Release date: 9/13/1941

AVAILABILITY: On many dollar-store VHS tapes and DVDs, and online, usually in atrocious visual quality.

You can view a better-than-average version of this cartoon HERE, but be aware it contains an appalling stereotyped black character.

<><><><><>

The first Avery cartoon released without a director credit, All this and Rabbit Stew is the lowest moment in the screen career of Bugs Bunny. Never re-issued, for reasons obvious the moment the credits end, the cartoon was pillaged for gags in later WB cartoons. Like Bugs Bunny Nips the Nips (1944), it's a Bugs episode few have seen. The cartoon speaks well of no one involved, from the beloved series star to its writer and director.

Making peace with the racism rife in classic animation is a cross its historians have to bear. Baked into America's collective consciousness in the 20th century, racial and cultural prejudice is the bleak flipside of the nation's all-inclusive ideal. Wars were fought, lives were lost and ill will flowed through the country's veins as non-Anglo-Saxon people were thought of as less than human or "not as good as us."

I have lived for almost 60 years and seen racial prejudice ebb and flow in my country. It has disturbed me since childhood. It resurgence in this century is painful to witness. In my exploration of 20th century popular culture, I've confronted it every day of my life. It's hard to defend works that are worthy, aside from a lapse in humanity and grace that may last only seconds but leave a scar. The films of Tex Avery are loaded with such moments. It is a troubling aspect of a brilliant screen comedian and film-maker. And it doesn't bode well for the future of his work in the 21st century.

Avery wasn't alone in this stigma. I can't think of one Hollywood or New York cartoon studio from the classic period (roughly 1928-1955) that isn't riddled with racial stereotypes and cringy effigies of non-white culture. John Hubley, Chuck Jones, Friz Freleng, Shamus Culhane, George Pal, Bob Clampett and the Disney directors have films to their credit with regrettable moments of racial caricature and derision.

As writer Ruth Dubb notes in her essay "Racism in Animation:"

Were these men racist? Probably no more than the average person at the time. It would be more accurate to say that they took the easiest road in expressing themselves...while animation helped perpetuate negative stereotypes, it by no means originated it.

As writer Ruth Dubb notes in her essay "Racism in Animation:"

Were these men racist? Probably no more than the average person at the time. It would be more accurate to say that they took the easiest road in expressing themselves...while animation helped perpetuate negative stereotypes, it by no means originated it.

That "easiest road" was travel-worn by American popular culture in all avenues through the century. Much of this is junk (true for pop culture in general) and can be dismissed. The works of a great film-maker like Avery can't be shunted aside. Do we accept these misdeeds with the historian's remove? Or do we pretend they don't exist and close the book on them? The jury remains conflicted and hysterical. In a sense, we need these artifacts as a reminder to be better human beings. But how do we mitigate the ugliness of their worst moments?

Avery's 1948 M-G-M cartoon Half-Pint Pygmy is an example of the lush zenith of Hollywood studio animation. It contains a string of brilliant comedic ideas and an edgy, disturbing finale. But it also confronts the viewer with the likes of this:

Avery's 1948 M-G-M cartoon Half-Pint Pygmy is an example of the lush zenith of Hollywood studio animation. It contains a string of brilliant comedic ideas and an edgy, disturbing finale. But it also confronts the viewer with the likes of this:

Avery was perhaps the last Hollywood cartoon-maker to use black caricatures. The last example briefly mars one of his finest films, Magical Maestro (released February 9, 1952). Its use in this cartoon isn't as degrading as blackface gags in Garden Gopher (9/30/50) and Droopy's Good Deed (5/5/51).

The Droopy cartoon is a ferocious field-day of demeaning black gags. The Big Cartoon Database website logs the problematic moments (real and apparently imagined) of this seven-minute short:

"This is one of the most heavily edited cartoons on TV. In the version currently televised [at the time this was written], there are four major edits:

- Spike

getting struck by lightning, leaving him in blackface, fades out before

the audience can see the result.

- Droopy's

line, "Hey, Blackie, any more babes in there?", after the wooden

shack goes up in flames, leaving Spike in blackface, is cut.

- After

Spike sees Droopy run out of the burning cabin carrying a blonde lady in

his arms, Spike runs into the same burning cabin and comes running out

with a black lady in a red dress, red lipstick and gold hoop earrings.

- The

scene in which the rich gentleman rewards Spike for returning his hat by

handing Spike a seemingly endless stream of cash is trimmed. The two are

blown up by a bomb, which was planted by Spike himself earlier during the

scene. Originally, the two were transformed into black caricatures in

tattered clothing. The rich man's cultured voice ("10, 15,

20...") turns into a stereotypical black voice who proclaims

"...eleventy billion...and two bits!", throwing torn pieces of

money in the air. On TV, the scene now ends as the bomb explodes".

That Komorowski calls BS on one of the claims listed in the above quote, and states:

"There was no black lady in Droopy's Good Deed. Total bullshit started by some head-case back on the old GAC forum."

(Those curious may examine this rescued post from the old GAC forums, which I should have remembered, but didn't. Life does get in the way of animation, you know. I strive for accuracy in whatever historial info I present here, and, being human, I fail from time to time. Anyhow, enough of this. Back to cases.)

Some of these bits remain in existing versions. In the latter part of the 20th century, many classic cartoons with ethnic gags were shown on TV. The gags were embedded deep in the cartoon, and TV stations couldn't care less and took no action unless an upset viewer complained.

"There was no black lady in Droopy's Good Deed. Total bullshit started by some head-case back on the old GAC forum."

(Those curious may examine this rescued post from the old GAC forums, which I should have remembered, but didn't. Life does get in the way of animation, you know. I strive for accuracy in whatever historial info I present here, and, being human, I fail from time to time. Anyhow, enough of this. Back to cases.)

Some of these bits remain in existing versions. In the latter part of the 20th century, many classic cartoons with ethnic gags were shown on TV. The gags were embedded deep in the cartoon, and TV stations couldn't care less and took no action unless an upset viewer complained.

M-G-M has the worst track record of offensive material in their catalog. Their most popular cartoon series, "Tom and Jerry," has a stereotyped black maid in several entries. Voiced by Lillian Randolph, the character's face is never seen long enough to register, and Randolph's vocal performance brings a warmth to the proceedings that is almost too seductive.

I don't know enough about Avery's personal beliefs to deem him a racist. His life's work is marred with unfortunate moments. The cartoon we're about to examine is perhaps the most lamentable of his career. It's not a great cartoon by any standard. Were the antagonist white, it would still fall flat. One brilliant gag sequence was, in a stroke of irony so common to Hollywood animation, used in a later Warner Brothers cartoon maudit, 1946's The Big Snooze, abandoned by director Bob Clampett when he parted ways with Leon Schlesinger.

After this credit card, which has more space due to no named director, the first thing we see is this:

This image, aside from its racial caricature, tells us something about this character, and the main reason this cartoon doesn't work. It's fun to see Bugs Bunny annoy white, privileged, entitled Elmer Fudd. Ditto for aggressive, arrogant and self-destructive Yosemite Sam. They are, for all their differences, on the same plane: they need to be taken down a peg.

This guy is not hunting for sport, or acting out some demented pirate/cowboy fantasy. He is a poor, timid soul who is hunting out of need. He's a reluctant hunter, as witnessed by the way he drags his shotgun behind him. This is not his preferred activity, but unseen forces outside this cartoon (hunger, family needs, financial woes) have forced him to take action and bag something for the dinner table. He is not a fit adversary for the likes of Bugs Bunny.

Like Tortoise Beats Hare, this was an experiment with a promising new character, which Bugs still was in 1941. Unlike the earlier film, this what-if bears bitter fruit and misuses Bugs as completely as A Wild Hare defined him.

With this cartoon, we see Avery beginning to not care about his characters. No one is likable in this film. They're less characters than chess pieces. Avery will perfect this directorial distance at M-G-M, where he was already at work on his first picture there, The Early Bird Dood It, before this cartoon saw general release.

Back to the film. Our nameless woodsman encounters the usual totems of Bugs' presence: rabbit tracks; rabbit hole.

Avery delayed Bugs' visible entrance in A Wild Hare, and this variant is clever enough. Bugs gives hunter his standard what'supdoc line...

Meanwhile, our hunter frees himself from his hat and seeks revenge--and his rifle.

This next gag gets bonus points for not using the obvious pinball metaphor that seems set up by the background art.

Back to the predator/prey conflict. Here's where material you're familiar with, via The Big Snooze, begins. (In the maudit-Clampett cartoon, which you can reference HERE, the footage starts at 00:38.)

Bugs makes a peculiar (and, I'd imagine, insulting) gesture with his hand and chin to provoke the hunter to reaction. Whatever this gesture is, it had fallen out of fashion by the time I was a kid.

Bugs' grin betrays his malevolent glee. As his character refined, an outward cool masked the enjoyment he often got from besting his foes.

On the third go-round (the golden comedy Rule of Threes), the log becomes animatable and Bugs reverses its direction. Hunter is locked into the circular chase, which gravity obliges for a moment.

The exaggerated brushwork on the hunter's feet lends credence to the futility of it all.

He turns to face his ex-foe, stripped bare of all pride, dignity and place in the world. The look on his face is saddening.

After this credit card, which has more space due to no named director, the first thing we see is this:

This image, aside from its racial caricature, tells us something about this character, and the main reason this cartoon doesn't work. It's fun to see Bugs Bunny annoy white, privileged, entitled Elmer Fudd. Ditto for aggressive, arrogant and self-destructive Yosemite Sam. They are, for all their differences, on the same plane: they need to be taken down a peg.

This guy is not hunting for sport, or acting out some demented pirate/cowboy fantasy. He is a poor, timid soul who is hunting out of need. He's a reluctant hunter, as witnessed by the way he drags his shotgun behind him. This is not his preferred activity, but unseen forces outside this cartoon (hunger, family needs, financial woes) have forced him to take action and bag something for the dinner table. He is not a fit adversary for the likes of Bugs Bunny.

Like Tortoise Beats Hare, this was an experiment with a promising new character, which Bugs still was in 1941. Unlike the earlier film, this what-if bears bitter fruit and misuses Bugs as completely as A Wild Hare defined him.

With this cartoon, we see Avery beginning to not care about his characters. No one is likable in this film. They're less characters than chess pieces. Avery will perfect this directorial distance at M-G-M, where he was already at work on his first picture there, The Early Bird Dood It, before this cartoon saw general release.

Back to the film. Our nameless woodsman encounters the usual totems of Bugs' presence: rabbit tracks; rabbit hole.

Evidence of occupant: discarded carrot butts.

In a clever topper, Bugs apparently eats the green part of the carrot by mistake;

realizes error and retrieves legume.

And here's where our heartaches begin.

Bugs hiccups from his carrot orgy. Hunter offers "Gesundheit..."

...and realizes he's blown his cover.

Fuddsian aggression activates Bugs into seeming submission.

We know better, but the hunter doesn't.

In a small moment of inspiration, Bugs' rabbit hole moves stage left. Hunter follows...

...and hole transmutes into a tree.

In medium-shot, hole is now a painted aperture. This doesn't faze the hunter, who opens fire.Avery delayed Bugs' visible entrance in A Wild Hare, and this variant is clever enough. Bugs gives hunter his standard what'supdoc line...

Hunter does his spiel...

...and Bugs, who has in no way addressed the ethnicity of the hunter, does something telling. Instead of the kiss of humiliation, which he bestows freely on Elmer Fudd, he pulls the hunter's sporty hat down over his head. It might have been a no-no for Bugs to kiss this person of color.

Bugs does an odd variant on his comedic escape.

The swimming-through-dirt concept doesn't work, as it causes the viewer to defy this strain on cartoon logic. It's over quick enough, but it's one experiment that fails.Meanwhile, our hunter frees himself from his hat and seeks revenge--and his rifle.

He finds his firearm via some Buggsian aid.

This routine was hard-wired into the Bugs canon: a little touch of John Steinbeck's Lennie is referenced as hunter, oblivious, asks his prey where he's gone.

These loose-limbed poses are delightful; as still images, they teem with life.

Hunter's loose-limbed running cycle is a thing of beauty,

The light of reason dawns on this poor soul.

He suffers the transition to wrapped lollipop--exposing his status for all to see.

His response is righteous anger. He's likely felt that sucker transition hundreds of times in his life.

Camera follows his line of vision and leads us to Bugs.

Bugs is in play mode.

With the aid of a plumber's friend, our hunter attempts capture-by-suction.

Bugs uses the hat-pull substitute and then tickles his would-be predator.

Avery tries out another iffy sight gag while the plunger is still affixed to Bugs' rear.

A final humiliation before this odd experiment--a strike of contempt with plunger handle.

This run cycle is odd but not amusing. It shows Avery's boredom with the restriction of the Bugs Bunny formula, and a desire to do something--anything--to vary the proceedings. Were this cartoon a more socially acceptable Bugs v. Elmer episode, it would still feel like a strained place-holder.

Before the hunter can grab the plunger handle, a surprising switcheroo has happened.

The surprise of the skunk is a small triumph of comedic timing and table-turning.

Hunter has found another being who's lower on the social circle than himself.

He takes steps to protect his thin wisp of status.

Bugs waves and does an amusing buck-and-wing into a cave.

Horizontal flip of that loosey-goosey run cycle,

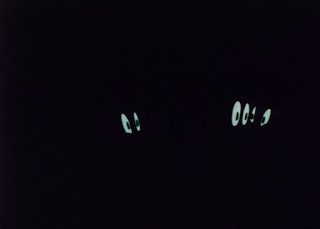

We know there's a third party in the darkness. Avery did this eyes-only comedy well, and its sharp timing is a welcome respite.

This tennis-match comedy leans on the voice artists, but works well enough.

Hunter's double-checking, as his brain comes to a grim conclusion, is a clever touch.

The inevitable lighted match reveals...

Avery will return to this set-up in the aforementioned Half-Pint Pygmy.

In both cases, protagonist and antagonist jet out of cave...

This bit is a nice topper, with an unexpected finale that also provides visual evidence of Avery's hand in the tag-team cartoon maudit, Wabbit Twouble.

That Avery-model bear appears in Wabbit Twouble, and is an aid in determining what part of the cartoon was mapped out by Avery, pre-expulsion, and what was added by Bob Clampett, who opted to take full credit for the film.

I will cover Wabbit Twouble in this blog, but Thad Komorowski and Bob Jaques devoted an episode of their must-hear podcast Cartoon Logic on this film. Have a listen HERE (and subscribe!!).

In crisis, hunter and hunted become one for an unconscious moment.

This moment is a relief, and is well-handled.

It's a nice change to see Bugs' slow reaction to the inevitable...

...although Avery didn't yet realize that his audience-identification characters shouldn't do wild takes. He violates this tacit rule three times in this picture. To be fair, he hadn't refined the rules to this extent in 1941.

There's one now.

Buckshot becomes comedy diagram (as will bees and other grouped traveling objects in Hollywood studio cartoons).This next gag gets bonus points for not using the obvious pinball metaphor that seems set up by the background art.

A welcome switch to another set-up occurs as this bit grows thin on the viewer.

Yes, Virginia, there is a payoff.

Many Hollywood cartoons look like they take place on a golf course. Those manicured landscapes, with their vast skies and barren green plains, are a visual icon of the animated film. Avery makes concrete this unspoken link--and gets a laugh out of it!

This diagram-comedy has worn out its welcome, but it persists...

Let's get that skunk back in the picture.

...or skunk. There appears to be missing dialogue (probably garden-variety gibberish) on the soundtrack.Back to the predator/prey conflict. Here's where material you're familiar with, via The Big Snooze, begins. (In the maudit-Clampett cartoon, which you can reference HERE, the footage starts at 00:38.)

Bugs makes a peculiar (and, I'd imagine, insulting) gesture with his hand and chin to provoke the hunter to reaction. Whatever this gesture is, it had fallen out of fashion by the time I was a kid.

And here is the cartoon's lone moment of real inspiration. The timing and delivery of this literal table-turning bit is so good that whomever completed Big Snooze (Art Davis, if memory serves) only had to have the animation re-painted--and, of course, Elmer Fudd substituted for this film's antagonist...

The routine is set up to establish a rhythm (and the viewer's expectation that results)

so that it can be messed with...

ANIMATION LAW: When an object is suddenly on a cel, you know the stakes have changed.Bugs' grin betrays his malevolent glee. As his character refined, an outward cool masked the enjoyment he often got from besting his foes.

On the third go-round (the golden comedy Rule of Threes), the log becomes animatable and Bugs reverses its direction. Hunter is locked into the circular chase, which gravity obliges for a moment.

Carl Stalling uses the five-note "sucker" theme as metamorphosis occurs.

Hunter scrambles for false safety.

Second verse, same as the first (tho' a bit quicker).

Hunter goes through log, now part of the background and lengthened a la the Avery Limo. Camera pans left for a good while.

Hunter touches earth and feels around to be sure he's someplace solid.

Bugs emerges, delighted, and this sort-of sequel to the falling finale of The Heckling Hare hits its trifecta.The exaggerated brushwork on the hunter's feet lends credence to the futility of it all.

Flop sweat.

A final check, just...in...case...

All hopes dashed. Going down!

Bugs' cringe as hunter meets earth adds to said impact.

Rabbit delivers standard "joik had it comin' to 'im" aside.

From Michael Barrier's Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in its Golden Age (Oxford Univ. Press, 1999), p. 412:

"Aesthetic conflict surfaced in Avery's cartoons not through a violation of the body, but as a violation of style...(a)t one point in (this cartoon). Bugs registers surprise by literally going to pieces: his arms, legs and head seperate from his torso, even though there has been until this point no suggestion that the characters' bodies are not flesh and blood...it was rare...for Avery to announce so openly that his ideas about comedy weren't wholly compatible with the kind of animation he had welcomed into his films."

This feels like a declaration that Avery no longer cares about his characters as tangible, relatable icons of life. This moment is the extreme away from "The Disney Way." It's jarring, and is something no other director of Bugs did to this extreme. As Bugs' personality solidified (and via the Bugs cartoons directed by Chuck Jones in the last half of the decade), his character is too cool to physically react, beyond smaller gestures of surprise, confusion or amusement.

The alienation rife in this moment--it doesn't feel "right" in the context of Bugs as we know him, after all his significant films are part of animation's canon--is perhaps the most important thing about All This and Rabbit Stew. It isn't dwelled on; as I've composed these thoughts, the rest of the cartoon could have played out. But it is a lone virtue of a disappointing and unlikable cartoon.

Bugs has harangued, humiliated and caused harm to this downtrodden outsider who is only hunting because he has to. His goose appears cooked and ready to serve.

The skilled negotiator, Bugs moves the shotgun barrel away from his chest, urges the hunter to relax, and reaches into his "pocket" for the incident that earns this film its exhibit in the Hollywood Hall of Shame.

Something rattles in Bugs' palm. He lures the hunter from breathless rage to rapt curiosity.

"What y'all got there, man? It couldn't be a pair... of...them..."

Bugs' smugness is cringe-inducing...

...as is the reveal. Curious that the word "dice" isn't spoken. The act itself, which is manipulative and contemptuous on Bugs' part, is A-OK, but calling them dice apparently wasn't.

Anyhow, this happens.

Hunter escorts ex-prey to convenient bush to play.

This is a budget-friendly climactic action. Short cycles of the characters' hands and arms are all that's needed, as the voice track does the heavy lifting.

A jazzy theme with hints of "Blues in the Night" accompanies this hidden game.

(The song is "What's the Story, Morning Glory?" according to Devon Baxter.)

Hunter's luck fails him. It's hard to prepare one's self for what comes next. It's the most shocking moment of Bugs Bunny's long and storied career:

Bugs, in hunter's clothes, does a mocking parody of that poor soul's entrance speech. Anger comes over the rabbit's face, and he sticks out his tongue as if the mimicked words are poison.He turns to face his ex-foe, stripped bare of all pride, dignity and place in the world. The look on his face is saddening.

Camera whips left to see the cause of Bugs' shock.

"Well, call me Adam," the hunter says, showing that his sense of irony still remains,

and he's willing laugh the whole thing off as a bad day.

The iris is not sacred in Avery's universe.

The wee bit of safety the hunter might feel...

...is violated by Breitbart-Bugs (TM).

He had to do it. If only for sheer malice.

Bugs gloats at us as the miserable thing fades to black.

A tolerable cartoon for its first five minutes, despite the burden of "Tex's Coon," as the hunter was dubbed on an infamous model sheet (referenced in Barrier's book), All This and Rabbit Stew reveals two levels of apparent contempt: towards the cookie-cutter format of the predator/prey scenario and towards non-white human beings. The first level is most pervasive. This is the roadmap for the rest of Avery's career in theatrical cartoons. Not caring about the characters was Avery's prima facie for getting the freedom to make the impossible happen before our eyes.

In Avery's best cartoons, the outlandish is made tangible and vice versa. We laugh at the absurdities, exaggerations and fourth-wall damage done in his films. But a little bit of the shock of the new still remains, after close to a century's remove. Directors like Chuck Jones and John Hubley defended their right to have audiences concerned about their animated characters. Jones' Bugs succeeds because we like him and relate to him. The characters in Hubley's UPA shorts have a similar appeal. We want to stick around and know them better. This could come at the expense of comedy, but it's a big part of why these cartoons remain universally admired.

Avery, by 1941, was done with that. He considered it baggage that weighed down his concept of an ideal comedic universe. At M-G-M, he had a decade or so to realize that vision, over and over, in rousing triumphs and abject failures. He continued to take chances and resist formula, even when it was demanded of him. That conviction is admirable.

As said at the start of this post, I don't know Avery's attitudes towards black lives. He was a good ol' boy, and it would have been impossible to escape racial intolerance in his childhood and young adulthood. He may have used racial images to shock the viewer. Avery lived to jolt his audience with images, moments and characters that scraped a raw edge away from the comfortable norms. That he did this at the most escapist film studio of Hollywood's golden age, and with the biggest budgets outside of the Disney empire, is remarkable. I cannot defend, excuse or explain away Avery's depiction of non-whites in his work. It is a component of the most brilliant animation resume of them all, in my opinion, and it is as bracing and discomfitting as the wildest, weirdest concepts in the films themselves.

Spending several hours of study on this cartoon hasn't been pleasant for me, but it had to be done as part of my study of these important early works of animation's greatest director. I am thankful to have it over and done, and I am curious to hear what you think about this cartoon--and about the use of racial caricature in Tex Avery's work.

Special thanks to Devon Baxter, who does me the huge favor of capturing screenshots of these cartoons. Devon is doing phenomenal work in animation history and film preservation. Please visit his Patreon page HERE.

PS: All This and Rabbit Stew was enthusiastically reviewed in the film-trade magazine The Exhibitor's 9/17/41 issue. This unsigned review, provided by animation historian Don Yowp (thank you Don!) names the hunter "Sambo"--a name the character would retain in his appearances in Dell Comics' Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies comic book. Thad K reminded me of a walk-on appearance in an "Elmer" story in issue #21. Here is "Sambo"'s guest appearance on two successive pages:

UP NEXT: Back to the spot-gags with Bug Parade.

In my opinion, Bugs Bunny Nips The Nips is much worse, because it's a blatant assault on a race and culture and that it also contains racial slurs. But, All This And Rabbit Stew comes very close and is arguably one of the worst ones on the fabled Censored Eleven list (along with Angel Puss). The gag with the rabbit hole, the bullets taking on a life of their own, and Bugs flying apart are the only redeeming bits of comedy. The top notch personality animation by (I presume) Rod Scribner of Bugs and the hunter that sets up the craps game is cringeworthy to watch. I presume that the choice of musical score also has racial connotations.

ReplyDeleteI've never wanted to accept the idea that my heroes in animation were racist, but I've settled for the fact that they lived in an entirely different era and that their perspectives possibly evolved over the years. (I've kind of wondered if the directors were ever aware of the censored eleven list and what they may have had to say of their entries in later years, aside from Clampett who discussed the backstories of his own entries).

I don't agree with the idea of suppressing these films entirely (at least for us more mature film and history buffs), but at the same time I can understand why the distributors would have serious concerns of perpetrating negative, antiquated racial views in the current political climate.

THe Japanese in WWIIm, though had bombed Pearl Harbor, while the African Americans hadn't, so that would also put BBNtN's in context. We DO get the famed log gag used,

DeleteThe hunter character also appeared briefly in the Looney Tunes comic books (which started around the same time.) There, he was known as “Sambo”, and he had the same racist “Stepin Fetchit” mannerisms...at one point referred to as a “Wazy colored boy” by Elmer Fudd. Yikes! Some people believe that this character and the one in Chuck Jones’ “Angel Puss” are one and the same.

ReplyDeleteI think I blanked out on the character's use in the comic books. Of course, they'd pick him. Sigh. And he does look much like the "Angel Puss" kid. Again, sigh.

ReplyDeleteJoe Adamson's 1975 book on Avery only mentions ATARS in passing, and notes that the cartoon was purportedly rotoscoped to replace the black hunter with Elmer. Obviously, it was only the log sequence where the rotoscoping occurred, but you could see why Adamson would include the statement, because while the hunter does Stepin' Fetchit-like stereotyped actions Fudd would never do, none of the gags until the very final scene are reliant on the audience knowing about the stereotype about blacks and dice.

ReplyDeleteThe end gag, in fact, seems to be the entire reason the hunter's in there instead of Elmer. But after making the gags faster and faster as the cartoon went on, the momentum stops dead after Bugs' break-apart take, and we're treated to the near-static shot of a bush, mixed in with dice sounds and Mel's voices (the lack of animation might have made Leon happy budget-wise, but it violated one of the boss' few desires for his cartoons, which was a fast finish followed by the fast closing music). And Bugs' contempt for his adversary at the iris out recalls Avery's misfire in "The Haunted Mouse", where Tex's ghost rodent anger and contempt makes for a mostly-joyless seven minutes of torturing his dumb adversary (at least Bugs doesn't spend the entire cartoon sneering here, but the meanness of the closing gag sort of proved Friz Freleng's later reasoning on why he preferred to work with Yosemite Sam than with Elmer, because Bugs worked best when he had a strong adversary to play against, and that audiences could almost feel sorry for Fudd for all the things the rabbit puts him through. That's even more the case at the end of this cartoon).

Well, the Japanese of the era as attacked here HAD bombed Pearl Harbor, though,

DeleteI'm not sure the hunter is dragging his gun because of reluctance to go hunting. I think it might be a bit of Stepin Fetchit laziness. I do like this analysis though.

ReplyDeleteSorry to refute your claims That Komorowski. But I myself did see that black lady scene play out just as was described. I was so surprised back then that I jotted what I saw down on paper. Spike ran into that log house after droopy retrieved a blonde and ran out, then he runs in and he gets a black lady and carried her to safety. You could even hear the music track was cut on the common broadcasts missing that array. Someone will stumble upon a surviving film I am sure. JW

ReplyDelete