DVD-Blu-Ray Availability: Looney Tunes Golden Collection Vol. 5 DVD set

You may view the complete version of this cartoon HERE.

Still riding high, Avery & Co. return to one of the director's pet projects--trashing Disney-style fairy-tale cartoons. Light on narrative (much like Uncle Tom's Bungalow and Little Red Walking Hood), The Bear's Tale is a fourth-wall demolition derby, with the director adding his gleeful voice work to a spicy, chaotic stew.

I'd like to know who really wrote this cartoon. It's far too sophisticated, cool calm and collected to have come from the likes of "Bugs" Hardaway. I assume this title card is a typical example of Leon Schlesinger's rotating credit system.

The cartoon manages to avoid actual animation for about a minute, via novel credits that make maximal use of still images. Pages keep turning, as narrator Robert C. Bruce fools us into getting all snuggly and comfortable--as does the music of Carl W. Stalling, who was by now a master of easing us in via familiar snatches of classical and popular tunes.

Avery kids journeyman director Mervin LeRoy, who helmed everything from Little Caesar (1930) to The Bad Seed (1956), and had a hand in a long list of enjoyable classic Hollywood product.

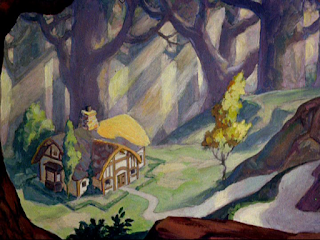

Robert C. Bruce opens, against an image that was likely repellent to Avery, but done up convincingly enough to fool the weaker minds in the audience: "Once upon a time, long, long ago..."

"in the midst of a beautiful green forest..."

(actual animation begins)

"...there was a quaint little cottage..." Avery and Stalling make cloying pauses between each passage of Bruce's narration, filled with familiar musical themes and with the intent of overdoing the schmaltz. Bruce continues, as Avery drops his players into the cottage interior:

After their rear entrance, we see them from the other side of the table.

Each has a little bit of business to establish their character, or lack thereof...

(self-satisfied smart-ass)

(runs the household)

(tuned out)

The requisite three bowls of porridge drop from above:

Porridge, upon arrival, proves too hot to enjoy.

Dad Bear chortles with condescension: "Heh heh heh... soup's too hot!"

By the time of this cartoon, the classic 1940s Hollywood animation style is almost set. Some Warners cartoons will still look a bit wonky until 1942 (Hiawatha's Rabbit Hunt, anyone?), but the improvement of the animation, studio-wide, is remarkable. Avery's animation crew was capable of great subtlety and expression, and never failed to give each scene some fine touches, even when the director's intent was to savage the source material and get laughs from the audience. The goggle-eyed, more Art Deco-influenced animation of 1937 and '38 seems a world away from this work.

Back to our cartoon-in-progress:

Super-fast truck-in/cut to a close up of the hot water faucet, its handle reversed.Papa Bear's solution to everything is to turn it into an unfunny joke. "Hot stuff," he quips.

Ma Bear suggests the family take a ride while the porridge cools. Then she dons her hat, in a moment worthy of M. C. Escher or Max Ernst...

The front door of the bears' cottage is custom-made for their different sizes:

"And into the beautiful green forest..."

In this formal, deliberate cartoon, Avery, Stalling and Bruce collaborate on a series of repetitive moments--faux-Disney multiplane camera moves, "Tales of the Vienna Woods" and recurring words in the narration. Avery never wastes a moment to show the differences in life approach by these storybook bears...Papa and Mama take it easy while Baby Bear earns every bite of his porridge. The short, frenzied animation cycle of the tot's pedaling makes his toil clear.

"Meanwhile..."

Enter Goldilocks, doing an inane skip set to a nauseous arrangement of "A Tisket, A Tasket."

She approaches what we assume to be the Three Bears' home...

knocks with great force...

and, via a series of exquisitely timed whip pans of the interior...

Avery does a shock-reveal... it's the wolf from "Little Red Riding Hood," voiced by Mel Blanc, in one of his latest entrances to a classic WB cartoon, right near the four minute mark.

Unwise to this plot twist, Goldilocks enters.

A lot of information is crammed into the next minute of this cartoon. It's quite striking, during this minute, how well information is conveyed through dialogue and body language. None of it is remarkably funny, but it allows Avery & Co. to carefully cross-pollinate two fairy tales into one meta-narrative--itself a shell for the chaotic comedy that, by 1940, was the essence of Warner Brothers cartoons.

Wolf is shocked to see Goldilocks; "Hey, what is this--some kind of a frame-up?" he snarls.

Still oblivious, Goldilocks sing-songs, "Isn't this where the Three Bears live?"

Wolf mocks her cutesy delivery and shows her the door.

"This is Gran'ma's dump," Wolf says, "an' I'm waitin' for Red Ridin' Hood!"

"What's Red Riding Hood got that I haven't got?" asks an

offended Goldilocks as she exits, stage right.

Wolf scoffs before it dawns on him: food is food. What was he thinking?

Off to the bookshelf, which contains a convenient selection

of cartoon fairy-tale favorites, including (of course)...

His memory refreshed, wolf-in-nightgown hails a taxi...

"I'll take care of any tickets," he tells the cabbie, in an Avery-characteristic aside.

The subtleties of perspective animation still dogged 1940 animators.

Fade to black. Fade right back in. Wolf breaks and enters, belly-dives into Baby Bear's bed.

Back to the bears, who are ready for some edible porridge.

Papa Bear imitates a police siren, for his own amusement and no one else's...

and receives Mama's vicious backhand.

He cringes--a telling sign of the relationship dynamic of Papa and Mama Bear.

Cut back to Goldilocks, who saunters towards (and into) the Bears' cottage, while an irritated Wolf drums his fingers upstairs...

By this time, the formalities of The Bear's Tale begin to wear on the viewer. This system has been set in motion, and must continue to its inexorable end. Perhaps Avery realized this, for the cartoon takes a welcome detour. Bruce drags out his shtick about the beautiful forest, but the camera moves away from the cottage, to reveal Little Red Riding Hood. She, of course, gets a rousing version of that Stalling favorite, "The Lady in Red..."Red susses out the house, and finds a note with a subtle dig at Liberty magazine (the first, non-libertarian version) and races for the phone.

When a character makes a phone call in an Avery cartoon, as in Thugs With Dirty Mugs, you just know the fourth wall is going to get dinged. Here is one of the director's more delightful variations on that pet theme...

In her grating voice, Red relates her discovery...

then breaches the double-exposure line to hand Goldy the wolf's note.

Unfazed by this news of her possible demise, Goldy chirps her thanks. The two heroines shake hands and exit...In one of Avery's sublime scene toppers, Goldilocks returns to fish a coin out of the pay phone's return slot.

It's a private moment, and she seems to have forgotten that the camera's always running in Averyland. She looks sheepish, shocked and embarrassed, and slinks out of sight.

She's never seen again. As with many of Avery's best comedic moments, this bit didn't have to be there, but its inclusion makes this cartoon all the better. Now, all we have to do is to get those three bears back into their house (drums fingers)...

Porridge tampering is discovered by all.

"an' they ate mine all up," Baby whines.

Must be drafty upstairs; the wolf lets out one of the great cartoon sneezes.

Homeowners are startled.

A sophisticated camera move follows the bears under the table, as Papa pretends to have cojones:

"I'll go upstairs an' take care of that crook."

In a flourish of rich character animation, Papa reveals he's in on the joke.

"I know there ain't no robber up there; just a little tiny girl named Goldilocks."

"I read this story last week in Reader's Digest."

As usual, Papa is his own best audience.

Papa enters the bedroom and speaks with condescension (and a touch of perviness) to the lump in the bed her perceives to be that "cute li'l curly-headed rascal..."

Color him surprised!

This is beautiful stuff, as the Wolf leans closer into Papa, who spasms his way through a couple of small heart seizures, as stammered to perfection by Avery...And, alas, the cartoon abandons at least one important plot strand--where the hell did Goldilocks go? Was she so dented by her on-screen humiliation that she left the cartoon? We'll never know for certain, for the proceedings must end in the highly stylized way they began, with Bruce stepping back in as narrator after one final burst of manic, scenery-trashing action:

"So, over the hill went the Three Bears..."

"...the Papa bear..."

"the Mama bear..."

"and the little bear behind."

The sum of The Bear's Tale doesn't add up to its parts, which impress, from scene to scene, with ther relaxed, off-handed feel. Unlike the Avery of 1937, who turns gleeful cartwheels as he disembowels the standards of Hollywood film-making, the director moves slyly, stealthily here from moment to moment.

As happens throughout Avery's career, in his devotion to shattering the wall of trust between film-makers and audience, he loses sight of a cohesive narrative. Story was never one of Avery's strong suits, or stated goals, as a cartoon film-maker. When he does pay attention to his narratives, they can be quite solid and detailed. They are most often a means to an end for him. Getting a reaction from his audience--of laughter, surprise or confusion--was Avery's endgame.

Avery, like Bob Clampett and Friz Freleng, is an entertainer, but the amusement value of his cartoons typically comes with a price. His richest and most complex comedic ideas can still rattle us, 80-something years later, and despite constant imitation and quotation. What most of Avery's imitators don't get is the utter coolness of his presentation, from 1940 on. At the end of the 1930s, Avery learned how to underplay his hand. Though his name evokes images of wild, tongue-lolling double-takes, spastic motions and aggravated assault, there is a level head behind it all.

Avery's cool will reach an early culmination with A Wild Hare (just two cartoons away!), then further refine his MO as he transitions from Schlesinger to M-G-M. We see, in The Bear's Tale, a savvy comedic mind that knows what it's doing and where it's going. This was Avery's 42nd cartoon for Schlesinger. Each of his previous cartoons was a stepping stone towards refining his comic vision. He will sometimes lose his footing--as in the spot-gag cartoons yet to come. But his mis-steps still merit study and reflection. Few cartoon filmmakers took such risks.

NEXT: Back to Spotgagville with A Gander At Mother Goose.

Thanks for the new post, Frank! That's Rod Scribner's animation on the scenes where Papa Bear discovers the wolf in Goldilocks's place in the bed upstairs. So the credits aren't completely wrong.

ReplyDeleteThe best thing (to me) about Avery's unit during the late 30s, early 40s is how well design the characters look (which, of course, furthers the joke). it's always been amazing seeing how strong and controlled Rod Scribner's animation here and previous entries like Bars and Stripes Forever compared to what came later when he migrated to Clampett's unit (until he went to Mckimson's unit).

ReplyDeleteI'm glad that you made a fine recovery. A Gander At Mother Goose is actually one of my personal favorites, so I'm interested in seeing how you tear down the rest of these spot gags efforts (I'm pretty sure you'll praise A Wild Hare down the road..).

Warners is still in it's 1939-40 period of slightly over-detailing the characters here, compared to the streamlining that would come later (with Bugs being one of the earliest examples). But it works -- the extra detail fits with both the slower narrative and with Johnny Johnson's lush backgrounds that would continue through the rest of Tex's time at the studio (in a way, this is almost like Avery's lite version of Hugh Harmon's concurrent work at MGM in terms of the background, detail and improving animation quality. The slower pace lets you soak all that's on screen in as with Harmon's Three Bears cartoons, except that Tex was more interested in entertaining the audience with the unexpected gags, while Hugh was more into impressing the audience with his near-Disney animation).

ReplyDeleteLove this blog. Hope you are well.

ReplyDeleteIf it feels too "smooth and calm" for Ben Hardaway's writing, then my guess would be that Tex wrote most of it himself. Since he was such a workoholic and always way too dedicated to his cartoons, that makes sense to me.

ReplyDelete