DVD-Blu-Ray Availability: Looney Tunes Platinum Collection: Volume 2 (available in both formats)

You may view the complete version of this cartoon HERE.

<><><><><><><><><><>

PREFACE: This will be the longest, most involved chapter in this blog. It marks the fifth year of this quixotic ode to one of my favorite filmmakers.

When I started this blog in 2013, I assumed I'd breeze through Tex Avery's Warner Brothers cartoons in a year or two. Life had different plans for me. With luck, I'll reach the end here by 2023, assuming the free Internet, blogs and computers still exist, and we're not talking into sentient sticks and beaming our thoughts into some shared cephalopodic mind-screen.

I have been mesmerized by animation since infancy. The first motion picture I saw was a revival of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in Tallahassee, Florida in 1965. My grandmother later delighted in recalling my sheer terror at moments in the film, but I wasn't traumatized--just fascinated and compelled to see more, at a point when I might not have been able to discern live-action footage from hand-drawn animation.

Television had loads of limited-animation programming, but, as I discovered, early in the morning, local stations showed older cartoons. They looked, sounded and felt different. Like Snow White, they convinced me more of real-life movement than the mechanical walk cycles of The Flintstones, or the illustrated radio of Rocky and Bullwinkle.

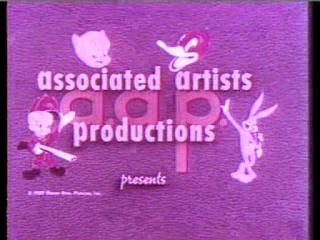

The cartoons that interested me most came from a large package of Warner Brothers shorts purchased by Associated Artists Productions. This image, and not the iconic Warner Brothers rings, opened the cartoons I saw on early morning and afternoon TV broadcasts:

It became easier to connect the dots: William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, producers of so much TV dreck, did those beautifully-animated Tom and Jerry shorts of the 1940s! Animators who worked for Disney also worked for M-G-M, Lantz and Warner Brothers!

It became easier to connect the dots: William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, producers of so much TV dreck, did those beautifully-animated Tom and Jerry shorts of the 1940s! Animators who worked for Disney also worked for M-G-M, Lantz and Warner Brothers!

One early godsend was the January-February 1975 issue of Film Comment with a large section on classic Hollywood cartoons--a suite of articles that coalesced with the critical thinking I'd begun about these films. The discovery of this issue, in 1979, gave me a sense of purpose in my interest in animation. These were films worth thinking about and studying. They weren't expressly made for children. They had value as containers of American popular culture and history.

When I started this blog in 2013, I assumed I'd breeze through Tex Avery's Warner Brothers cartoons in a year or two. Life had different plans for me. With luck, I'll reach the end here by 2023, assuming the free Internet, blogs and computers still exist, and we're not talking into sentient sticks and beaming our thoughts into some shared cephalopodic mind-screen.

I have been mesmerized by animation since infancy. The first motion picture I saw was a revival of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in Tallahassee, Florida in 1965. My grandmother later delighted in recalling my sheer terror at moments in the film, but I wasn't traumatized--just fascinated and compelled to see more, at a point when I might not have been able to discern live-action footage from hand-drawn animation.

Television had loads of limited-animation programming, but, as I discovered, early in the morning, local stations showed older cartoons. They looked, sounded and felt different. Like Snow White, they convinced me more of real-life movement than the mechanical walk cycles of The Flintstones, or the illustrated radio of Rocky and Bullwinkle.

The cartoons that interested me most came from a large package of Warner Brothers shorts purchased by Associated Artists Productions. This image, and not the iconic Warner Brothers rings, opened the cartoons I saw on early morning and afternoon TV broadcasts:

My family didn't get a color TV until 1976, so my earliest views of these, and the classic M-G-M cartoon library, plus Famous Studios, Terrytoons, Walter Lantz and the odd Disney short, were in grainy, low-rez black and white.

As a child, I had no clear idea how old these cartoons were. I knew they preceded my birth, and that the Hanna-Barbera TV cartoons--plus the other contemporary ventures into limited animation that dominated broadcast time--were more recent. No reference books existed, and there was no way to summon up a cartoon at a moment's notice.

Local TV stations randomly ran their 16 millimeter prints of these films, three to four in a half-hour time slot. Cartoon endings were regularly cut off if the show went into overtime (i.e., exceeded the time alloted to ads). More than once, film broke during a live broadcast. Said cartoon would often next be seen missing a hunk of footage, causing an interruption like a skip on a vinyl record.

These cartoons were time-fillers to pad out afternoon and wee-hour programming, sell advertising space to (usually) local merchants and give children something to stare at, and thus keep out of trouble/their parents' lives.

Few people, aside from kids, cared about these broadcasts. The television stations cared about the ads that they packed in-between these shorts. A passing adult might chuckle in remembrance of seeing such cartoon fare in their childhood. And there must have been older animation enthusiasts who had some inkling of knowledge of the art form's history, and who watched these crummy broadcasts as a means to see these elusive films.

That's what I became in my latter years of high school. The golden hours of 3 to 5 PM offered a chance to see x number of cartoons daily--at this time, a mix of Warners, M-G-M and Walter Lantz material, programmed with no rhyme or reason. By then. I'd gleaned first insights behind how these remarkable films came to be--mostly misinformation, but at this time (circa 1978) any info was welcome (if later refuted by proven fact).

It became easier to connect the dots: William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, producers of so much TV dreck, did those beautifully-animated Tom and Jerry shorts of the 1940s! Animators who worked for Disney also worked for M-G-M, Lantz and Warner Brothers!

It became easier to connect the dots: William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, producers of so much TV dreck, did those beautifully-animated Tom and Jerry shorts of the 1940s! Animators who worked for Disney also worked for M-G-M, Lantz and Warner Brothers! One early godsend was the January-February 1975 issue of Film Comment with a large section on classic Hollywood cartoons--a suite of articles that coalesced with the critical thinking I'd begun about these films. The discovery of this issue, in 1979, gave me a sense of purpose in my interest in animation. These were films worth thinking about and studying. They weren't expressly made for children. They had value as containers of American popular culture and history.