DVD-Blu-Ray Availability: Looney Tunes Platinum Collection: Volume 2 (available in both formats)

You may view the complete version of this cartoon HERE.

<><><><><><><><><><>

PREFACE: This will be the longest, most involved chapter in this blog. It marks the fifth year of this quixotic ode to one of my favorite filmmakers.

When I started this blog in 2013, I assumed I'd breeze through Tex Avery's Warner Brothers cartoons in a year or two. Life had different plans for me. With luck, I'll reach the end here by 2023, assuming the free Internet, blogs and computers still exist, and we're not talking into sentient sticks and beaming our thoughts into some shared cephalopodic mind-screen.

I have been mesmerized by animation since infancy. The first motion picture I saw was a revival of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in Tallahassee, Florida in 1965. My grandmother later delighted in recalling my sheer terror at moments in the film, but I wasn't traumatized--just fascinated and compelled to see more, at a point when I might not have been able to discern live-action footage from hand-drawn animation.

Television had loads of limited-animation programming, but, as I discovered, early in the morning, local stations showed older cartoons. They looked, sounded and felt different. Like Snow White, they convinced me more of real-life movement than the mechanical walk cycles of The Flintstones, or the illustrated radio of Rocky and Bullwinkle.

The cartoons that interested me most came from a large package of Warner Brothers shorts purchased by Associated Artists Productions. This image, and not the iconic Warner Brothers rings, opened the cartoons I saw on early morning and afternoon TV broadcasts:

It became easier to connect the dots: William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, producers of so much TV dreck, did those beautifully-animated Tom and Jerry shorts of the 1940s! Animators who worked for Disney also worked for M-G-M, Lantz and Warner Brothers!

It became easier to connect the dots: William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, producers of so much TV dreck, did those beautifully-animated Tom and Jerry shorts of the 1940s! Animators who worked for Disney also worked for M-G-M, Lantz and Warner Brothers!

One early godsend was the January-February 1975 issue of Film Comment with a large section on classic Hollywood cartoons--a suite of articles that coalesced with the critical thinking I'd begun about these films. The discovery of this issue, in 1979, gave me a sense of purpose in my interest in animation. These were films worth thinking about and studying. They weren't expressly made for children. They had value as containers of American popular culture and history.

Books like Joe Adamson's Tex Avery: King of Cartoons and Leonard Maltin's Of Mice and Magic arrived around this time. (I confess that I flim-flammed Adamson's book from the library of a casual friend; once I had it, I simply couldn't give it back.) By this time, I'd discovered and fallen in love with earlier animation--the pre-1934 output of the Max Fleischer studios. Those eerie, inscrutable cartoons remain, with the work of Tex Avery, my favorites of all animated films. They, along with other East and West Coast pre-Code animation, paved the way for the "anything is possible" credo that helped give Tex Avery's work such high and lasting value.

I'd seen earlier cartoons with the same basic set-up (1939's Hare-um Scare-um, 1940's Elmer's Candid Camera). They were the obvious forefathers of A Wild Hare, as confirmed by Joe Adamson's book. And while I have an affection for the Chuck Jones proto-Bugs and Elmer of the latter film, A Wild Hare impressed me with the gauntlet it threw down. Jones' cartoon is charming but harmless; Avery's issued a mission statement that still reverberated 40 years hence in the ramshackle walls of Moore Auditorium at FSU.

I'd seen earlier cartoons with the same basic set-up (1939's Hare-um Scare-um, 1940's Elmer's Candid Camera). They were the obvious forefathers of A Wild Hare, as confirmed by Joe Adamson's book. And while I have an affection for the Chuck Jones proto-Bugs and Elmer of the latter film, A Wild Hare impressed me with the gauntlet it threw down. Jones' cartoon is charming but harmless; Avery's issued a mission statement that still reverberated 40 years hence in the ramshackle walls of Moore Auditorium at FSU.

We know what's next, of course. It's possible that 1940 audiences had some inkling that this mail-order huntsman was not destined to walk home with his game-bag filled. The all-important how and why would confound their expectations in a significant, game-changing way.

Fudd stoops over and squints, as if to ascertain that this burrow in the ground is what the magazine article described.

Stalling adds a charming "The Fountain in the Park," a c. 1880 pop song that every child of the 20th century knew by heart.

Bugs, yet un-named, would go through several subtle makeovers in looks and personality, but he arrives more or less fully formed. Only a touch of the hayseed remains in his DNA. The defining Bugs attitude--the cool demeanor, the false enthusiasm, the seeming cordiality to his ofay foes--is here. He is not a dribbling goof, a demented yokel or an unhinged sociopath. He is a likable, engaging anti-hero who transcends mere heroism.

With a pause for carrot consumption, and a more relaxed posture, Mel Blanc, as Bugs, first utters those immortal words...

As this animator's scene ends, indulge me in a brief sidebar about the performance of Arthur Q. Bryan. As taken-for-granted as Mel Blanc is revered, Bryan brought a warmth and expression to the Fudd role that makes him as rounded and tangible as Bugs or Daffy. Fudd is a fool: the white man to end them all, his ignorance exceeds his self-understanding. He is destined to be the fall guy, but he never gets out of bed feeling doubt. He is a most likable buffoon, and we feel for him as we don't most other "villain" antagonists in classic animation. You want to pat him on the shoulder and say "there, there, old fellow."

As this animator's scene ends, indulge me in a brief sidebar about the performance of Arthur Q. Bryan. As taken-for-granted as Mel Blanc is revered, Bryan brought a warmth and expression to the Fudd role that makes him as rounded and tangible as Bugs or Daffy. Fudd is a fool: the white man to end them all, his ignorance exceeds his self-understanding. He is destined to be the fall guy, but he never gets out of bed feeling doubt. He is a most likable buffoon, and we feel for him as we don't most other "villain" antagonists in classic animation. You want to pat him on the shoulder and say "there, there, old fellow."

Bugs relaxes. He has sized up this homo sapien and found him to be wanting in the balance. What might have been a routine day of napping, foraging and avoiding natural predators has suddenly turned into a fun fest. The rabbit will enjoy himself immensely.

This scene contains four names of Hollywood actresses--all carefully chosen to exploit Fudd's vocal quirks. One of them was cut from the cartoon for its 1944 reissue, since the femme in question, the great comedienne Carole Lombard, had died in a fairly recent plane crash.

New animator. Elmer's attempts to wipe away this comedic/sexual violation is perfectly scored by Stalling with a dithering violin figure. It makes an otherwise small gesture larger and therefore funnier.

The CARROTS sign has neon piping, which Stallings accentuates with some modernistic stings. Fudd whistles and calls for the rabbit as if he were a simpering hound.

Rabbit nods as Fudd gloats. It takes even longer for the nickel to drop this time...

Fudd receives a third kiss (this time on his little pink nose) as reality slows creeps into his consciousness...

"Uh oh," Bryan croaks as Fudd, sounding like a distressed spring mattress. He slowly turns to see what he has in his hand...

"Confidentially... well... you know," skunk (voiced by Blanc) says, with a knowing elbow nudge to the hunter's jowls. This appears to be another animator.

As Fudd lowers the skunk's fluffy tail, a squeak like an unoiled barn door accompanies it. Because that's funny.

"Y'got me, pal... y'got me." Fudd's delight turns to chagrin as the rabbit's contortions seem real.

Robert McKimson's finest moment as an animator begins here. In concert with Mel Blanc's performance as the mock-dying rabbit, McKimson's work brings a gravity to the situation that creates nervous tension in the viewer. This is a joke, right? The little gray rabbit's not really dying, is he?

The tenderness in Fudd's eyes, and the concern on his face, often shown in a diabolically difficult downward-facing perspective, is masterful work in its own right. That it so effectively blurs the line between comedy and tragedy is powerful stuff. Like the Cab Calloway song sequences in the Fleischer cartoons Snow White (1933) and Minnie the Moocher ('32), this animation takes us, for a handful of seconds, to another place beyond farce, beyond Disney, beyond the limitations of the Hollywood cartoon.

Avery still had far to go to perfect his comedic/filmic vision. Perhaps he never reached the ideal he had in his head. But the quantum leap from Porky's Duck Hunt--the 1937 birth of this notion--to the beautiful playbook of A Wild Hare is a great feat. That earlier cartoon remains one of it's maker's true classics, but the honed-down focus of this film makes it a major milestone in the development of the art form of animation. It's a magic moment that could only happen once. Never did a movie-maker so have the element of surprise in his favor, and so aptly use it to such great effect.

Avery still had far to go to perfect his comedic/filmic vision. Perhaps he never reached the ideal he had in his head. But the quantum leap from Porky's Duck Hunt--the 1937 birth of this notion--to the beautiful playbook of A Wild Hare is a great feat. That earlier cartoon remains one of it's maker's true classics, but the honed-down focus of this film makes it a major milestone in the development of the art form of animation. It's a magic moment that could only happen once. Never did a movie-maker so have the element of surprise in his favor, and so aptly use it to such great effect.

When I started this blog in 2013, I assumed I'd breeze through Tex Avery's Warner Brothers cartoons in a year or two. Life had different plans for me. With luck, I'll reach the end here by 2023, assuming the free Internet, blogs and computers still exist, and we're not talking into sentient sticks and beaming our thoughts into some shared cephalopodic mind-screen.

I have been mesmerized by animation since infancy. The first motion picture I saw was a revival of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in Tallahassee, Florida in 1965. My grandmother later delighted in recalling my sheer terror at moments in the film, but I wasn't traumatized--just fascinated and compelled to see more, at a point when I might not have been able to discern live-action footage from hand-drawn animation.

Television had loads of limited-animation programming, but, as I discovered, early in the morning, local stations showed older cartoons. They looked, sounded and felt different. Like Snow White, they convinced me more of real-life movement than the mechanical walk cycles of The Flintstones, or the illustrated radio of Rocky and Bullwinkle.

The cartoons that interested me most came from a large package of Warner Brothers shorts purchased by Associated Artists Productions. This image, and not the iconic Warner Brothers rings, opened the cartoons I saw on early morning and afternoon TV broadcasts:

My family didn't get a color TV until 1976, so my earliest views of these, and the classic M-G-M cartoon library, plus Famous Studios, Terrytoons, Walter Lantz and the odd Disney short, were in grainy, low-rez black and white.

As a child, I had no clear idea how old these cartoons were. I knew they preceded my birth, and that the Hanna-Barbera TV cartoons--plus the other contemporary ventures into limited animation that dominated broadcast time--were more recent. No reference books existed, and there was no way to summon up a cartoon at a moment's notice.

Local TV stations randomly ran their 16 millimeter prints of these films, three to four in a half-hour time slot. Cartoon endings were regularly cut off if the show went into overtime (i.e., exceeded the time alloted to ads). More than once, film broke during a live broadcast. Said cartoon would often next be seen missing a hunk of footage, causing an interruption like a skip on a vinyl record.

These cartoons were time-fillers to pad out afternoon and wee-hour programming, sell advertising space to (usually) local merchants and give children something to stare at, and thus keep out of trouble/their parents' lives.

Few people, aside from kids, cared about these broadcasts. The television stations cared about the ads that they packed in-between these shorts. A passing adult might chuckle in remembrance of seeing such cartoon fare in their childhood. And there must have been older animation enthusiasts who had some inkling of knowledge of the art form's history, and who watched these crummy broadcasts as a means to see these elusive films.

That's what I became in my latter years of high school. The golden hours of 3 to 5 PM offered a chance to see x number of cartoons daily--at this time, a mix of Warners, M-G-M and Walter Lantz material, programmed with no rhyme or reason. By then. I'd gleaned first insights behind how these remarkable films came to be--mostly misinformation, but at this time (circa 1978) any info was welcome (if later refuted by proven fact).

It became easier to connect the dots: William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, producers of so much TV dreck, did those beautifully-animated Tom and Jerry shorts of the 1940s! Animators who worked for Disney also worked for M-G-M, Lantz and Warner Brothers!

It became easier to connect the dots: William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, producers of so much TV dreck, did those beautifully-animated Tom and Jerry shorts of the 1940s! Animators who worked for Disney also worked for M-G-M, Lantz and Warner Brothers! One early godsend was the January-February 1975 issue of Film Comment with a large section on classic Hollywood cartoons--a suite of articles that coalesced with the critical thinking I'd begun about these films. The discovery of this issue, in 1979, gave me a sense of purpose in my interest in animation. These were films worth thinking about and studying. They weren't expressly made for children. They had value as containers of American popular culture and history.

Books like Joe Adamson's Tex Avery: King of Cartoons and Leonard Maltin's Of Mice and Magic arrived around this time. (I confess that I flim-flammed Adamson's book from the library of a casual friend; once I had it, I simply couldn't give it back.) By this time, I'd discovered and fallen in love with earlier animation--the pre-1934 output of the Max Fleischer studios. Those eerie, inscrutable cartoons remain, with the work of Tex Avery, my favorites of all animated films. They, along with other East and West Coast pre-Code animation, paved the way for the "anything is possible" credo that helped give Tex Avery's work such high and lasting value.

In college, my first job was as 16 millimeter projectionist for Florida State University's film program. Its director, Michael Ogden, was a good friend of mine, and he shared my interest in classic cartoons. At age 17-18, I programmed a few nights of classic animation, including an all-Avery show which featured the re-issue version of the cartoon we're eventually going to discuss here today.

The prints were salmon-pink, battered, badly spliced and scratched to hell and back, but they still had the power to make an audience laugh. And this was the title-card to today's cartoon under examination, as seen by the collegiate audience:

I'd seen earlier cartoons with the same basic set-up (1939's Hare-um Scare-um, 1940's Elmer's Candid Camera). They were the obvious forefathers of A Wild Hare, as confirmed by Joe Adamson's book. And while I have an affection for the Chuck Jones proto-Bugs and Elmer of the latter film, A Wild Hare impressed me with the gauntlet it threw down. Jones' cartoon is charming but harmless; Avery's issued a mission statement that still reverberated 40 years hence in the ramshackle walls of Moore Auditorium at FSU.

I'd seen earlier cartoons with the same basic set-up (1939's Hare-um Scare-um, 1940's Elmer's Candid Camera). They were the obvious forefathers of A Wild Hare, as confirmed by Joe Adamson's book. And while I have an affection for the Chuck Jones proto-Bugs and Elmer of the latter film, A Wild Hare impressed me with the gauntlet it threw down. Jones' cartoon is charming but harmless; Avery's issued a mission statement that still reverberated 40 years hence in the ramshackle walls of Moore Auditorium at FSU.

40-ish years after that screening, the cartoon I knew as The Wild Hare still impresses me with its economy, sophistication and the skill of its humor and movie-making. I can summon a lovely restored copy of the uncut original version any old time I like. I can pause it--a feat not possible with the 16 millimeter copies of classic cartoons I acquired in the 1980s, except on a Moviola--and I can study it to my heart's content. But it never becomes stale.

Avery would go on to refine its basic tenets--and surpass its delivery in terms of timing, efficiency and attack--but A Wild Hare remains one of the key films in his career. Its influence was viral the moment it hit American theater screens, and it brought the animated cartoon out of the 1930s and into the harder edges of the next decade.

Avery had more or less created this cartoon's format three years earlier with his black and white Porky's Duck Hunt. The significant differences in how he handles the same template, from 1937 to 1940, is what's vital here. Duck Hunt is florid, brassy and attention-getting in its showboating screwball comedy. It whistles, winks and otherwise hot-foots its audience with the nuttiness of its goings-on. It's no less great a cartoon for this grand-standing and, perhaps, it had to expend the extra effort to get its new kind of screwball character across to 1937 audiences.

A Wild Hare is played cool, dry and subtle. It's the work of a skilled movie-maker, wisened by the ups and downs of his past efforts. And if its rabbit star isn't 100% the Bugs Bunny we know and love, he's very close. The attitude is there--in need of small refinements, which Avery, Friz Freleng and Chuck Jones would provide in coming films.

By the time it was in production, the Leon Schlesinger cartoon studio's key players were in place--a strong slate of voice talent; Carl Stallings' intricate, perceptive and supportive musical scores; most of the studio's great animators and artists and all of its truly important and influential directors. (Frank Tashlin, perhaps the most cinematically gifted cartoon director, was away from Schlesinger's but would return after Avery's 1941 departure.)

These creators still felt growing pains. Much of the 1939/1940 cartoon season is tough going, and, in hindsight, the sluggishness and mis-steps seem awkward. But in their time, the Warners cartoons broke new ground in a direction that defied the influence of Walt Disney, with his studio's increased tendency towards "realism" and "natural movement"--anathema to the vitality, humor and raw promise of the Hollywood theatrical cartoon.

A Wild Hare did not signal an immediate switch in tone, treatment and quality. Its influences rippled throughout the industry, but not until 1943 or so do we see a widespread and significant improvement in the content, pacing and expression that would soon seem second-nature to the art form. It came out of a time of struggle, and is a moment of divine coalescence. Avery would, arguably, not make another film this good for the remainder of his time at Schlesinger's studio. (There are a few that come very close.)

We iris on on a situation that even casual cartoon viewers know by heart:

Avery would soon abandon the bramble of multiplane clutter that fills this shot. The limbs and foliage serve as immediate shorthand: we're in the woods. The stage is set for one of the most intimate animated cartoons. Its actions take place within a reasonable radius of 20 feet; it involves two characters (with a minor role by a skunk and one cutaway to birds in a tree, late in the film). Like the starvation gags that pepper Avery's films--a lone bean on a large white plate--the substance of A Wild Hare is barren of the gags, distractions and jostles that have characterized the director's work until now.

Elmer Fudd, who existed in name as an alias for Egghead in 1938's A Feud There Was, and was further refined by Chuck Jones for Elmer's Candid Camera, is fully realized here. Fudd, the ultimate caricature of a clueless, entitled Caucasian. Bald Fudd is an adult child. He knows he wants something, but has no clue why he needs it. Meek and submissive at times, he's also harsh and vindictive. The vital thing he lacks is intelligence--either book-larnin' or animal/instinct "common sense."

One imagines him slowly reading a magazine article on rabbit hunting and, after much deliberation, heading to a sporting goods store, purchasing a hunting outfit and a rifle and heading to the woods, with no more education or information than a whim. And that's where this story begins.

We all know the words:

"Shhh..."

"Be vewwy, vewwy quiet..."

"I'm hunting wabbits!"

(moment of suppwise)

"Wabbit twacks!"

We know what's next, of course. It's possible that 1940 audiences had some inkling that this mail-order huntsman was not destined to walk home with his game-bag filled. The all-important how and why would confound their expectations in a significant, game-changing way.

Fudd stoops over and squints, as if to ascertain that this burrow in the ground is what the magazine article described.

It is, indeed:

"A wabbit hole!"

(Fudd chortles inanely)

"Wabbits wuv cawwots!"

(composite of action; camera trucks left)

Devon Baxter and Thad Komorowski have kindly offered their identifications of the animation crew that drew A Wild Hare. Mark Kausler, the veteran animator and tireless champion of these classic cartoons, read over their IDs. He confirmed most of them, and wasn't sure about a few. Those'll be noted accordingly.

Virgil Ross appears to be the animator for this opening scene. The cut to Fudd's close-up may be another animator.

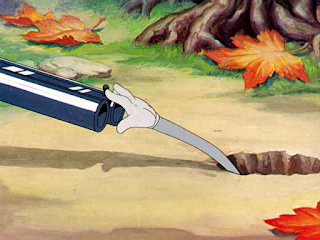

We switch to Robert McKimson, the most technically gifted animator on Leon Schlesinger's payroll. He makes a thing of beauty out of a pantomime scene that most other cartoons would have reduced to a mere hand grab. Here, Avery, McKimson and musical director Carl Stalling collaborate on elegant and subtle physical comedy:

What occurs in this brief scene is not charming, as it might play in a Disney short. It's funny. The idea of the yet-unseen rabbit's hand becoming a three-legged entity, with a sense of suspicion, alertness and investigation, is worthy of a Buster Keaton or Jacques Tati. It seems simple, but every gesture, action and reaction is played with assurance.

Another, less sure hand documents Fudd's reaction and approach from behind the tree:

McKimson returns to continue the artistry of the hand-as-sentient-being pantomime.

The hand thunks the gun barrel three times to ascertain that it's metal.

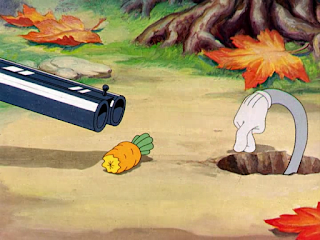

Root vegetable is returned half-eaten.

It's too good to surrender...

At this moment, the game realizes it can play with the hunter--and not in the pre-established zany, aggressive manner of a Daffy Duck. Here, the table is subtly turned, and the yet-unshown rabbit realizes that he is in no way powerless.Stalling adds a charming "The Fountain in the Park," a c. 1880 pop song that every child of the 20th century knew by heart.

A wiser Fudd would have given up and headed home after this--but that he doesn't is a great and lasting gift to film comedy.

Animation changes to what Devon Baxter feels is Paul Smith--the Walter Lantz animator/director who drove that studio's cartoons into grinding misery in the 1960s. This animator, while lacking the grace of a Rod Scribner or Virgil Ross, has a spiky, misshapen style that's appealing on its own merits, but awkward in the context of the others' work. His was the honor of drawing the first scenes of Bugs Bunny here.

But first: the good ol' tie-the-shotgun-barrels-in-a-bow bit. Enhanced by the animator's weird drawings and Stallings' trombone arrangement, it's as funny as it ever got...

Animation changes to what Devon Baxter feels is Paul Smith--the Walter Lantz animator/director who drove that studio's cartoons into grinding misery in the 1960s. This animator, while lacking the grace of a Rod Scribner or Virgil Ross, has a spiky, misshapen style that's appealing on its own merits, but awkward in the context of the others' work. His was the honor of drawing the first scenes of Bugs Bunny here.

But first: the good ol' tie-the-shotgun-barrels-in-a-bow bit. Enhanced by the animator's weird drawings and Stallings' trombone arrangement, it's as funny as it ever got...

Poor Fudd is bitch-slapped by this Gordian knot, and reacts in anger:

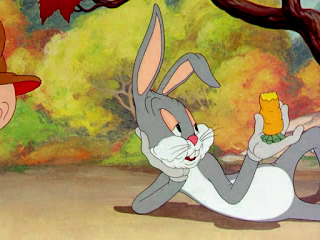

Elmer digs, and the camera pans right to debut the greatest entity that ever graced the animated screen. He utters a now-immortal entrance line, derived from Avery's high school days, where it was used as a Texas equivalent to "greetings, gate."

Bugs, yet un-named, would go through several subtle makeovers in looks and personality, but he arrives more or less fully formed. Only a touch of the hayseed remains in his DNA. The defining Bugs attitude--the cool demeanor, the false enthusiasm, the seeming cordiality to his ofay foes--is here. He is not a dribbling goof, a demented yokel or an unhinged sociopath. He is a likable, engaging anti-hero who transcends mere heroism.

With a pause for carrot consumption, and a more relaxed posture, Mel Blanc, as Bugs, first utters those immortal words...

Ehhh...

What's up, Doc?

"There's a wabbit down here. An' I'm twyin' ta catch him!"

As this animator's scene ends, indulge me in a brief sidebar about the performance of Arthur Q. Bryan. As taken-for-granted as Mel Blanc is revered, Bryan brought a warmth and expression to the Fudd role that makes him as rounded and tangible as Bugs or Daffy. Fudd is a fool: the white man to end them all, his ignorance exceeds his self-understanding. He is destined to be the fall guy, but he never gets out of bed feeling doubt. He is a most likable buffoon, and we feel for him as we don't most other "villain" antagonists in classic animation. You want to pat him on the shoulder and say "there, there, old fellow."

As this animator's scene ends, indulge me in a brief sidebar about the performance of Arthur Q. Bryan. As taken-for-granted as Mel Blanc is revered, Bryan brought a warmth and expression to the Fudd role that makes him as rounded and tangible as Bugs or Daffy. Fudd is a fool: the white man to end them all, his ignorance exceeds his self-understanding. He is destined to be the fall guy, but he never gets out of bed feeling doubt. He is a most likable buffoon, and we feel for him as we don't most other "villain" antagonists in classic animation. You want to pat him on the shoulder and say "there, there, old fellow."Bugs relaxes. He has sized up this homo sapien and found him to be wanting in the balance. What might have been a routine day of napping, foraging and avoiding natural predators has suddenly turned into a fun fest. The rabbit will enjoy himself immensely.

We are now back to Virgil Ross, whose drawings in this tight medium shot fully show the rabbit's (a) skepticism (b) poker-faced amusement (c) silent meditations on the things he's going to do to this oblivious honky.

I'm sure this attitude was present in Avery's head, and evident on the storyboards, but it's so imbued in Ross' animation that the illusion of life--that suspension of disbelief that Avery so enjoyed lampooning--cloaks the viewer. We aren't watching a distanced cartoon figure. We're watching a friend--or someone we wish we could know.

Rabbit takes bait: "Ehhh... whaddaya mean, 'wabbit'?"

To his surprise, Fudd, so caught up in his goal, fails to see him as the prey, and engages him in a dialogue.

We switch animators to Rod Scribner, who is beloved for his unhinged work in Bob Clampett's 1940s cartoons. Scribner, like Emery Hawkins, had eccentric tendencies in his work, but could play it straight. In Avery's unit, he was a solid and expressive animator.

In a refinement and expansion of a routine in Elmer's Candid Camera, Fudd describes Bugs to himself, still not hep to the jive by any means. The animation poses tell the story, and spare me replicating the joyous voice-work of Bryan and Blanc:

It takes awhile for the nickel to drop, to quote Raymond Chandler, but Fudd gets the picture, and confides in us: (animator ID uncertain for this brief scene)

"I think this fellow is an ar-aye-bee-bee-eye-tee."

Virgil Ross takes over for the moment when prey informs predator that he is what he is.

The rabbit has a tougher Brooklyn accent than he would have in his glory days. At this point in animation history, giving a woodland creature a street-tough demeanor and patois was enough to buck convention.

The rabbit's glance over his shoulder, as if to allay conspirators, is priceless.

"Confidentially..."

" I AM A WABBIT!!!"

As tinnitus overwhelms Fudd, rabbit indulges in screwball body-language for his exit.

"Ehh... last look!"

Fudd is not easily discouraged.

We switch animators here. The transitions from artist to artist are unpredictable in the Schlesinger cartoons. Their directors tried to play to each animator's strengths and specialties, while assigning each man enough work to keep him gainfully occupied. The slight changes in the characters--which is inevitable in hand-drawn animation--probably didn't dawn on contemporary audiences. They may indeed become more noticeable in the decades ahead, as neural logic, and not the human eye and hand, guide the future of animation. No one can figure out who this next animator is...This scene contains four names of Hollywood actresses--all carefully chosen to exploit Fudd's vocal quirks. One of them was cut from the cartoon for its 1944 reissue, since the femme in question, the great comedienne Carole Lombard, had died in a fairly recent plane crash.

To the rabbit's "Guess who?" Fudd answers:

"Hedy Wamaww?... Cahwol Wombard?... Wosemawwy Wane?"

Rabbit nopes 'em all.

"Owivvia de Haviwend." Wong again.

A dim light dawns. "Say... you wouldn't be that scwewy wabbit, wouldja?"

Rabbit responds with a tag familiar from radio: "Hmmm..."

"Could be!"

Rabbit then plants a big, sloppy kiss on Fudd's lips: Elmer's first #metoo moment, and a humiliating device that the rabbit will employ later herein and in subsequent early cartoons. Devon Baxter notes that this device was used by Charlie Chaplin in his 1916 Mutual short film The Floor Walker. In this rabbit's hands, it becomes something new all over again.

The rabbit is forgiven his Bugs Hardaway-worthy spinning goof move.

In this moment, Avery reveals that he still has ground to break on his timing--which is tremedously fast for a cartoon that was created in 1939, but still far from the utter obsessive refinement it'll undergo during his stay at M-G-M. This leisurely dive into the rabbit hole, graced with nice animation, lasts four times longer than a similar scene in a c. 1946 Avery cartoon.

Humiliated and frustrated, Fudd corners the prey-that-is-not-prey, as we again switch animators to Robert McKimson:

The worst he can call his foe is "you mean ol' wabbit.."

and he gets a second kiss for his trouble.

Rabbit's fey look is the first inkling of an aspect of Bugs Bunny that defines the character and is part of his appeal. He's sexually ambiguous and socially aloof. Bugs' main goal is a peaceful life. He'd rather not be bothered with the slings and awwows, er, arrows of the civilized world. A stack of carrots, a good book and a bit of leisure suits him best. But he will defend his right to the quiet life with every ounce of his wits and skill. This sometimes includes crossing societal lines, the better to disorient and shock his antagonists. Kissing, like cross-dressing (of which the '40s Bugs will become a master), is a daring way to disarm hostility. It cuts to the core of masculinity issues, and in some cases, that might be enough to make a hostile party wave the white flag and go home.New animator. Elmer's attempts to wipe away this comedic/sexual violation is perfectly scored by Stalling with a dithering violin figure. It makes an otherwise small gesture larger and therefore funnier.

Fudd must now resort to that bailiwick of frustrated cartoon hunters: the easily escapable trap.

He makes the mistake of telling us (and, by earshot, the rabbit) of his intentions. We dissolve to what may be minutes or hours later.The CARROTS sign has neon piping, which Stallings accentuates with some modernistic stings. Fudd whistles and calls for the rabbit as if he were a simpering hound.

Rabbit hears the "c" word, and is all ears.

Sounds good to me!

In an example of the type of visual grandstanding that fills Avery's 1937/38 cartoons, and a sense of spatial depth that he would almost abandon in his prime M-G-M years, shadows and foreshortening heighten the effect of Elmer rushing to cover behind a tree. Plus, we get to see his nostrils.

Rabbit gives with his first sleight-of-hand trick.

Alarm sounds; confident hunter rushes to captured prey.

I believe we're back to Virgil Ross. Fudd's cap brim is conveniently torqued down so he can't see what we see.

Boastful Fudd trumpets his triumph to the rabbit, who leans against a tree in an iconic pose that remained part of his marketing profile for decades.Rabbit nods as Fudd gloats. It takes even longer for the nickel to drop this time...

Fudd receives a third kiss (this time on his little pink nose) as reality slows creeps into his consciousness...

"Uh oh," Bryan croaks as Fudd, sounding like a distressed spring mattress. He slowly turns to see what he has in his hand...

"Confidentially... well... you know," skunk (voiced by Blanc) says, with a knowing elbow nudge to the hunter's jowls. This appears to be another animator.

As Fudd lowers the skunk's fluffy tail, a squeak like an unoiled barn door accompanies it. Because that's funny.

Fudd has had it. Or so he thinks.

Unfazed by the twin barrels of the rifle, rabbit pushes them aside and talks calmly...

"Okay, Doc. I've had my fun, see?"

Fudd takes one on the chin from the butt of his rifle as rabbit continues...

"To show you I'm a sport..." (and I love the way Blanc pronounces that last word)...

"I'll give ya a good shot at me."

"Now you stand here..."

Rabbit breaks character with a dopey walk that shows this was still a persona-in-development. Stallings' derpy music accentuates the oddness of this moment. Devon IDs this as possibly being Paul Smith's work.

We're still a ways from the cool, confident stride that the mid-1940s Bugs Bunny would assume in the same situation.

Rabbit gives the OK signal then plugs his ears.

As both parties prepare for this point-of-no-return moment, nature intrudes.

(birds chirping in tree above)

We are reminded of what an intimate cartoon A Wild Hare is. Its predecessor, Elmer's Candid Camera, has a similarly small cast, but takes place out in the sunny open, with plenty of elbow room. Here, surrounded by thick woods, the actions and interactions are close-knit--almost claustrophobic. Our gaze is ground level, with little or no variance. The blue sky is only glimpsed through the clusters of trees and bushes. Thus, this cutaway to an up shot of a tree is startling.

"WHOA!HOLD IT!!"

A small but telling adjustment.

"Okay. Let 'er go!"

This might be the first time Elmer has ever fired a shotgun.

The shot sets the stage for one of the greatest scenes in animation, as beautifully animated by Robert McKimson..."Y'got me, pal... y'got me." Fudd's delight turns to chagrin as the rabbit's contortions seem real.

Robert McKimson's finest moment as an animator begins here. In concert with Mel Blanc's performance as the mock-dying rabbit, McKimson's work brings a gravity to the situation that creates nervous tension in the viewer. This is a joke, right? The little gray rabbit's not really dying, is he?

The tenderness in Fudd's eyes, and the concern on his face, often shown in a diabolically difficult downward-facing perspective, is masterful work in its own right. That it so effectively blurs the line between comedy and tragedy is powerful stuff. Like the Cab Calloway song sequences in the Fleischer cartoons Snow White (1933) and Minnie the Moocher ('32), this animation takes us, for a handful of seconds, to another place beyond farce, beyond Disney, beyond the limitations of the Hollywood cartoon.

If you are reading this and haven't watched the cartoon, do take another look at this scene. I don't wish to capture all of the rabbit's death throes here, but these poses tell the story. The coughing bits are beautifully done--by McKimson and Blanc. I love the moment when the rabbit's hand nudges Fudd's cheek. It's a thoughtful bit of animation that brings further weight to the scene.

In a particularly "McKimson" profile pose, Fudd is overcome with guilt and horror. As the rabbit's feet spring up, to suggest rigor mortis, the would-be hunter is devastated.

Bryan goes all-out in his expwessions of abject gweef. As he sobs and pounds a tree, we edge over to the rabbit, who is delighted with the result of his Oscar-worthy performance:

We are reminded that this is, after all, a Warner Brothers cartoon, and one by its chief director devoted to pricking holes in the tradition and pomp of Hollywood cinema. The glee on the rabbit's face is infectous. We just know he's going to give this nimrod the works! Rod Scribner gives this return to consciousness the joy it needs.

The rabbit's riposte is a simple act with an elaborate set-up. Virgil Ross handles this sequence,

The rump repositioning is a nice touch.

Fudd sails up the tree; hits branch with a gong sound, as in a carnival strength tester; plummets earthward.

Have a cigar.

Rabbit takes another screwball exit, perhaps spoofing-in-advance the ballet sequences of Walt Disney's Fantasia, which might have been the talk of the Hollywood animation community during the work on this cartoon.

The hunter has indeed been bagged by the game. And the game is up. Unlike the conclusion of the previous rabbit/Fudd cartoon, Elmer is not raving mad. He's crushed. Broken. What was raving, at the close of Elmer's Candid Camera, is now a wail of angst:

"Guns! Wabbit twaps! Cawwots!"

The hatless Fudd instantly reminds the viewer of Dopey, from Disney's Snow White. They share a similar head-to-body ratio--especially evident as Fudd walks away from the camera, lost in his anguish.

A weak ending could have happened a dozen different ways. A Wild Hare closes on a sublime note of victory for its title character. Rod Scribner finishes up the cartoon.

Gnawing on a carrot, dropping chunks from his mouth as he speaks, he looks at us and says:

"Can y'imagine anybody actin' like that?"

"Y'know...

"I t'ink th' poor guy's screwy."

To the air of "The Girl I Left Behind," an Elizabethan era ballad associated with the American Revolutionary War (to which the rabbit alludes by making an ad hoc fife out of his carrot), our anti-hero marches to his hole...

...and drops out of sight, back to his quiet life in the woods.

It's been noted that, upon viewing this film for the first time in many years, Tex Avery commented that he was surprised how few gags A Wild Hare had in it. I hope he felt some pride in that statement. The sublime balance of this film remains powerful, 78 years after its initial release. This is the cartoon that ushers out the busy clutter of late 1930s animation and looks forward to the streamlining of intent and technique that will distinguish the next decade of the art form.

Every element contributes to the film's success. The voice work of Blanc and Bryan keeps us riveted during this simple, elemental man vs. beast encounter. Carl Stallings' music, so in sync with the direction and animation that it becomes another character in the cartoon, supports every action and reaction with solidity and assurance. And the animators, who brought Avery's concepts to Technicolor life, and who had been dramatically improving over the last year, give their all to each drawing here.

A Wild Hare feels like it could be The Last Cartoon--the animated film to end them all, and a sophisticated and potent salvo against the mainstream. Its effort obviously exhausted Avery. He falls back on the tired-and-true (that's no typo!) spot-gag format for his next two efforts, and will crank out four more in that vein amidst fair-to-great works for the remainder of his Schlesinger stay.

Avery still had far to go to perfect his comedic/filmic vision. Perhaps he never reached the ideal he had in his head. But the quantum leap from Porky's Duck Hunt--the 1937 birth of this notion--to the beautiful playbook of A Wild Hare is a great feat. That earlier cartoon remains one of it's maker's true classics, but the honed-down focus of this film makes it a major milestone in the development of the art form of animation. It's a magic moment that could only happen once. Never did a movie-maker so have the element of surprise in his favor, and so aptly use it to such great effect.

Avery still had far to go to perfect his comedic/filmic vision. Perhaps he never reached the ideal he had in his head. But the quantum leap from Porky's Duck Hunt--the 1937 birth of this notion--to the beautiful playbook of A Wild Hare is a great feat. That earlier cartoon remains one of it's maker's true classics, but the honed-down focus of this film makes it a major milestone in the development of the art form of animation. It's a magic moment that could only happen once. Never did a movie-maker so have the element of surprise in his favor, and so aptly use it to such great effect.

A Wild Hare was the subject of a traced comic book version--one of several that appeared in the first issues of Dell Comics' Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies title. A far cry from the quality of their other cartoon-anthology comics (Our Gang Comics, New Funnies, Walt Disney's Comics and Stories), LT&MM housed some of the worst animation-based comic book art of its era. Here's the first page of the story. (Note the replacement of "a" with "the"--an unfortunate trend for this cartoon.)

Note how all humor and appeal is leached out of each panel. The stories were created with the aid of a moviola and some tracing paper. How's that for an anti-climax?

______________________________

Thanks to Mark Kauser, Devon Baxter and Thad Komorowski for their thoughts on animator identification in this landmark cartoon. These three fellows have been helpful throughout this blog's existence, even when our opinions on at least one cartoon were at odds. I'm grateful to them, and to the regular commentators of this blog. Thank you all.

AUDIO BONUS: radio re-enactment of initial Fudd/Bugs meeting, voiced by Blanc and Bryan... https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4JSzOojgumo (thanks to Devon Baxter for providing this link)

UP NEXT: Airborne spot-gaggery: Ceiling Hero.

P.S.: thanks to those who have posted comments on this post. I can't post them until I get my laptop back, which should happen this coming week.

A masterful job. I have one criticism, though: using words like "ofay", "honky" & even "entitled" in describing the "white" Fudd puts a bullshitty "Aren't caucasians just awful?" spin on your otherwise well-written piece.

ReplyDeleteThat aspect aside, I most enjoyed your analysis of Bugs' acting effeminate & cross-dressing as a disorienting weapon. It's very clear as the years go on that he likes girl wabbits...a lot...but he's in touch with his feminine side. ;>

I've always felt Bugs vs. Elmer had a kind of tacit racial element to it--the dim white hunter vs. the quick-thinkng non-human prey--and Bugs is clearly no honky! That is one aspect of Avery's ALL THIS AND RABBIT STEW that makes the film such a failure. (That will be an interesting one to write about for certain!) Just trying some ideas out here. You gotta take risks and try stuff out sometimes.

DeleteI always saw Elmer as a dim HUMAN. I honestly don't see how the Bugs/Elmer dynamic had any racial element, save the idea of Bugs vs. the human race. But these are minor quibbles compared to your excellent analysis of the most important WB cartoon of the era. Keep up the good work.

DeleteI reckon this is one of the only times where Avery fully delved into character development, something he wasn't interested in. The mood and atmosphere is somewhat unusual for an Avery film of this time frame, but it's truly a landmark film in animation history.

ReplyDeleteThese commentaries are very insightful. It'd be cool to see them formatted in book form. There needs to be a newer book on Avery's life and work.

J Lee left this fine message which accidentally got deleted. Here's what he said:

ReplyDeleteThe 1939/1940 cartoon season was really an on-screen class in animation -- Avery by 1938 knew how to do funny gags, but the next two years were spent absorbing the innovations of the Disney studio into creating animation where the ability to create tangible, living personalities out of the animation becomes the basis of the gags. The growing pains of the sometimes leaden pacing and overly-detailed animation would be streamlined and harnessed with this cartoon, before things began speeding up again after that, but now with characters who had fully rounded personalities.

Fudd may be childish, but "A Wild Hare" gives us a very adult Bugs, where part of the fun is seeing his thought processes and machinations at work (which had a bit of an antecedent a few months earlier at the studio in "You Ought To Be In Pictures", which wasn't as much as a seminal change in Daffy as Avery's Bugs was was Ben Hardawy's rabbit, but does for the first time give Daffy adult, rational thought processes for actions that would blow up in his face at the end of the cartoon). In Avery's case -- and thanks to McKimson's amazing pantomime animation -- we're over two minutes into the cartoon, and before we've ever seen Bugs' face or heard Bugs' voice, he is Bugs Bunny as audiences 75 years in the future would know him, simply from a battle between a hand and arm vs. a shotgun barrel over a carrot.

The other thing about "A Wild Hare", as the next handful of rabbit cartoons as well as others by Avery would show, is the studio itself might have known it had something special, but didn't quite know how to go about exploiting it at first. As with Daffy scamming Porky in Freleng's live-action cartoon, cartoon shysters were supposed to get their comeuppance by the iris out, and the studio was unsure of allowing Bugs to emerge fully triumphant at the end of his first year or so of regular cartoons, while Tex's next two efforts with slick characters versus a dumb opponent, Avery frames the action so the audience's sympathy isn't with the savvy huckster, it's with the dumb opponent (Willoughby). That difference is why Bugs lives on, while the fox and quail with Bugs' attitude never saw life again after their solo cartoons.