DVD-Blu-Ray Availability: none

If you would like to see a nice print of Lewis Milestone's 1939 film (discussed in-depth here), click HERE to download it. Thanks to Devon Baxter for supplying this unusually nice version of a film lost in PD limbo.

<><><><><><><><><><>

The Avery unit's last cartoon of 1940 was inspired by the 1939 Hal Roach-produced film of John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men. Directed by Lewis Milestone, who helmed films as dissimilar as All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and Ocean's 11 (1960), the movie, for its pastoral settings, is a fore-runner to the film noir sensibility. Its main characters, George and Lennie, are pre-destined to suffering, trouble and tragedy. They first appear in Milestone's version two steps ahead of a lynch mob, running for their lives and hopping a freight train to temporarily escape death.

We next see them aboard a bus, and the characters and their relationship are deftly established. George Milton (played by Burgess Meredith) is a confident, world-weary know-it-all. Had his life circumstances been better, George might have been a wheeler-dealer. Instead, he's an itenerant laborer saddled with Lennie Small (Lon Chaney, in a breakout role that should have led to bigger things, but never really did).

Lennie was described by a junior high school classmate, c. 1975, as a "ree-tard." He was sent to the principal's office for this outburst, which was too much by '70s standards [altho' racial and cultural epithets were still alive and well in American pop culture] and, I presume, chastened for this statement.

Lennie has issues; due to a traumatic head injury, he lacks the ability to reason and remember. He's eerily reminiscent of a person with Alzheimer's. Save a few strong memories, Lennie can't hang onto to any event for more than a few minutes. We see him have a distressing moment. He reaches in his front shirt pocket for his work permit, can't find it, and panics. Easygoing George reassures him; he's got both their permits. Would he, for a minute, entrust Lennie with such an important slip of paper?

George and Lennie are 86d from the bus by a vexed driver (played, uncredited, by Eddie Dunn, a veteran actor and a familiar face from Hollywood Westerns and occasional classic films like The Great Dictator and The Bank Dick) and face a 10-mile walk, under the merciless California desert sun, to the ranch where they'll strain their bodies hoisting bags of grain in exchange for three hots and a cot.

They decide to camp out in a wooded area. There, George forces Lennie to hand over a dead bird, which he heaves away in disgust. Lennie likes to pet small animals--it obviously calms his general sense of ill-being. George complains about having had to take away a dead mouse a few days earlier.

After their meal of canned beans, Lennie exhorts George to repeat a favorite fantasy: that, someday, the two of them will settle down, and be well-off. They'll have a small farm of their own, and Lennie will have the job of taking care of the rabbits. "Tell me about the rabbits, George," Chaney's Lennie says, with all the hope in the world showing in his glazed, innocent eyes.

It's almost impossible to watch Of Mice and Men without a layer of irony. It's a fine movie, but it has been the source of so much parody that it's corrupted to all but those who haven't yet been exposed to the spoofs. And Tex Avery is the man responsible for turning Steinbeck's Depression-flavored tragedy into a byword for morbid farce. Something in the George and Lennie relationship--and in the way Lon Chaney Jr. plays Lennie got to Tex Avery--it dug in and wouldn't let go.

At M-G-M, his fondness for the dark-comedy potential of Of Mice and Men manifested in a three-film series starring two bears, George and Junior. The title card to the first cartoon in the series, Henpecked Hoboes (1946), is done in an allusion to the Milestone movie's credits.

As with the cartoon I'll eventually discuss today, the "Lennie" character is lovingly voiced by Avery. His rendition inspired some imitations at Warner Brothers and made the "Lenny" character an icon of sick comedy.

Robert McKimson's take on the duo, seen in 1953's Cat-tails for Two (the cartoon that introduced the regrettable Speedy Gonzales) has a particularly funny "Benny" by Stan Freberg; Art Davis' Dough Ray Me-ow (1948) offers a Blanc Lennie-style performance more like his later "idiot" voice, which America loved when it was modified to suit the character of Barney Rubble on The Flintstones. There's a faint touch of Chaney in the mix. Friz Freleng, for reasons unknown to me, did a sort-of remake of today's cartoon--with footage cribbed from the opening of the 1940 original--for the uneven Foxy by Proxy (1952), which has more Freberg "Lennie" action, if little else to recommend it.

To us TV kids of the 1960s and '70s, doing the "Lenny" voice was an instant laff-getter on the playground. Pet lines such as "Which way did he go, George?" and "Tell me about the rabbits, George" would lay 'em in the aisles.

Of Mice and Men is not humorless, though it is a bit preachy. It walks the fine line between tragedy and comedy. John Steinbeck was an anecdotalist and keen observer of human behavior. He was drawn to personas like George and Lennie; things happened to them because they happened to be there.

Lennie Small's fixation on rabbits, puppies and other soft furry animals is super-charged in Chaney's film version. Chaney's nuanced performance has hysterical and heated moments. He gets deep into Lennie's persona, and his wide-eyed excitement and confusion is intense. We often laugh when we don't know what to do with hard-to-process behavior or information. Lennie is too large (in physique and presence) to ignore, and his differently-abled babble sometimes challenges the viewer to keep a straight face.

Chaney particularly shines in a long scene where he encounters Crooks, a black worker ostracized from the whites who has taken to reading to fight his loneliness and suppression. Played by Leigh Whipper, Crooks is initially resentful to the invasion of his privacy, but he connects to Lennie as a fellow outcast, despite their great differences. Chaney gets across that his Lennie doesn't really understand the racial dilemma--he's just happy to have someone to talk at while George is in town on a Saturday night.

The film was critically acclaimed and nominated for three Oscars (two for composer Aaron Copland and one for Hal Roach stalwart Elmer Raguse), but it didn't do well at the box office, perhaps due to its subject matter and the overall darkness of its story.

How did Fred Avery respond to Of Mice and Men, when he saw it in its original theatrical run of early 1940? The film made an obvious deep impression, and added a new element to his comedic schemes. Was he engrossed by Lewis Milestone's apt direction in the pre-credit sequence, roused by the Copland score and then, perhaps, did he catch himself chuckling when the twanging of a jaw harp enters the film, as the fugitive pair nab a ride on a hobo-filled boxcar?

Or was it during that scene on the bus--which establishes Lennie's short-term memory issues, and suggests their inherent comedy? Perhaps it was the scene in the woods, with the confiscated bird carcass and Lennie's glee at the fantasy of rabbit care. Oh, to have been a witness to that moment in some Los Angeles movie house--Avery's tell-tale laugh punctuating the solemn dark of the theater.

Of Fox and Hounds is the first fruition of Avery's fixation with the Steinbeck tragi-agri-comedy. This was another revolutionary concept thrust into the film world--one that didn't have as high an impact as Daffy Duck or Bugs Bunny, but came mighty close.

It's a template for the soon-to-be standard Bugs Bunny cartoon, although the rabbit is nowhere in sight. Prey, vastly out-witting its predator, plays along, either for the underdog's pleasure in besting its alleged superior, or because it's a slow day and it beats taking a nap. Mel Blanc's voicing as the fox is mostly Bugs with some subtle differences. Some of Blanc's natural speaking voice comes through, as it seldom did when he inhabited the Bugs character.

Avery's first take-away from Steinbeck was that a character with short-term memory is endlessly funny. Thus, he takes the license, as Joe Adamson comments in his seminal book Tex Avery: King of Cartoons, to do the same big gag sequence three times in a row--and make us laugh along with him. Part prank on the viewer and part comedic discovery, the structure of Fox and Hounds is a stroke of genius.

Avery never lost the knack for creating introductions that almost convince you he's serious. The introduction to this cartoon, with its breaking-dawn atmosphere, stylized landscapes and rotoscoped animation of the human form, deliberately sets up a decorum so it can be broken. One of Carl Stalling's pet pieces, a movement from The William Tell Overture, helps further this mood of no-kidding-folks.

Willoughby has a remarkably odd run-cycle, which will get maximal use in this longer-than-average Warner Brothers cartoon.

This physics-defying run cycle. bolstered by a zany Stallings cue, sustains through a dissolve to another part of the woods. Much time has elapsed via that dissolve. After a few lopes, Willoughby informs us that he's a regular expert on these woods.

Bugs inquires about a short cotton tail with Elmer; George displays his magnificent "long, bushy tail."

The bear's stunned reaction is a thing of beauty. Like Willoughby, he searches all around him, unable to yet feel anger at this bodily disturbance.

...and coaxes George out of the kennel, where he's apparently been staying for awhile. All emnity forgotten in Willoughby's head. George is a friend. For Avery, this is sentimental stuff.

A long silence is barely punctuated by a ping. The camera trucks down the cliff, much faster this time, to reveal the lack of crash and burn SFX...

I'd love to know how those mattresses got there. Perhaps a lot of time elapsed when "came another day."

|

| Lon Chaney, Jr. and Burgess Meredith in roles of a lifetime |

Lennie was described by a junior high school classmate, c. 1975, as a "ree-tard." He was sent to the principal's office for this outburst, which was too much by '70s standards [altho' racial and cultural epithets were still alive and well in American pop culture] and, I presume, chastened for this statement.

Lennie has issues; due to a traumatic head injury, he lacks the ability to reason and remember. He's eerily reminiscent of a person with Alzheimer's. Save a few strong memories, Lennie can't hang onto to any event for more than a few minutes. We see him have a distressing moment. He reaches in his front shirt pocket for his work permit, can't find it, and panics. Easygoing George reassures him; he's got both their permits. Would he, for a minute, entrust Lennie with such an important slip of paper?

George and Lennie are 86d from the bus by a vexed driver (played, uncredited, by Eddie Dunn, a veteran actor and a familiar face from Hollywood Westerns and occasional classic films like The Great Dictator and The Bank Dick) and face a 10-mile walk, under the merciless California desert sun, to the ranch where they'll strain their bodies hoisting bags of grain in exchange for three hots and a cot.

They decide to camp out in a wooded area. There, George forces Lennie to hand over a dead bird, which he heaves away in disgust. Lennie likes to pet small animals--it obviously calms his general sense of ill-being. George complains about having had to take away a dead mouse a few days earlier.

After their meal of canned beans, Lennie exhorts George to repeat a favorite fantasy: that, someday, the two of them will settle down, and be well-off. They'll have a small farm of their own, and Lennie will have the job of taking care of the rabbits. "Tell me about the rabbits, George," Chaney's Lennie says, with all the hope in the world showing in his glazed, innocent eyes.

It's almost impossible to watch Of Mice and Men without a layer of irony. It's a fine movie, but it has been the source of so much parody that it's corrupted to all but those who haven't yet been exposed to the spoofs. And Tex Avery is the man responsible for turning Steinbeck's Depression-flavored tragedy into a byword for morbid farce. Something in the George and Lennie relationship--and in the way Lon Chaney Jr. plays Lennie got to Tex Avery--it dug in and wouldn't let go.

At M-G-M, his fondness for the dark-comedy potential of Of Mice and Men manifested in a three-film series starring two bears, George and Junior. The title card to the first cartoon in the series, Henpecked Hoboes (1946), is done in an allusion to the Milestone movie's credits.

As with the cartoon I'll eventually discuss today, the "Lennie" character is lovingly voiced by Avery. His rendition inspired some imitations at Warner Brothers and made the "Lenny" character an icon of sick comedy.

Robert McKimson's take on the duo, seen in 1953's Cat-tails for Two (the cartoon that introduced the regrettable Speedy Gonzales) has a particularly funny "Benny" by Stan Freberg; Art Davis' Dough Ray Me-ow (1948) offers a Blanc Lennie-style performance more like his later "idiot" voice, which America loved when it was modified to suit the character of Barney Rubble on The Flintstones. There's a faint touch of Chaney in the mix. Friz Freleng, for reasons unknown to me, did a sort-of remake of today's cartoon--with footage cribbed from the opening of the 1940 original--for the uneven Foxy by Proxy (1952), which has more Freberg "Lennie" action, if little else to recommend it.

|

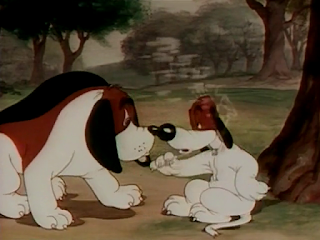

| George and Junior in Hound Hunters (1947). |

Of Mice and Men is not humorless, though it is a bit preachy. It walks the fine line between tragedy and comedy. John Steinbeck was an anecdotalist and keen observer of human behavior. He was drawn to personas like George and Lennie; things happened to them because they happened to be there.

Lennie Small's fixation on rabbits, puppies and other soft furry animals is super-charged in Chaney's film version. Chaney's nuanced performance has hysterical and heated moments. He gets deep into Lennie's persona, and his wide-eyed excitement and confusion is intense. We often laugh when we don't know what to do with hard-to-process behavior or information. Lennie is too large (in physique and presence) to ignore, and his differently-abled babble sometimes challenges the viewer to keep a straight face.

Chaney particularly shines in a long scene where he encounters Crooks, a black worker ostracized from the whites who has taken to reading to fight his loneliness and suppression. Played by Leigh Whipper, Crooks is initially resentful to the invasion of his privacy, but he connects to Lennie as a fellow outcast, despite their great differences. Chaney gets across that his Lennie doesn't really understand the racial dilemma--he's just happy to have someone to talk at while George is in town on a Saturday night.

The film was critically acclaimed and nominated for three Oscars (two for composer Aaron Copland and one for Hal Roach stalwart Elmer Raguse), but it didn't do well at the box office, perhaps due to its subject matter and the overall darkness of its story.

How did Fred Avery respond to Of Mice and Men, when he saw it in its original theatrical run of early 1940? The film made an obvious deep impression, and added a new element to his comedic schemes. Was he engrossed by Lewis Milestone's apt direction in the pre-credit sequence, roused by the Copland score and then, perhaps, did he catch himself chuckling when the twanging of a jaw harp enters the film, as the fugitive pair nab a ride on a hobo-filled boxcar?

Or was it during that scene on the bus--which establishes Lennie's short-term memory issues, and suggests their inherent comedy? Perhaps it was the scene in the woods, with the confiscated bird carcass and Lennie's glee at the fantasy of rabbit care. Oh, to have been a witness to that moment in some Los Angeles movie house--Avery's tell-tale laugh punctuating the solemn dark of the theater.

Of Fox and Hounds is the first fruition of Avery's fixation with the Steinbeck tragi-agri-comedy. This was another revolutionary concept thrust into the film world--one that didn't have as high an impact as Daffy Duck or Bugs Bunny, but came mighty close.

It's a template for the soon-to-be standard Bugs Bunny cartoon, although the rabbit is nowhere in sight. Prey, vastly out-witting its predator, plays along, either for the underdog's pleasure in besting its alleged superior, or because it's a slow day and it beats taking a nap. Mel Blanc's voicing as the fox is mostly Bugs with some subtle differences. Some of Blanc's natural speaking voice comes through, as it seldom did when he inhabited the Bugs character.

Avery's first take-away from Steinbeck was that a character with short-term memory is endlessly funny. Thus, he takes the license, as Joe Adamson comments in his seminal book Tex Avery: King of Cartoons, to do the same big gag sequence three times in a row--and make us laugh along with him. Part prank on the viewer and part comedic discovery, the structure of Fox and Hounds is a stroke of genius.

Avery never lost the knack for creating introductions that almost convince you he's serious. The introduction to this cartoon, with its breaking-dawn atmosphere, stylized landscapes and rotoscoped animation of the human form, deliberately sets up a decorum so it can be broken. One of Carl Stalling's pet pieces, a movement from The William Tell Overture, helps further this mood of no-kidding-folks.

This shot looks like something from a David O. Selznick production.

We now meet Willoughby, the "Lennie" hound, who belatedly realizes something's up, and that he'd better get in on the action.

Willoughby asks us (informally): "Which way did they go? Where did the dogs go?" Avery's interpretation of Lon Chaney Jr's Lennie lacks that actor's gravelly undertones (which would grow more pronounced and phlegmatic through the 1940s) but gets the staccato phrasing and the repetition just right.Willoughby has a remarkably odd run-cycle, which will get maximal use in this longer-than-average Warner Brothers cartoon.

This physics-defying run cycle. bolstered by a zany Stallings cue, sustains through a dissolve to another part of the woods. Much time has elapsed via that dissolve. After a few lopes, Willoughby informs us that he's a regular expert on these woods.

"I know every tree in this for-rest! Ev'ry single tree..."

The timing of Willoughby's collision with the tree could not be bettered.

Part of the gag with this character is his slow reaction time. He has to recover from the impact, look at the tree (for a long time) and finally deduce...

"There's one now!"

A look back at the tree, to reassure himself, is followed by a nod of "yep." Fade to black.

We know that this character's lack of wits will be the reason for this cartoon's existence. How his lack of wits will come into play is the question...

Snuffling out the trail, he comes across the fox.

Willoughby violates fox's personal space at length.

Fox makes his objection public record.

Oblivious to his lack of social grace, Willoughby introduces himself. Fox does same.

"My name's George."

Willoughby shakes George bodily and inquires if the fox has seen a fox anywhere.

The potential of this meeting dawns on George, who feigns innocence.

A rehash of the establishing Bugs and Elmer routine in the recent A Wild Hare is enhanced by Jack Webb-like cutting on new lines of dialogue. It's an old trick, but effective in punching up the ocean of difference in the two animals' mentality.Bugs inquires about a short cotton tail with Elmer; George displays his magnificent "long, bushy tail."

Avery really tucks into Willoughby's increasingly heated affirmatives.

"Oh, him..."

"He just passed here."

"Uh... which way did he go, George?"

George is wary of possible bodily harm as Willoughby shakes him and bounces with unrestrained joy. But he realizes there's fun to be had here...

"Well, I tell ya whatcha do..."

"Y'go down to dat ol' tree stump, an' turn right..."

"...until y'come to a rail fence."

"Yull find him right on de other side."

"Y'can't miss 'im!"

Willoughby is grateful for this intel, and shows his thanks with a big wet kiss.

He bounds away, stage left, so fast that it took several tries to get these screen grabs.

George does not wipe the kiss off his lips. He knows a greater reward awaits him.

Avery gets more use of that bizarre run cycle.

Cut to a new background that trucks down at leisure to show what happened.

Willoughby has been played for a fool. It takes him a few moments to deduce this.

The long look up, as if that will help matters, is priceless.

"Ya know..."

"That was the fox."

Willoughby's bulk is emphasized in his struggle to climb up the cliff. If there was an easier way to get back up here, he is not the dog to know it.

He remembers just enough to be ticked off.

George anticipates much sport and gaiety. As Willoughby lumbers his way, he dons a generic dog costume. The get-up's headpiece reveals Avery's hand as an artist, and strongly anticipates the character designs of his M-G-M cartoons released in 1946-1947.

And not a moment too soon. Willoughby's out for blood.

The gradual phase from rage to Willoughby's usual state of denseness is beautifully handled by the animator of this scene.

Willoughby hoists George as if he were an endtable. He speaks before his thoughts are formed, but remembers to introduce himself to this not-a-fox.

"My name's... uh..."

"Willoughby," the fox can't keep himself from saying.

Yeah-yeah! That's my name!

"My name's George."

(to audience) "Here we go again."

As if the previous sequence never happened, Willoughby shakes hands with George and re-asks if George has seen a little red fox. George goes through the same description--made funnier by the bagginess of his unconvincing dog suit--and a grateful Willoughby lumbers off again.

George pokes Willoughby's face for emphasis several times, in a demonstration of zero respect for his opponent. That doesn't prevent him from getting another full mouth kiss from the not-so-gentle giant.

Willoughby's next descent re-uses the animation (and, perhaps, the same footage) from the prior scene, so no need to recap it here. Willoughby's post-fall reaction is a sigh. Is it a "aw, crap, he fooled me again?" sigh, or a "why is life so hard all the time?" sigh? It's the opposite of what we expect from him, and it's a nice touch.

Another novel application of cartoon physics as the dog hoists himself up.

Willoughby is filled anew with determination, even if he doesn't know exactly why.

Still in false-dog mode, George enjoys a smoke as he awaits Willoughby's return.

"Say, George. He wasn't down there. I was down there once before, George..."

George discards his butt with a look of cool contempt on his costumed face.

In the gruff, resigned manner most recently seen in the character of Mike Ehrmantraut (as played by Jonathan Banks on Better Call Saul). George says, with condescension: "Ah, well..."

"Come on, Willoughby, Let's go get your fox."

All goes reasonably well 'til George is stuck in a hollow log.

The interior-log cutaway shots showcase some great Avery-based drawings as George struggles to get un-stuck and is shot from the log-projectile.

A fake dog/fox hybrid briefly appears.

Camera whips over to show Willoughby's utter astonishment.

Willoughby still hasn't gotten the sum of 2+2. Instead of dashing after the fox, as one does, he shakes the empty dog costume as he speaks to what he still believes is George. It takes a long time for the nickel to drop.

(to us) "Y'know, George was spoofin' us..."

"He was the fox all the time."

"But you just wait! I'll get 'im now..."

A brief foray into the cartoon chase.

Conflict source fills the frame; conflict-avoidant George leaps over it.

George and Willoughby use the bear's head as a launch. This engages a powerful antagonist.

For one moment, Willoughby succeeds at his goal. Almost.

Willoughby's skid-stops emphasize his mass, and his lack of control over same,

in a forceful and funny way.

A convenient animated rock--perfect!

Willoughby is right to feel proud. This may be the greatest accomplishment of his life to date.

He picks the wrong party to share in his delight. Here, Avery's performance has real fervor--he channels the childlike enthusiasm of Chaney's Lennie.

"I done a good thing!"

"I got the fox! I got the fox!"

"Come 'ere an' look..."

Reality of situation has now seeped into Willoughby's brain.

The timing of the dog's exit is beautiful--and so fast that little vapor wisps linger in the air, so the 1940 viewer wasn't too jarred by that high-speed vamoose.The bear's stunned reaction is a thing of beauty. Like Willoughby, he searches all around him, unable to yet feel anger at this bodily disturbance.

A-ha!

Falling leaves catch the camera's eye. It pans up to reveal Willoughby's current status.

The weight and ponderous movements of the bear are keenly felt through the work of this animator. We weren't expecting a moment of drama, but here it is.

Anatomy of a "take..."

My opponent can't die! We've still got two and a half

minutes left on this thing! What'll I do?

Routine 22-C: Ye Olde Hot-Foot.

This sequence bogs down the pace of what has been, by anyone's standards, a leisurely and non-hurried affair. In this shot, the glacial timing of the fox's business with the matches, though beautifully animated, takes ages to achieve what Avery would take three seconds to do by 1945. This timing seems deliberate to further exasperate the viewer.

Great sneak cycle of the fox--it has a lot of "sock" in the thrusting, expressive movement.

Avery's fourth wall is a moot point by this time, and George casually reminds

us not to laugh while he does his stuff.

The next shot has a logic flaw--rare in Avery's spartan storylines. The static background painting of the un-moving bear's leg, as George takes an aeon to set up the hot-foot, draws attention to itself. A small moving cycle showing some life in the bear's body could have been used here, as in the prior scene. The animal's weight would plant him firmly on the ground and still allow for the gag. It puts a weird damper on the proceedings for a few seconds.

I wish this cartoon had been restored, back when WHV cared about their history. Thank heavens it isn't in the public domain, but all prints of it are dark and muzzy. That much of the settings are already dark and muzzy doesn't help matters.

In another (minor) echo of A Wild Hare, George hides behind a tree to watch the results.

Tension builds, despite the sudden sluggishness that's seized this cartoon.

A clever visualization of the bear's nervous system and pain receptors, leading up to his brain, brings home the effect of the hot-foot.

Bear leaps out of camera range...

...then hits the road with some gorgeous airbrushed and drybrushed FX animation.

Threat to well-being removed. Here is where the typical Hollywood cartoon would wrap things up. Predator and prey find common ground, perhaps shake paws, with prey giving predator a quick razz just to remind him who's boss.

But we are 99 seconds from the end--an eternity for an animated film--and there is a final assault on the audience's patience yet to come.

We almost get that ending: Willoughby clambers down from three, shakes George's hand, and assures him:

"I wasn't a bit a-scared o' that bear, George..."

"Not a bit a-scared--" (falls in dead faint)

George shows genuine concern as we get one of those lovely triple-exposure cross-dissolves...

Avery does an abridged recap of the opening sequence.

There's a beautiful twist here. It would have been easy (and tempting) for Avery to do an utter repetition of what's happened twice in this cartoon. Willoughby leaps out of his kennel...

...takes a look around (in a pose that looks like a post-war drawing--almost Art Davis-y)......and coaxes George out of the kennel, where he's apparently been staying for awhile. All emnity forgotten in Willoughby's head. George is a friend. For Avery, this is sentimental stuff.

"Come on out, George!"

"They've done gone to get the fox, George!"

"Which way did they go, George?"

George recovers from Willoughby's rough handling, and damned if he doesn't give out the same directions, accented with the same hand gestures...

There is no need to recap the dialogue here.

A few nose-pokes re-establishes George's lack of respect for Willoughby.

Willoughby again gives with the lip-kiss:

...and he's off!

Repeated animation, backgrounds, music... at this point, one has to laugh. The comic inevitability weighs a ton.A long silence is barely punctuated by a ping. The camera trucks down the cliff, much faster this time, to reveal the lack of crash and burn SFX...

I'd love to know how those mattresses got there. Perhaps a lot of time elapsed when "came another day."

"Huh-huh. Ya know... I ain't so dumb!"

Willoughby relaxes as the iris closes in.

Ugly reissue closing credits.

Of Fox and Hounds was re-issued twice in WB's Blue Ribbon program--the last time in February 1954, where it rubbed shoulders with a late Avery M-G-M masterwork, Drag-a-Long Droopy. By this time, ihe feel of Hollywood animation had shifted mightily from the Disney-based, dimensionally contoured look of this cartoon. Lower budgets stifled the flowing animation that reached its zenith in the mid-'40s. The influence of modern design affected Avery's work. In interviews, Avery said that he welcomed the change, particularly in the backgrounds, which looked like a manicured golf course with their inescapable motif of green, brown and blue.

It was more affordable to do the UPA bit--less detail to the backgrounds, less intricate movement needed for the animation. That, more than aesthetic taste, was what drove animation studios like Famous and Walter Lantz to shed the old-school storybook look, whether they understood how to use modern graphic elements or not. Warner Brothers was an early adapter to the new look, and the Chuck Jones and Friz Freleng units became comfortable with these settings and made them work in the service of broad, character-based comedy.

This 14 year-old cartoon might have seemed old hat, especially to hip young viewers who'd latched onto the UPA style, and dug what Chuck Jones and Maurice Noble were doing in the current Warners cartoons. The humor of this film, with its built-in endurance trial for the viewer, was still effective. Avery still found value in the beauty of repetition. Late M-G-M cartoons like Magical Maestro, The Three Little Pups, Billy Boy and a series of Droopy cartoons that pit him against the arrogant bulldog Spike, in a string of spot-gag blackouts, make sublime use of the familiarity of their gags and their litany.

The dark comedy of Fox and Hounds feels timely today, as so many of us have elderly relatives and friends who struggle with dementia and memory loss. The greatest comedians dig deep into life's little ups and downs. To laugh at Willoughby for going through a physically trying and traumatic ordeal three times might be theraputic for those who deal with a beloved aunt who still knows who you are, but can't remember what she did 10 minutes ago.

The thought that you or I might someday lose our ability to recall things is horrific. Such fears are ideal fodder for comedy. We laugh at our worst worries, via an exaggeration of them, and the blow of reality is softened. Whether Avery and his gag-men had this notion in mind (which is a probable 'no'), they, with the artistry and skill of their animators, put a worrisome facet of the human condition into comedic relief--and sustained a simple idea for 10 minutes. That an animated cartoon--dismissed as kid stuff by many--could hold a mirror up to a fear of mankind, and bring laughter to us instead of more terror, is a powerful thing.

PS: A thank-you to everyone who has left comments over the past few months. For some reason, Blogger no longer sends me notifications when new comments are left. I approved over a dozen comments on 8/14/18. Apologies if you've been wondering why I hadn't okayed your feedback, which I greatly value. I'll pay closer attention to the comments section from now on.

I didn't name any animators in this post, but if anyone wishes to detail who did what, please leave a comment below. I have a familiarity with many animators' styles, but don't want to hazard a wrong guess.

_____________

Next: Back to black and white, in one of my least favorite Avery cartoons, The Haunted Mouse--one of two Avery cartoons issued on February 15, 1941.

I think this Charles Addams cartoon could easily be captioned: "Tex Avery sees Of Mice and Men." (Or, "Donald Trump sees 12 Years a Slave.")

ReplyDeleteIf you wanted proof of what a watershed moment "A Wild Hare" really is, this and "Crackpot Quail" are it. Especially here, when Bob Givens' design of the fox is essentially his Bugs, the voice is more or less the same, and a lot of the routines would become Bugs staples. It's still a charming, great cartoon thanks mainly to Willoughby, but the fox is a nothing. Whereas in "A Wild Hare", both Bugs and Elmer are interesting well-acted characters. He didn't really recreate that two-character dynamic well again until Spike and Droopy, which got most of the laffs from the energy and contrasts. I guess it's the difference between "great" and "really great."

Friz Freleng loved this cartoon so much he basically remade it with Bugs some ten years later as the also excellent "Foxy By Proxy". It actually reuses that opening morning footage verbatim (with a new soundtrack). Freberg reprises the Lennie voice in that one to hilarious effect. ("I done a good thing! All by myself I caught a train!")

Personal note: years ago I actually returned a print of "Fox and Hounds", because it was not as advertised. I thought I was getting a Kodachrome print (wherein the possibility of the original title card was in my favor), but instead got an Anscochrome print (late '50s TV reissue). It was still a nice print and I now regret it, but daddy needed rent money.

I forgot about "Foxy By Proxy." Thanks, as ever, for your astute and entertaining comments!

ReplyDeleteAlso, "The Abominable Snow Bunny", which is perhaps the most familiar "Lennie" spoof on the popular network Bugs Bunny shows. That was where I first took not of the whole "George" theme, and then when I later saw Hoppy Go Lucky (where "Bennie" from Cat Tails for Two returned, with Sylvester as George, up against Hippety Hopper), I wondered what this was being taken from, until I finally read Of Mice and Men in high school. Then, it was "So THAT's where they got that!"

ReplyDeleteChuck Jones also apparently loved the 'four feet up at once" climbing gag, because he'd re-use it for his super-cute squirrel a dozen years later in "Much Ado About Nutting".

ReplyDeleteOutside of the closing to "Little Tinker" at MGM, this is probably the sweetest ending ever to an Avery cartoon, and that plays into the dynamic that differentiates Bugs in "A Wild Hare" from the similar-sounding fox here. In the former, Tex made it so the audience's sympathies are with the rabbit in his battle with the dumber Elmer; in "Of Fox and Hounds" and "The Crackpot Quail" that followed, Avery makes sure the audience's sympathies are always with the dog over their smart-aleck opponents (which in itself goes on to motivate the controversial ending of Avery's "The Heckling Hare". Leon and/or J.L. may not have liked the way the cartoon ended, but Avery ended in a way where neither Bugs nor Willoughby emerge triumphant, but end as co-equal plummeters off another cliff).

This short was released as a part of French Tex Avery MGM shorts on DVD, as a 1995 print, which in my opinion looks much better than Laserdisc print from The Golden Age of Looney Tunes release.

ReplyDeleteLooks like Johnny Johnsen flawlessly recreated the opening background pan at MGM for OUT-FOXED (1949).

ReplyDelete