DVD/BLU-RAY AVAILABILITY:

Looney Tunes Golden Collection, Vol. V(Warner Brothers DVD 112172)

You can watch a restored version of this cartoon (with commentary by animator Mark Kausler) HERE. Enjoy!

We've recently examined the brief but painful down period for the Fred Avery unit at Leon Schlesinger's cartoon mill.

The mid-to-late 1930s were not great times for Hollywood animated cartoons. Significant breakthroughs in animation, color and film technique occurred, many of them pushed forward by Walt Disney and his technical staff. These would benefit the artform's decade-long peak in the 1940s. With a focus on improving the visual aspect of animation, the core content of studio releases faltered.

Disney's innovations sent shock waves through the animation industry. Studios indifferent to change, such as Paul Terry's, showed striking improvements in the quality and personality of their animation. Disney's visual improvements over-emphasized technique and de-emphasized content. That negative influence spread like cancer in cartoons of 1934-1940.

The cartoons Leon Schlesinger produced for Warner Brothers particularly suffered. Liminal cartooning, stuck in the Art Deco style of the earlier '30s, with an occasional tiptoe towards a new look, makes these cartoons seem stale and awkward to our 21st-century eyes. Timing, humor and characterization tend on the dull side, despite some forward-thinking flashes.

Tex Avery and Frank Tashlin consciously strove to break through this barrier of mediocrity through clever technique and, most vitally, a focus on the content of their pictures.

Warner Brothers' cartoons, pre-Avery, were never marvels of storytelling. Plot elements in the earliest releases, supervised by Hugh Harman and Rudy Ising, are mere scrawls. The 1933-36 releases make the Harman-Ising cartoons seem plotty and complex.

Tex Avery increased the substance of the animated cartoon from the start of his tenure at Schlesinger's. From Gold Diggers of '49 on, we see a pointed effort to make each film about something, rather than a bazaar of vaguely related, non-narrative moving images.

Solid storylines offered a stronger base for characterization and humor. It also gave the audience more engagement and interaction. Avery and Tashlin furthered this effect by having their characters address the audience, often in a challenging or aggressive way.

Avery pushed harder by his development of a brace of devices that shattered the tacit contract between film and viewer--that we will buy into the illusion of the flickering image on-screen.

Little Red Walking Hood brings a new sophistication to this no-fourth-wall agenda. Avery will continue to build on this cartoon's innovations for the rest of his directing career.

A few early Avery cartoons lack their original credit sequences, due to their "Blue Ribbon" re-issues of the 1940s. None of the 1936/7 color cartoons' original openings have yet been found (so far as I know; I could be wrong).

This appears to be the first Avery cartoon in which the title becomes part of the cartoon's action. The credits are painted on a textured leather book cover, which opens, to reveal the first page of a mock-fairy tale:

This was already an animation cliche. The opening storybook, with its "Once upon a time" opening, might have sent groans through the cartoon's 1937 audience. Not another fairy-tale!

Those patient enough to read the text, upon the sight of the phrase "nearby pool hall," might have laughed in relief. Maybe this was gonna be something, after all!

We open on that ugly, liminal animation--its emphasis on mirror-like proportion, rather than depth and contour.Circles, rather than ovals, force character design away from graceful poses.

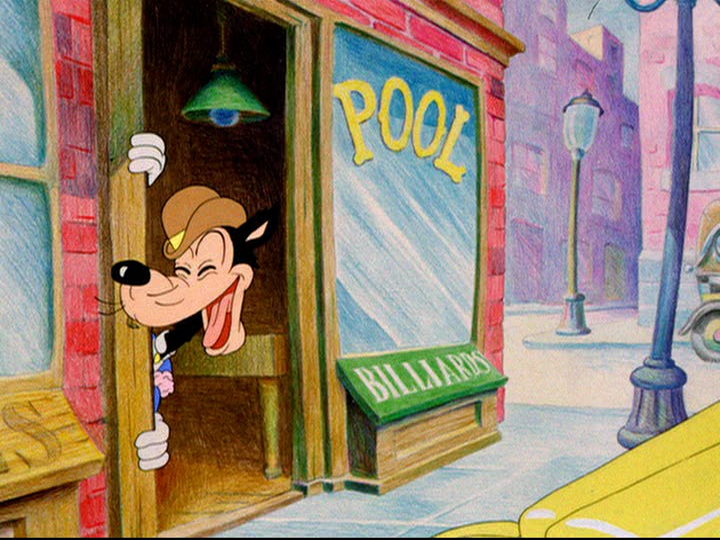

That the wolf is, indeed, in a 1937 pool hall, playing a pinball machine (and cheating) helps to abrade the fairytale's potential for schmaltz:

Avery's fondness for diagrammatic shots will increase over time. They're a staple of his M-G-M cartoons.

Mean Old Wolf is shown to be (a) a lowlife and (b) an unsuccessful player (and playa). This first iteration of the Avery wolf-lecher is mild by his later standards.

As astute reader J Lee notes in his comment (please check out the comments, as there's often great stuff in them), Mean Old Wolf is a new kind of character for Avery--the completely comical villain. I heartily agree with Mr. Lee's point, and think it's well-stated.

Meanwhile, the wolf's lechery is quickly established:

Those patient enough to read the text, upon the sight of the phrase "nearby pool hall," might have laughed in relief. Maybe this was gonna be something, after all!

We open on that ugly, liminal animation--its emphasis on mirror-like proportion, rather than depth and contour.Circles, rather than ovals, force character design away from graceful poses.

That the wolf is, indeed, in a 1937 pool hall, playing a pinball machine (and cheating) helps to abrade the fairytale's potential for schmaltz:

Avery's fondness for diagrammatic shots will increase over time. They're a staple of his M-G-M cartoons.

Mean Old Wolf is shown to be (a) a lowlife and (b) an unsuccessful player (and playa). This first iteration of the Avery wolf-lecher is mild by his later standards.

As astute reader J Lee notes in his comment (please check out the comments, as there's often great stuff in them), Mean Old Wolf is a new kind of character for Avery--the completely comical villain. I heartily agree with Mr. Lee's point, and think it's well-stated.

Meanwhile, the wolf's lechery is quickly established:

Compared to Red Hot Riding Hood, or other M-G-M cartoons, the wolf's reactions are mild. At this stage, Avery is still cautious in his use of takes. In 1937, showing strong, unmistakable sexual desire on-screen was, itself, a minor victory.

Car-as-arousal totem makes its first appearance in the Avery universe, as Wolf stalks his sexual prey in a modern, streamlined way...

Car-as-arousal totem makes its first appearance in the Avery universe, as Wolf stalks his sexual prey in a modern, streamlined way...

You have, by now, noticed the curious renderings of the background scenery. In an on-the-job experiment, Avery's background artist used colored pencil in lieu of watercolor, gouache or ink wash--the traditional tools for cartoon scenics. It's a clever switch, but the sketchy rendering can be a distraction.

On cable TV, in 1980s film-chain broadcasts, these backgrounds were softened up, and looked charming. This restored version brings out the powerful hues of the pencils, but shows their limitations as a rendering tool. Applause for trying something different. Now back to our cartoon dissection.

One can see Avery's hand in the character designs. The animation continues to suffer from the too-symmetrical look and feel. The arrival of Irv Spence, who helped bring Avery's visual style kicking and screaming out of the moldy-fig school, is highly anticipated.

Getting no traction from a basic greeting, Wolf puts his custom license plate to good use:

Red addresses us with a proto-feminist speech. It's obviously meant to amuse the audience, in that she's non-chalant and analytical, instead of having a bellicose, negative response. Spence's animation makes her character come to life:

"Really, in this modern age of flaming youth, a girl has to put up with such embar-rassing situations... really, we do..."

"Don't we, girls? Two-thirds of you girls out there have gone through just what I'm going through now..."

Egghead, redesigned from his prior appearance (which you can read about HERE), is a pleasingly stylized, more modern-looking figure, abetted by Spence's deft line and posing.

Shorn of that crutch, this cartoon offers the first true expression of Avery's modern, assured sensibility. Despite highly variable animation and a still-measured pace, Avery's unit moves several significant steps closer to its classic style here.

Back to our picture. Dissolve to the countryside. At this point, Little Red Walking Hood sheds any pretense of being normal Hollywood product. Like Uncle Tom's Bungalow, it becomes another grand-standing meta-cartoon, more concerned with breaking rules than maintaining a storyline. That's fine.

Mean Old Wolf sees and hears his enigmatic adversary, and, in a return to the effects of Avery's first Schlesinger picture, steps up the speed:

An unusually tan Grandma comes to the door. The Roosevelt-esque portrait to her right is rather distracting.

The meta-play is in full swing now. Neither Wolf or Granny are genuinely the characters they portray.

Red finally appears.Wolf panics, like a guilty high-school kid trying to clean house after a wild party.

We now reach the "money shot" of the Little Red Riding Hood narrative...

We cut to Irv Spence, who animates the rest of the cartoon. We know we're in good hands.

Spence's distortions in this fight cycle are fascinating to view, either still-frame or in animated form:

On cable TV, in 1980s film-chain broadcasts, these backgrounds were softened up, and looked charming. This restored version brings out the powerful hues of the pencils, but shows their limitations as a rendering tool. Applause for trying something different. Now back to our cartoon dissection.

One can see Avery's hand in the character designs. The animation continues to suffer from the too-symmetrical look and feel. The arrival of Irv Spence, who helped bring Avery's visual style kicking and screaming out of the moldy-fig school, is highly anticipated.

Getting no traction from a basic greeting, Wolf puts his custom license plate to good use:

Note how the dash disappears!

Still nuthin'.

"Hello, pretty girl! [nasally] Going my way, babe?"

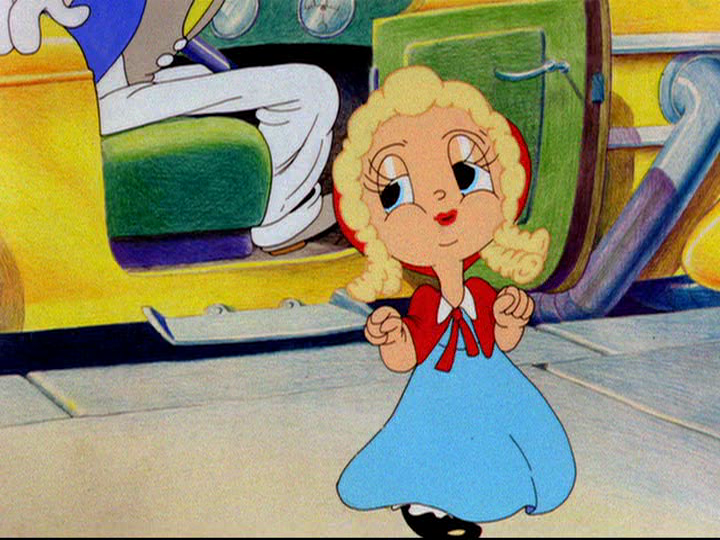

Irv Spence now takes over the animation. Red Riding Hood, as are many of Avery's heroines, uses a Katharine Hepburn voice. Apparently, Hepburn's affected vocal mannerisms, to Avery, were the nth degree of Hollywood sham and facade.Red addresses us with a proto-feminist speech. It's obviously meant to amuse the audience, in that she's non-chalant and analytical, instead of having a bellicose, negative response. Spence's animation makes her character come to life:

"Really, in this modern age of flaming youth, a girl has to put up with such embar-rassing situations... really, we do..."

"Don't we, girls? Two-thirds of you girls out there have gone through just what I'm going through now..."

"You know how it is, don't you, girls?"

Without addressing the wolf, she walks off, aloof. This is a remarkable moment of cool for 1930s animation. Though parodic, it's arguably a more real moment than anything in live-action Hollywood of 1937.

The direct, sympathetic address to women in the audience was twofold: cynical men could laugh at this absurd-yet-calm outburst, and women might quietly nod their heads in agreement. It's a striking moment, and one only Avery and his writers could have so convincingly brought into animation.

The direct, sympathetic address to women in the audience was twofold: cynical men could laugh at this absurd-yet-calm outburst, and women might quietly nod their heads in agreement. It's a striking moment, and one only Avery and his writers could have so convincingly brought into animation.

Frustrated, Mean Old Wolf is further thwarted by a physically aggressive stoplight:

Irksome whistling catches the wolf's attention, once he recovers from the blow.

The author of that inane whistle makes his Spence-animated screen entrance, stage left:Egghead, redesigned from his prior appearance (which you can read about HERE), is a pleasingly stylized, more modern-looking figure, abetted by Spence's deft line and posing.

Sans Spence, the stoplight gets in one more lick:

Wolf snaps out of stars-and-birdies mode, adjusts derby, and prepares to accelerate.

Like Peter Parrot in our last cartoon, I Wanna Be A Sailor, Mean Old Wolf has a casual pre-war rap prepared (the lyrics to a contemporary pop song, "Gee, But You're Swell")--in this case to further woo his San Quentin quail...

It's a remarkable vocal performance. This sequence takes up over a minute of the cartoon's 7:42 runtime, and the contrast of the highly risible, ego-centric wolf, who goes from pose to persuasive pose, to Red's Bette Davis-style disdainful walk cycle, is genuinely amusing.

You can, no doubt, spot a metaphor coming.

Like any good sociopath or narcissist, Wolf makes sure to self-aggrandize, and his closing lines, before a mailbox interrupts, are telling.

A tighter medium shot emphasizes the wolf's ego-boosting blather:

The Wolf's main selling point is that any girl, riding-hooded or otherwise, would be lucky to be with "me! A big shot like me!"

Wolf seems convinced by his own spiel.

Mailbox provides sobering nudge of reality/perspective.

Red gives another calm-and-collected speech, ending with the essential 1937 kiss-off: "Scram!"

Before Wolf can grok the rejection, the mailbox, most recently a foe, proves an ally.

This bit of business flashes forward to Avery's Droopy cartoons of the 1940s, in which another cipher protagonist both goads and rewards his unapt nemesis.

Avery cars love tight S-curves.

Big step forward: there's no narrator. Avery's innovative use of the off-screen commentator, in The Village Smithy and Uncle Tom's Bungalow, implied that he wasn't 100% confident that his screen-busting humor would work on its own.Shorn of that crutch, this cartoon offers the first true expression of Avery's modern, assured sensibility. Despite highly variable animation and a still-measured pace, Avery's unit moves several significant steps closer to its classic style here.

Back to our picture. Dissolve to the countryside. At this point, Little Red Walking Hood sheds any pretense of being normal Hollywood product. Like Uncle Tom's Bungalow, it becomes another grand-standing meta-cartoon, more concerned with breaking rules than maintaining a storyline. That's fine.

Mean Old Wolf sees and hears his enigmatic adversary, and, in a return to the effects of Avery's first Schlesinger picture, steps up the speed:

Nothing shall impede his well-worn path to Granny's cottage.

The wolf borrows from radio with his line, "I hope the old Grandma's t'home, I hope I hope I hope I hope." Mark Kausler IDs gagman Tedd Pierce as the Wolf's voice.An unusually tan Grandma comes to the door. The Roosevelt-esque portrait to her right is rather distracting.

Granny breaks into song, with "Wolf, Stay Away From My Door." This heps us that she, too, is in on the meta-joke, and that she'll be a good sport about it all.

Tip: When Irv Spence animation starts, you know it's going to be a good scene. Some of Spence's pencil drawings for this bit can be seen in Joe Adamson's groundbreaking book Tex Avery: King of Cartoons.

Egghead, like Droopy in the 1940s M-G-M cartoons, breaks the laws of time and space, as it suits his needs.

Then this happens...

Seven successive doors. Granny waits at the back door to end the cycle.

File what happens next under "NEVER FUNNY." Along with the tongue-flapping-like-cheap-windowshade bit, this gag was used to death by all the cartoon studios, despite its obvious lack of amusement value:

The next bit is a strong early example of Avery's metaphorical comedy. It foreshadows a better variant, in Avery's 1939 masterpiece, Thugs With Dirty Mugs:

Whoops! The exposures got out of whack. As the wolf enters, four ghostly rhomboids float over him.

This is a literally show-stopping sequence. The banality, and length, of the conversation are as much the joke as the interruption:The next bit is a strong early example of Avery's metaphorical comedy. It foreshadows a better variant, in Avery's 1939 masterpiece, Thugs With Dirty Mugs:

Whoops! The exposures got out of whack. As the wolf enters, four ghostly rhomboids float over him.

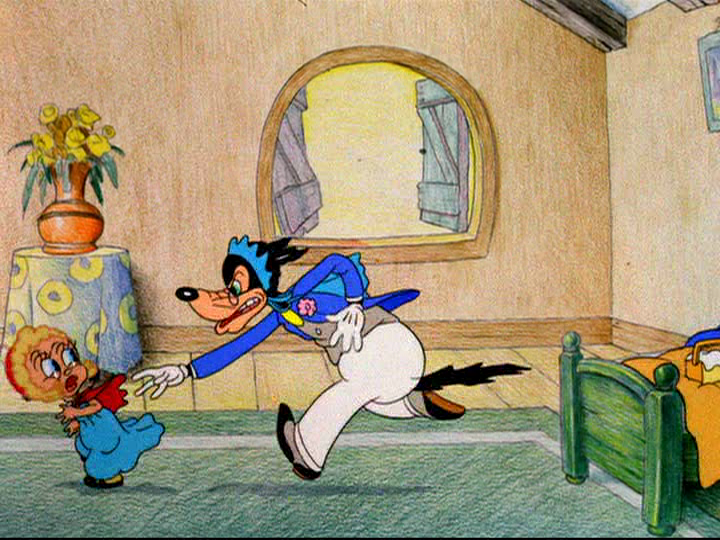

Anyway, he's in, and the required chase can begin.

A phone call interrupts.

Granny calls a "King's X" time-out.

"Will you people pardon me just a minute?"

"Let me see..."

"[embarrassed] Heh... it's the grocer, folks..."

Wolf is frustrated at this rambling delay.

With "a case of gin," Granny's home shopping is complete.

We now resume our previously scheduled programming.

Irv Spence returns. The discrepancy of his and the other animators' work parallels Jim Tyer's scenes in the 1950s Paul Terry cartoons. According to Mark Kausler, Spence was more methodical in his scenes. Regardless of their working style, both men created dynamite animation. (Kausler's commentary on the linked version of this cartoon has some interesting info on Spence.)

Egghead further bollixes the wolf.

A shrug and a "whaddaya gonna do?" expression are the only possible reactions.

Avery ramps up the acceleration in this cartoon. The following screen shot took many tries to capture, so fast is its movement and timing.The meta-play is in full swing now. Neither Wolf or Granny are genuinely the characters they portray.

The slapping...

and nose-honking...

...anticipate Bugs Bunny's playful pranking of Elmer Fudd in A Wild Hare (1940).Red finally appears.Wolf panics, like a guilty high-school kid trying to clean house after a wild party.

"Gimme the stuff! Come on! Gimme the stuff!"

Granny complies, and transfers specs, bonnet and shawl to the wolf.

She seems pleased with the meta-ruse.

Here's another action that plays so quickly it took eight tries to get the screen-grab. The acceleration of certain scenes here is quite impressive.

Might as well get this part over with...

Red's high-functioning vocabulary is amusing.

"Rather childish and a bit silly, don't you think?" Red asks us of this interminable scene.We now reach the "money shot" of the Little Red Riding Hood narrative...

We cut to Irv Spence, who animates the rest of the cartoon. We know we're in good hands.

Spence's distortions in this fight cycle are fascinating to view, either still-frame or in animated form:

Red breaks away to speak to us once more.

"Silly way to make a living, don't you think?"

It's thrilling to witness the birth of a notion. Here is Avery's first use of a brilliant breakthrough concept--to include silhouettes of late theater-goers as they sidle through the seats, breaking the spell for everyone--from audience to cartoon characters.

"Hey, Red. Wait a minute."

"Let's wait til THESE PEOPLE get SEATED..."

"...then we'll go ON with this thing!"

As with many of Avery's grand stunts, this had no precedent for its late 1937 audience. Moviegoers dealt with this annoyance all the time. To have it (a) happen on-screen and (b) interrupt the picture must have been mind-blowing to the cartoon's first viewers.

"Okay, let's GO!" Wolf says, impatient as a Little League coach.

This skirmish hasn't a chance.

"Hey, bud! Just a minute, bud!"

"Now, who the heck ARE you, anyway?"

"Who, me?" Mel Blanc-as-Egghead says, in an ancestor of Barney Rubble's voice.

"I'm the hero in this picture..."

Blanc-head then cackles like an imbecile.

Never trust the iris-out.

Indeed, a new aperture opens, to show Egghead kissing Red.

She seems to like it, as the new iris dwindles.

As we've seen in Uncle Tom's Bungalow, Avery and his crew still haven't figured out how to maintain a narrative while also savaging its every foundation. It wasn't yet certain if both things could co-exist. Someone had to take these steps, break through safety nets, and see what happened.

Both these films feel slight in plot. It's important to remember that, in 1937, their methodical slaughter of illusion was, in itself, a big deal for moviegoers. This was heady stuff, and each cartoon takes new steps down an exciting path.

As said, Little Red Walking Hood earns props for losing the narrator. Avery and his gagmen clearly felt confident in the act itself, rather than the act described and commented upon. That, and the fourth-wall-demolishing silhouette routine, make this a vitally important cartoon in the Avery resume.

The Avery unit is out of its miasma, and newly focused. I'd love to know what happened to bring this sea-change about, but it will bring some great and groundbreaking cartoons to the screen in 1938 and 1939.

Thanks to Thad Komorowski for debating an original statement in this essay and causing me to rethink and restate it. I'm not perfect, and sometimes my thoughts don't translate into written words as I imagine they do.

NEXT: Happy New Year, 1938: Daffy Duck and Egghead

Both these films feel slight in plot. It's important to remember that, in 1937, their methodical slaughter of illusion was, in itself, a big deal for moviegoers. This was heady stuff, and each cartoon takes new steps down an exciting path.

As said, Little Red Walking Hood earns props for losing the narrator. Avery and his gagmen clearly felt confident in the act itself, rather than the act described and commented upon. That, and the fourth-wall-demolishing silhouette routine, make this a vitally important cartoon in the Avery resume.

The Avery unit is out of its miasma, and newly focused. I'd love to know what happened to bring this sea-change about, but it will bring some great and groundbreaking cartoons to the screen in 1938 and 1939.

Thanks to Thad Komorowski for debating an original statement in this essay and causing me to rethink and restate it. I'm not perfect, and sometimes my thoughts don't translate into written words as I imagine they do.

NEXT: Happy New Year, 1938: Daffy Duck and Egghead

The other thing groundbreaking in this cartoon was the idea of the purely 'comic villain'. Cartoon bad guys in the past could be used as the source of a few gags, but they were always supposed to provide a certain real sense of menace to the other character(s). Even in "Uncle Tom's Bungalow" Avery's still asking us to take Simon Simon Legree just a little bit seriously.

ReplyDeleteNot here. From the moment he shows up at the pinball table, the wolf in this short is only there to be needled to death by the two other characters and any other objects on-screen. What that meant was Avery could finally jettison any need for faux-drama with the bad guy and turn him basically into one seven-minute punchline. (Clampett would follow the same path at roughly the same time with the Gorgon in "Porky's Hero Agency"). It would still take Warners a little while to completely break free of the Disney story structure mindset, but the revelation here was you could do Disney personality animation on a completely comedic level and not only didn't it hurt the cartoon, it made it vastly better as long as we cared about the characters.