6/9/1936

DVD/BLU-RAY AVAILABILITY:

Looney Tunes Golden Collection,

Vol. VI (Warner Brothers DVD 115871)

You can watch a nice color print of this cartoon, with commentary by Will Friedwald, HERE. If you're not familiar with this cartoon, please watch before you read--thanks!

As I anticipated (and dreaded) when I began this blog, it has proven difficult to look beyond the mere trainspotting of facts, figures and rumors that seem to obsess many fans of classic animation.

That is not what this blog is about. I hate to repeat myself, but I guess I must. My sole intention with this blog is to examine the development of Fred "Tex" Avery as a humorist, movie-maker and pop-culture influence. It is not to determine who did what, when, where, or why.

Yes, animation is a team effort. Yes, some talented and very significant animation figures worked on these cartoons. Yes, there was behind-the-scenes intrigue. You can find that information readily elsewhere on the Internet. What you'll find here is MY personal look at the developmental efforts of a great film-maker. Please respect what I'm trying to do here. Thank you.

There seems to be some confusion about Avery's first color release. Was it this cartoon? Or was it I'd Love To Take Orders From You, the prior cartoon examined herein? I use release dates as the criterion for the lineage of the cartoons. According to the release date, (Page) Miss Glory was released on June 9, 1936... two weeks after Orders.

And, as many have wondered over the years... who in the world was Leadora Congdon? The studious, research-enriched "Yowp" offered this capsule explanation on an animation forum:

Apparently, Ms. Congdon made no great impact on the world, and this cartoon is her legacy. She was a talented student of the art deco school. She was not a highly original or outstanding designer, but she was in the groove of the futuristic expectations of mid-1930s America. The country was desperate to get out of the great rut of the Depression, and to embrace modernity and progress.

Deco design and animation were a feasible blend--Hector Hoppin and Anthony Gross' Joie De Vivre offers proof of that--and the mid-1930s animation art style sometimes hints at that level of stylistic streammline and contour. Hollywood confined its Art Deco tendencies to live-action (where deco and Expressionism would often get intermingled). Hoppin and Gross wander into Impressionism in the early moments of their film. The modernist slant of the cartoon's industrial and railroad landscapes, towards the film's end, is more in line with the general vibe of Art Deco.

Congdon appropriates some Expressionist motifs in her design work for (Page) Miss Glory, for which she is solely (and unfairly) credited. Fred Avery and his animators could not indulge in the meandering experiments of Hoppin/Gross. They had to deliver the Merrie Melodie goods--seven minutes of color, lively movement, and homage to a Warner Brothers-owned popular song.

Avery boldly works with Congdon's designs, and he seems determined to cram a great deal of humor into its very slight narrative. Far funnier than his Technicolor debut, (Page) Miss Glory offers some early inklings of Avery's idea of big city life--iconic images that became a strong part of his early MGM cartoon projects.

Milling skyscrapers, elevators that move at obtuse angles (or laterally) and block-long limousines with a dozen spare tires--iconic trappings of Avery's Red Hot Riding Hood (1943)--get their first workout here.

Late in life, Avery was dismissive of (Page) Miss Glory, when asked about it. The arrogation of credit may have still rankled him, as a reminder of Leon Schlesinger's thoughtless attitude towards his creative crew.

Or it may have been the dualism of his creativity. A restless experimenter, Avery seemed embarrassed by attempts that didn't succeed. He never lost his whim to test and experiment--his final theatrical cartoon, Sh-h-h-h-h-h (1955) is a major risk-taker--but a streak of perfectionism led him to later condemn some of those daring steps into the void.

(Page) Miss Glory is the most visually ambitious Warner Brothers cartoon, prior to Frank Tashlin's fevered (and deeply Deco-influenced) films of 1937 and '38. It says much about Avery's skill as a film-maker--and his work ethic--that he made a potential disaster work fairly well, and remain entertaining instead of obtuse.

The somewhat lumpen natural style of Schlesinger's 1936-model cartoons provides a natural contrasting set-up to the fanciful excursion into style that is Congdon's design work. (I'm unsure if her influence on the film included any hands-on final work, such as background painting. If not, the Schlesinger background artists were unusually adaptive in this case).

This stitched-together panorama of the film's opening shot displays the natural look-and-feel of the WB animation:

Blindingly bright primary colors, ugly character designs and a storybook style of watercolor/wash rendering--these elements SCREAM "1936 animation." The first-time viewer might regard this look-and-feel with the dread of longeur--yet another gormless, awkward mid-1930s Hollywood cartoon.

Inside the hayseed hotel, it's no better: Victorian clutter and a sense of must, dust and mildew. We meet Abner, the hick-town bellhop, who resembles Al Capp's recently-popular comic strip character in name and hair-do.

In these expressive poses, we see that Abner wants to emulate the big-city glitz of modernism. He makes the best of what he's got, clod-hopper shoes, suspenders and all...

The world around him is full of grounding reminders. A passing cow's moo

seems, at first, to be the bleating of a limousine horn.

The hamlet is all duded-up in anticipation of the arrival of Miss Glory. Why she's coming here isn't explained, but the general assumption is that she's the last word in Deco modernism--and thus at stylistic odds with the bucolic 19th century atmosphere of the cartoon's real world.

Abner grows bored waiting for Miss Glory's arrival, and takes a catnap.

Within moments, the first of Avery's zip code-length limos eases into the picture, and our Art Deco wet dream begins:

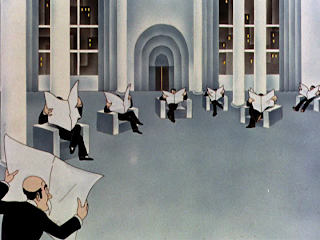

The Cosmopolitan Hotel is a streamlined, high-gloss world of tuxedoed dandies, monocles and chrome. Steely blue-grey replaces the warm earth tones of the old-fashioned inn. Deco-Abner is besieged by eligible bachelors, all clamoring for him to "page Miss Glory."

Bless his heart, Avery immediately works in a beautifully conceived and timed comedic episode--one that would have fit into Jacques Tati's film, Playtime (1967). The pictures put the gag across without a word from me:

It is a genuine relief to laugh at this smart moment. We realize that this isn't going to be seven sappy minutes of animated Busby Berkeley, nor sugary-sweet family entertainment.

The waiter's sudden red nose--and empty bottle--prepare us for an orgy of alcoholic preparation and consumption, as the first chorus of the title tune (another fine product of the Harry Warren-Al Dubin team) is crooned by The Varsity Three, with help by the eager Deco-Abner.

A startlingly weird POV shot, atypical for Avery, follows:

Avery is quick to deflate the artsy effect with the sudden belch of the drinker; a gloved hand enters the POV to stifle the eruction. We return to the prior set-up, but the effect of liquor have rumpled the Deco smoothness, to our surprise and laughter:

Mark Kausler tells me this fan-dance bit was animated by Bob Clampett.

It is priceless when the spotlight comes on--this fully transforms the socialite into the floor show.

Avery is on a roll, and immediately inserts another reversal of expectations:

Notably, we cut to a close-up as the punchline is delivered:

Miss Glory's arrival is announced, with characteristic cause-and-effect sequences. A gouty grandpa becomes airborne with excitement:

A sweaty steam-bather (working off a hangover?) emerges, sans spats:

a lobby of newspaper-readers quickly form a football huddle, and attempt a social touchdown.

He drops little counterpoints to the song, for comedy's sake and to keep the audience engaged. Abner fools with the complex elevator console, with each button-push sounded on a glockenspiel.

No earlier Merrie Melodie had attempted to play with the musical

presentation in this way. More typically, the characters stood stock

still while singing the song--sometimes with the lyrics, as in Freleng's

Beauty and the Beast (1934).

The notion that comedic business could occur during song delivery -- and wink to the audience that this was, after all, supposed to be amusing -- is light-years beyond the dire presentation of Avery's prior musical cartoon. Something important to Avery's comedic vision clicks into place with this cartoon.

The use of extreme foreground and background space is also unthinkable

in earlier Schlesinger cartoons. Avery often indulged in baroque visuals

in his Warner Brothers cartoons--much moreso than in his 1940s and '50s

work, in which the staging is as flat and blunt as possible.

Expressionism creeps into the nightmare conclusion of Abner's daydream. These screen grabs show off the limited color palette of the Congdon-styled backgrounds. It's important to consider that no color cartoon (to my knowledge) had ever attempted a consciously chosen color scheme before (Page) Miss Glory.

The general tendency was to run riot with whatever colors were available--3-strip IB Technicolor, or the two-color processes everyone else had to use before 1935. Aside from key colors for characters, which seldom strayed from a few standard hues, early color cartoons are often visual chaos. Not until the experiments of John Hubley, Chuck Jones and Shamus Culhane, in the early 1940s, would this notion of conscious styling to animation colors be approached.

Abner is jarred back into the glum reality of hicksville in a clever matched shot...

And then the long-awaited long black limousine arrives. A gallery of Avery-unit caricatures greets the oncoming car. Thanks to the always-great Thad K., I've managed to identify the people pictured...

From left to right: Virgil Ross, Melvin "Tubby" Millar, Bobe Cannon, Bob

Clampett, Tex Avery, Sid Sutherland, and Chuck Jones. Thad further

notes: "These look to be drawn in Clampett's own style as they match his

caricatures of the period."

A tug of the rug, at cartoon's end, was always an Avery stand-by. Miss Glory is no Norma Shearer; she's a lollipop-slurping, grating sub-Shirley Temple!Abner is so disappointed he faints into Miss Glory's candy-sticky arms. She is, of course, delighted, and just before iris out, she offers one of Avery's first contemporary pop-culture references--something the cartoon's 1936 audience would have instantly gotten. "Play, Don!"* she says, looking out past us, to the presumed studio orchestra awaiting the wave of her gooey baton:

* For those not steeped in 1936 American pop culture, the Don was Don Bestor, the bandleader of comedian Jack Benny's popular radio program. Like Avery, Jack Benny was fond of shattering the fourth wall between performer and audience. For all we know, Benny's doing so may have influenced Avery to bring this notion into the animated cartoon.

(Page) Miss Glory is a major step in Tex Avery's journey. Despite his dismissal of the cartoon, he achieved some important goals here. For the first time, he realizes the notion that all cartoon conventions are sitting ducks, ready to be rattled, inverted and subverted. This entertaining, genuinely funny cartoon proved that this could be done, within the context of satisfying the front office. This would be Avery's call to arms for the next couple of years.

UP NEXT: More irreverence for the Merrie Melodies with I Love To Singa!

The big takeaway from this cartoon is the tremendous discipline the Avery unit showed in putting across the art deco sequence, especially in contrast to the lumpy opening and closing scenes. The timing still isn't down here and the characters tend to 'float' in spots, but nobody outside of Disney up to this point had ever tried to stay focused on anything more than the basic character and background designs (i.e -- the Fleischers had to make Popeye, Olive and Bluto look like Elsie Segar's renderings, but they were completely free to design the secondary characters and backgrounds to the house style). Going by Avery's comments to Joe Adamson that Leon knew he had talent in Jones and Clampett, but "they didn't get along with the other units" it may be in part why Avery's unit was promoted above Jack King's -- once Tex showed he mashed with Chuck and Bob, it was clear their unit was the one with the skill to do a cartoon like this.

ReplyDeleteAlso, the cutting on empty martini glass gag is fast, but without any fast action being involved, which is also something new -- Avery respects the audience enough not to hold the gag for an extra 3-4 seconds to make sure we get it (and while the characters may also 'float' here, they're also supposed to be swacked out of their minds on gin and vermouth, so the tipsy 'floating' fits, and Avery's on to the Sally Rand scene a moment later).

The overhead Busby Berekly-shot with the circles is of course, a WB title reference! Bereneice Hansell is the little girl.Steve

ReplyDeleteAt the end of the day, I sorta wonder what Miss Congdon thought of the entire experience? I suppose her only reward was getting recognition for her work through simply getting her name (possibly her signature) printed boldly under the title the way the cartoon sets it up for the world to see. Whether she saw it once it was in the theaters or not I don't know, though I do wonder if she ever tried sticking that in her resume for potential employment after her college training? Was she happy with the film or was she taken back by something Avery & Co. did outside her settings alone? I suppose we'll never know, yet her name will live on simply because this cartoon ceased to become forgotten thanks to the approaching TV medium that kept it in the public eye for many years to come, whether Tex liked it or not.

ReplyDeleteAnd because I bother noticing these things, I find at least two entries for Leadora Congdon on Ancestry.com, though I can't access them since they want you to pay whatever membership fee I do not want to bother with, but there is a picture of her with a dog and says she was born in 1903 and died in 1965.

http://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?gl=ROOT_CATEGORY&rank=1&new=1&so=3&MSAV=0&msT=1&gss=ms_f-2_s&gsfn=Leadora&gsln=Congdon&uidh=000

Thoser New Yorker characters no doubt, in 1935, influenced the little Monolopy guy on the Monopoly board ("Monopoly" actually goes back almost as much..our Monolopy game's Chance cards have a 1936 copyright..)SC

ReplyDeleteLeadoah Congdon indeed was a polished artist..I knew her,... Albert Baynes Congdon, her father, was my step grandfather, my only grandfather...he was a peach...

ReplyDeleteLea and Teckie Osborn,from Lake Forest, Il.were dear soles.

I have her art.

Teckie jr.....if you are out there, contact me....

ELEANOR

See, this is why I wish people didn't post under 'Unknown" here. Now I'm dead curious to see her artwork if there's some way you could share these here or elsewhere, Eleanor. Please get back with me at sobieniak (at) hotmail (dot) com

DeleteI was just informed elsewhere that Teckie Jr. passed away in 2001. so if Eleanor can read this, please try to get in touch with me at the address I left above.

DeleteLeadora Congdon..the first female artist credited on an American cartoon, at least a WB cartoon, and the MAJOR CREDIT...Berenice Hanselle: the West Coast pseudo-Shirley Temple (later Shirley Temple Black)>:) SC Now I gotta page, PAGE miss Glory.

ReplyDelete