmo, which I intend to self-publish by the end of this year.

I am on the home-stretch of this blog project. It makes sense to finish it. When I decided to examine each one of Tex Avery's Warner Brothers cartoons--to establish some kind of critical exploration of a neglected and mis-judged body of films--I knew there would be some rough going. It's more pleasurable to write about films I admire and consider successful. But we learn from mistakes--our own and others'--and there is value in examining why something doesn't work.

With the sound off, The Haunted Mouse is a thing of beauty. Lush, atmospheric backgrounds and nuanced animation from such talents as Robert McKimson, Virgil Ross and Rod Scribner are state-of-the-art 1940 work. We do miss Carl Stalling's moody score if we omit the audio track--an essential component of these cartoons.

We'll go through it with sight and sound, warts and all. Ready?

As Avery will do in later cartoons like Who Killed Who? (1943) and The Cuckoo Clock (1950), a mock-mysterious motif--in this case, howling wind SFX with no music--might lead the gullible to expect something sinister. It also looks back to early sound cartoons like The Cuckoo Murder Case and Spooks (both 1930). We open on a scene of existential misery:

This multiplane shot halts with the first of several Avery Signs in this cartoon. Our feline traveler takes note:

After an eternity of "Oh, boys," the cat gets to the heart of the matter: "FOOD!"

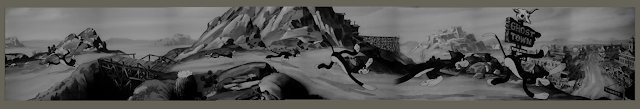

He gets ready, as if for an Olympic event, and galumphs across the forlorn vista in a manner like Willoughby the dog in the previous cartoon, Of Fox and Hounds. The ambitious background is magnificent, so I'll try to piece the journey into a panorama:

These gags are funny on their own merit--the laff-highlight of the cartoon, which isn't saying much. The shorthand atmosphere of these stills effectively tells us where we're at, while amusing/annoying us.

After this gag trifecta, a fourth sign delivers the goods:

This is what our kitty protagonist has been waitin' for. He's not the sharpest tool in the shed, so it takes him awhile to catch on to what we automatically know. This was apparently comedy gold to Avery. Via the high-functioning animation, it is funny:

Beautiful character animation in this close-up. I like the attempt to make the eyes look feline.

Devon: In watching HAUNTED MOUSE, it seems like they were trying to replicate the "heckler" archetype that worked successfully with Bugs, but doesn't come across so well here, since the heckling in question is unwarranted.

Word. This storyline is a clear case of trial and error. Audiences seemed to like the set-up of a wise-guy character who antagonizes a bigger, dumber figure. But what worked so beautifully in A Wild Hare and Of Fox and Hounds palls here. It's a mis-judgment that somebody had to make in the evolution of the Hollywood cartoon. We can forgive this failure, but it makes the remainder of this cartoon rough going.

The fatal flaw here is that the nameless cat has no prior dealings with this ex-mouse. This reductivist thinking has, historically, led to poor decisions and caused genocide, apartheid, concentration camps and such. I know this is "just a cartoon," but this animated mouse's mindset is off-putting. The Robert McKimson animation of the mouse is not off-putting.

Mouse disappears; we hear bottle opening, liquid pouring. To a jaunty "Ain't We Got Fun," mouse double-bounce steps with saucer of milk. (And here's another cartoon physics thing: our acceptance that intangible spirits can handle and transport earthly objects. I guess if you can give a guy a hot-foot underwater, as in a Famous Studios Blackie Lamb cartoon, anything's possible.)

Mouse does crossed-arm thing as he slams cat's "hood" shut. Is convinced feline needs nourishment.

It's one of the film's few genuinely funny moments because it doesn't require the mouse to be lethal towards the cat.

Now we get into Herman and Katnip territory. This is just plain painful to witness.

Ahhh... now it's hot-foot time. Let's see if it's done any faster than in our prior subject, Of Fox and Hounds...

The mouse's contempt for the cat is shown by his striking the match on the poor critter's tookus.

Devon: Some inspiration here--the cat's look to the audience before his imminent pain.

Some prints of this public-domain cartoon are mighty hard to suss out at this point. Those transparent ghosts against a light sky tend to disappear.

1941 begins with the Avery unit's first black and white cartoon since 1937's Porky's Garden. In this period, all of Leon Schlesinger's directors took turns making monochrome Looney Tunes.

This was apparently to help the studio meet its release requirements for the year. As well, less Technicolor footage lowered the outlay of money. Most of these '41 cartoons are in the public domain. When they came up for copyright renewal, the powers-that-were possibly passed on the trouble. What could black and white cartoons do for them in the late 1960s?

There are some fine cartoons in this batch. Friz Freleng helmed some high-quality Porky Pig episodes. As my friend Thad K. has noted, they're substantially better than the late black and whites of Bob Clampett, who let Porky become a mindless figurehead. Freleng's black and whites are highly amusing and well-made.

These would be the only black-and-white cartoons of Chuck Jones' directorial career. He made a few outstanding Looney Tunes, including Joe Glow the Firefly and some Porkys. Avery served a hitch in the Looney Tunes trenches, and had been away from the series since 1937. His two B&W shorts of '41 gave us the transcendental Porky's Preview and this beautifully animated, problematic one-shot.

The Haunted Mouse is a failure as a cartoon; a fatal flaw in its storyline, plus unsympathetic characters, leads nowhere. This isn't the first time Avery has made do with a sub-par storyline. It's a surprise to see Michael Maltese's name as storyman. His scenarios for Friz Freleng and Chuck Jones are among the most solid of the mature-period WB cartoons. Maltese's scenarios are usually bullet-proof. This cartoon seems like an experiment--doing something without insurance of its success. Such risks could be better taken in a lower-budget black and white cartoon.

Cancer treatment and this guy (at left) have kept me pre-occupied. I'm in the middle of restoring Cecil Jensen's classic absurdist comic strip Elmo, which I intend to self-publish by the end of this year.

I am on the home-stretch of this blog project. It makes sense to finish it. When I decided to examine each one of Tex Avery's Warner Brothers cartoons--to establish some kind of critical exploration of a neglected and mis-judged body of films--I knew there would be some rough going. It's more pleasurable to write about films I admire and consider successful. But we learn from mistakes--our own and others'--and there is value in examining why something doesn't work.

With the sound off, The Haunted Mouse is a thing of beauty. Lush, atmospheric backgrounds and nuanced animation from such talents as Robert McKimson, Virgil Ross and Rod Scribner are state-of-the-art 1940 work. We do miss Carl Stalling's moody score if we omit the audio track--an essential component of these cartoons.

We'll go through it with sight and sound, warts and all. Ready?

As Avery will do in later cartoons like Who Killed Who? (1943) and The Cuckoo Clock (1950), a mock-mysterious motif--in this case, howling wind SFX with no music--might lead the gullible to expect something sinister. It also looks back to early sound cartoons like The Cuckoo Murder Case and Spooks (both 1930). We open on a scene of existential misery:

This multiplane shot halts with the first of several Avery Signs in this cartoon. Our feline traveler takes note:

After an eternity of "Oh, boys," the cat gets to the heart of the matter: "FOOD!"

He gets ready, as if for an Olympic event, and galumphs across the forlorn vista in a manner like Willoughby the dog in the previous cartoon, Of Fox and Hounds. The ambitious background is magnificent, so I'll try to piece the journey into a panorama:

(done by hand; Photoshop's auto-align feature kept wanting to bend the perspective)

It slowly dawns on the cat that there's something off about this town. In a flurry of inserts that feels like something from the Don Siegel montage unit at Warners, gag signs inform us that there ain't nobody here:

Devon Baxter: Okay, these puns can go a couple ways: an amused chuckle, a loud groan or a derisive, haughty snort.These gags are funny on their own merit--the laff-highlight of the cartoon, which isn't saying much. The shorthand atmosphere of these stills effectively tells us where we're at, while amusing/annoying us.

After this gag trifecta, a fourth sign delivers the goods:

This is what our kitty protagonist has been waitin' for. He's not the sharpest tool in the shed, so it takes him awhile to catch on to what we automatically know. This was apparently comedy gold to Avery. Via the high-functioning animation, it is funny:

Beautiful character animation in this close-up. I like the attempt to make the eyes look feline.

And here's where our troubles begin. With this mouse-hole (the broom is innocent).

Ghost mouse emerges from hole.

Sees cat; does take.

Carries chip on his shoulder beyond the grave:

"Y'know, those guys usta run me ragged! Now it's my turn t' have some fun!"

Devon: In watching HAUNTED MOUSE, it seems like they were trying to replicate the "heckler" archetype that worked successfully with Bugs, but doesn't come across so well here, since the heckling in question is unwarranted.

Word. This storyline is a clear case of trial and error. Audiences seemed to like the set-up of a wise-guy character who antagonizes a bigger, dumber figure. But what worked so beautifully in A Wild Hare and Of Fox and Hounds palls here. It's a mis-judgment that somebody had to make in the evolution of the Hollywood cartoon. We can forgive this failure, but it makes the remainder of this cartoon rough going.

The fatal flaw here is that the nameless cat has no prior dealings with this ex-mouse. This reductivist thinking has, historically, led to poor decisions and caused genocide, apartheid, concentration camps and such. I know this is "just a cartoon," but this animated mouse's mindset is off-putting. The Robert McKimson animation of the mouse is not off-putting.

Mouse disappears; we hear bottle opening, liquid pouring. To a jaunty "Ain't We Got Fun," mouse double-bounce steps with saucer of milk. (And here's another cartoon physics thing: our acceptance that intangible spirits can handle and transport earthly objects. I guess if you can give a guy a hot-foot underwater, as in a Famous Studios Blackie Lamb cartoon, anything's possible.)

Gift horse!

As we are now so close to Avery's transition to M-G-M, it's interesting to note the visual similarities of his early cartoons for that spendier studio. The first film he completed, The Early Bird Dood It (and the second released, with the topical Blitz Wolf taking precedence) has a stupid cat among its cast. The early Avery M-G-Ms show less of his cartooning style than the late Warners, so this is Avery's work filtered through the hands of more skilled artisans:

The last image here really shows Avery's hand. It is always most evident when characters are in profile.

Avery seems overly cautious in his new home--the cocky attitude that makes Haunted Mouse a snappier cartoon is timid, as if he was afraid to get the carpets dirty or spill his coffee on the desktop. But that's another topic for another time. Back to today's subject.

Devon: Missed opportunity after the container of milk disappears: splinters on the famished feline's tongue. (Or is that me spoiling myself?)

Mouse materializes via spectral SFX that happen so fast I couldn't nab a screen-shot...

Fun fact: Mouse is voiced by Walter Tetley, best-known as the voice for Walter Lantz's Andy Panda. and Sherman on the Mr. Peabody and Sherman segments of the Bullwinkle Show. A specialist in child voices, he appeared on such golden age radio shows as The Great Gildersleeve and voiced Felix the Cat for the short-lived Van Beuren cartoon series of the mid-1930s. Tetley's performance here exudes anger and contempt. Perhaps he played the part too well, but his voicing can be seen as part of the failure of this film.

Mouse knocks on cat's noggin...

...inquires brusquely: "Hey, stupid. Lose somethin'?"

Cat notes disappearance of "nice bowl of milk."

Freeze-frames of special effects moments are fun.

Cat voices a common Avery plaint: he's hungry! Mouse decides to investigate.

Devon: Here's work by Rod Scribner, when the phantom mouse looks into the cat's empty tummy.

Cat's mouth has the sound effects of a rattly 1935 Ford, with echoey metal and squeaking joints.Mouse does crossed-arm thing as he slams cat's "hood" shut. Is convinced feline needs nourishment.

Devon: Here's Virgil Ross--the hands are a dead giveaway.

Addressing cat as "Slug," mouse suggests his species for dinner. Talk about stacking the deck!

Cat is into the concept.

This is a poor narrative choice. The cat, who is innocent of wrong-doing and in dire straits, is led into agreeing to something that will bring him much torment. It's one thing to bait a yokel, as Bugs, Daffy and Screwy Squirrel so often do. It's another to prey upon their weakness and then condemn them for a disagreeable choice.

Since this is considered an insignificant cartoon, no one bothered to ask Avery about his motivation in devising such a profoundly flawed thesis. He might have shrugged it off. Avery was a perfectionist, and the holes in this storyline would seem self-evident.

It's painful to see such artistry--from animators Scribner and Ross to composer Carl Stalling--squandered on a poor narrative. But it happened, and we're going to see it through to its unpleasant end.

Cat takes bait; mouse has his contract to murder one feline.

Some abstract squashes as cat instantly slams against mouse-hole; bounces back.

Re-appears. "Hello, jerk," mouse says; mouse retreats.

Cat realizes what he--and we--are in for. There's a moment of silent empathy.

Cat looks at us as if to say "help."

More Scribner animation on the cat, as noted by Devon: "Already the tendencies of the Bob Clampett era are showing up...those folds in the cat's fur, etc."

Next is a gag idea that will be done far better in two years, with the M-G-M cartoon What's Buzzin', Buzzard? (Object of pursuit joins in with antagonist; antagonist takes l-o-n-g time to figure it out.)It's one of the film's few genuinely funny moments because it doesn't require the mouse to be lethal towards the cat.

Here are screen shots of the similar and superior version from '43:

(Someone please put up the money to restore Tex Avery's M-G-M cartoons. They're a national treasure and they've been treated like garbage for decades.)

Despite the lapse in cartoon physics--no living being can catch a phantom--the cat's natural instincts are revved up, and he's going to pursure this inedible specter to his own demise.

The ghost-mouse's materializations are cleverly done. This one's my favorite.

"Did you get me, punchy?"

A gag idea that Avery (and others) put to better use elsewhere is graced with beautiful character animation and Stalling's spot-on "guidance" cue, played by an expressive violin.

Cat does much head compression before he gives with a take.

Much dramatic swatting of dead air; more great animation to no avail.

Devon: "Hello again!" Meanwhile, Leon Schlesinger is

wriggling restlessly in his seat...

Some more great Scribner folds, squishes and stretches.

Cartoon Law of Physics 479-D: When necessary, a furred character's pelt can be rolled up, like a shirt sleeve--if the character needs to reach into a hole where physical harm will result.

Now come two swift acts of malice. First, a good ass-kick...with prolonged drum-roll that causes the viewer to feel the anticipation of an unseeable force...

Scribner's loosy-goosy, limb-flailing animation--at times the cat remarkably resembles the early Sylvester in his body language and posing--gives us the only joy in the moment.Now we get into Herman and Katnip territory. This is just plain painful to witness.

An Avery aside to the viewer does nothing to salve the brutality of the moment.

What's next? A hotfoot? The ol' tongue-pulled-taut-then-flaps-like-a-windowshade bit?

...

Huh. A floating pencil. Let's follow it!

Well, that wasn't worth the effort that went into it.

Despite some fine Rod Scribner poses, I must concur with Devon's comment:

"The tickling stuff goes nowhere... In fact, none of this has much of a payoff."

I do like the post-coital position the cat assumes for a few seconds.

Next torment!

Funny as a cry for help.

More great Scribner stuff (if nothing else)...

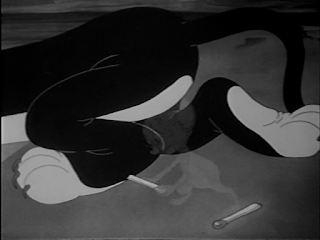

Mouse does the kiss-as-humiliation gag--a sublime moment in the recent A Wild Hare, but meaningless here.Ahhh... now it's hot-foot time. Let's see if it's done any faster than in our prior subject, Of Fox and Hounds...

The mouse's contempt for the cat is shown by his striking the match on the poor critter's tookus.

Devon: Some inspiration here--the cat's look to the audience before his imminent pain.

Expressive poses bring some class to an unclassy gag.

At least we're now 40 seconds from the end.

The resulting SFX take a small eternity to peter out. With them goes the cat from this mortal animated coil.

"Too bad," Tetley-mouse tsk-tsks.

"Aaah, but th' slug haddit comin' to 'im!"

Devon: Um, I call BS on that.

(So does your humble blogger here.)

As mouse further attempts to justify his brutality, ghost-kat climbs over the windowsill. This inspires a beautiful, subtle take that is timed and animated to perfection, despite the wrongness of it all.Some prints of this public-domain cartoon are mighty hard to suss out at this point. Those transparent ghosts against a light sky tend to disappear.

Mouse anticipates the glut of "Casper, the Friendly Ghost" cartoons to come. Like the equally weak ending of the Avery masterwork Slap Happy Lion (M-G-M, 1947), the gag trades on an entity being afraid of another version of itself. Like the tongue-flapping-like-windowshade bit, it's a joke that never works. It's a fitting end for this misbegotten cartoon.

Thank heavens, it's over. Devon notes:

"Mike Maltese told Joe Adamson that, originally, nine ghost cats were going to chase after the mouse. What an expense that would have been in an already-elaborate production."

Perhaps. But karmically, it would have been a more apt closing for this troubled 'toon. Visually, there's nothing to fault in The Haunted Mouse. The animation is full of skillful nuance, convincing volume, contour and movement. Carl Stalling's score tries hard to persuade us that what we're watching is, indeed, worth our seven minutes and change. It's a magnificent but wasted effort.

One hopes that a lesson was learned from this expensive experiment. The audience has to feel convinced that the antagonist is worthy of censure, attack and defeat by the put-upon protagonist. Here, the protagonist is not anyone we can care about. He had a hard life as a mouse. Nature is merciless, but his twisted agenda isn't the same as, say, Elmer Fudd's misguided attempts to hunt, or Yosemite Sam's short-fused temper (and failure to understand that because he reacts, he encourages Bugs to goad him on further). Michael Maltese never made such a mis-step again in his long career. Avery did, for the sake of taking risks and probing the unknown, in search of the perfection of his comedic ideas.

His next (and last) black and white cartoon, Porky's Preview, will show that trying the unproven can reap wonderful results. I will try to be more regular with future posts. Some of the cartoons yet to come are as unrewarding as this one, but I'm in it to the end. See you sooner than you might think.

NEXT: Tex gives us the almost-razzberry:The Crackpot Quail

I'm surprised you didn't note that despite being lifelong friends, Avery and Maltese did not get along on the job. At this point Maltese was too green to know any better, so I would pin most of this cartoon's failure on Avery. By the time they worked together again at Lantz in the '50s, it was a different story. Maltese developed a "auteur" view more than any other writer in cartoons, and it needed to work in tandem with a strong director and story editor that appreciated it. He didn't last more than a few years with Freleng despite mostly spectacular results (Maltese "didn't write stories," said Friz), and the stuff at Lantz and Hanna-Barbera yielded no masterpieces. But he and Jones were soulmates (if not friends) precisely because Maltese found a sympathetic ear willing to try new things more than any other director in mid-century American animation.

ReplyDeleteTHE HAUNTED MOUSE is awful, of course, but I do quite like THE CRACKPOT QUAIL - wherein any abuse Willoughby suffers is too ridiculous to take seriously/painfully.

I didn't know that Avery and Maltese didn't mix well at work. I agree that the finger of blame is on Avery here. He tried something that just doesn't work.

DeleteI haven't seen CRACKPOT QUAIL in awhile, but I'll view it with an open mind. You would know this--wasn't the original version released with the quail making a "razzberry" sound instead of the whistle that he blows trying to keep his quail-thingy out of his face? Or was that nixed by the censors before release? I've never been able to get a clear account of this. As always, thank you for your astute and welcome comments.

Yes, it exists, as Jerry Beck says he saw it (I'm sure the 35mm is housed at UCLA). He says just picture the current cartoon, except with constant farting. I wish it would surface on a collection some time in this lifetime.

DeleteMike Maltese's first credited story, and it's kind of appropriate they spelled his name wrong in the credits, since it doesn't feel like a Maltese cartoon, and really doesn't feel that much like an Avery one, either.

ReplyDeleteAvery in “A Wild Hare” set up his story for the audience to sympathize with Bugs, but in “Of Fox and Hounds” set things up so that the audience's sympathies were with Willoughby. In this one, the audience's sympathies are with … nobody, because the cat isn't lovably dumb the way Willoughby is. He's just stupid, while the mouse (and Tetley's voice for him) exudes contempt for his adversary. We don't see retribution for the contempt until the final gag, and without the nine cats bit, all we get is the scared mouse running away.

Avery and Maltese would tackle the same problem of wise guy vs. dumb non-Fuddian adversary in far better fashion with “The Heckling Hare” (where the minute Bugs shows open disdain for Willoughby the cartoon gods have him fall through the hole into the death plunge with the dog. Which would basically hold true for the rest of Bugs' career -- he could be a stinker, but just about every time he became a contemptuous braggart about it, the in-cartoon retribution would be swift, even if the setback was only temporary).

I think Tetley's voicing adds a lot to the mouse's mean-ness. Tetley sounds angry throughout, and that is counter-intuitive to the design of these cartoons. The beauty of the best Bugs Bunny cartoons is that Bugs never allows himself to get ired--unless it's the last straw AND it pushes the story ahead. Otherwise, he remains unflappable--cheerful, even--as his antagonist stews, simmers and loses it.

DeleteAGreed..I knew a number of years ago about Tetley being the voice of the mouse from one of the newsgroups (rec.arts.animation, being one, I think) passed down from one of the historians..

DeleteWhere did you found that print?

ReplyDeleteLooks pretty good compared to the one that is on internet.

Also it can be useful for me, since i fansub looney tunes cartoons.

I got it in a trade. It is a beautiful print for a public domain film. I can share my copy with you if you like.

DeleteIn the Tex Avery bio book, Tex himself says "you got 6 weeks to storyboard a cartoon. Then after 6 you just had to proceed to the next phase, good or bad". I think this was just such as case of Tex finishing the cartoon because he had to fill the schedule.

ReplyDeleteAlthough this is officially a one-shot Looney Tunes cartoon, the unnamed cat sure looks like a prototype version of Sylvester to me. Sylvester would make his official debut 4 years later, in 1945.

ReplyDelete