DVD-Blu-Ray Availability: none

You may view this cartoon HERE.

The third forward-reaching, formally playful cartoon in a row from the Fred Avery unit, Johnny Smith and Poker-Huntas further accelerates Avery's often radical study of the relationship between the pre-existing (the 7:52 of this animated film, projected on celluloid) and the unpredictable (the paying audience who took this cartoon in as part of a typical evening's movie fare).

This is the first of Avery's Schlesinger cartoons that really feels like his M-G-M work. Two films from wartime bear an obvious resemblance to JSaPH (I refuse to re-type that title)--the regrettable 1944 Screwy Squirrel cartoon Big Heel-Watha and 1945's Jerky Turkey, By no means is this cartoon as technically adroit, nor sophisticated in its timing, as those later works. A general vibe, familiar to his M-G-M masterpieces of the 1940s, comes to the forefront of Avery's work here.

That vibe will sustain itself through a handful of great cartoons in the year ahead, despite a string of tired topical spot-gag films. This, thank heavens, is not one of those.

Warner Brothers' live-action features of the period often begin with an post-credits preface that either sets the mood of the film to follow, or celebrates the historical source material upon which utter fiction was spun. These moments' self-congratulatory mood was catnip for Avery's sense of humor:

Bragging rights about alleged Mayflower lineage was, in the 1930s, still a nationally shared running gag, and this perverse exaggeration would have gotten a laugh from viewers. Despite the animated ship's lumpen movement, especially in silhouette, the gracefulness of Avery's film-making in this period still impresses.

Avery and his gagmen play upon every grade-school cliche of pilgrim history.

Avery's pet gag, in late 1938, seems to be "something old + something new"--finding humor in anachronisms. Some of his most elaborate, expansive variants on this theme will be seen later in this cartoon.

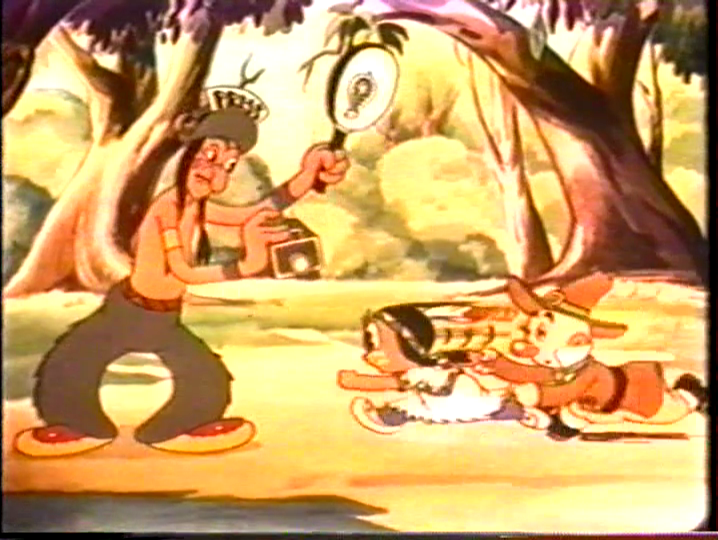

No time wasted; Elmerhead, our would-be hero, is introduced,

with live action-style large block letters announcing his role.

Elmerhead interacts with the on-screen legend...

by knocking the letters down, as a row of dominoes. Carl Stalling

obliges with a peppy xylophone obbligato.

obliges with a peppy xylophone obbligato.

Satisfied with his vandalism, Elmerhead (voiced by Mel Blanc)

asserts historical bragging rights:

asserts historical bragging rights:

"I came over on da Mayflowah!"

Something catches his eye.

This is Tex Avery's America--laden with neon signs and

intrusive advertisements, even in 1620.

intrusive advertisements, even in 1620.

A busy dissolve reveals that we're in a world substantially

different from grade-school history books.

different from grade-school history books.

At this point in his career, Avery has a set pattern: introduce a new

setting, then pound the viewer with sight gags. Once we're acclimated

to a 17th-century world of late '30s roadsters, paved streets and

shopping centers, the onslaught begins:

Herein, an authentic (and cleverly dispatched) Mohawk

haircut is given, animated by Irv Spence:

haircut is given, animated by Irv Spence:

This last moment leaves the screen a split second after it

appears, the better to cram in another gag...

Minnie is less than jolly. After her acidic "ha, ha..."

she sticks out her tongue at the audience.

Cut to a truck-and-reveal gag...

that isn't funny, per se, but follows a line of logic.

Next is one of my favorite Avery moments. As with so many

of his set-pieces, form simply follows function. If a brave's headpiece

looks like a turkey's ass, make it one--and have the bird be

part of the lookout effort. This is the kind of gag set-up a

Mel Brooks (in his brief prime) would've killed for:

After this brain-storm, Avery dips back a few films, and

re-does a gag from Egghead Rides Again:

Comedy Rule: Always show the source of a character's surprise take.

The next gag, clever despite its inherent clunkiness,

smacks of "Bugs" Hardaway:

smacks of "Bugs" Hardaway:

Avery revisits early-sound cartoon logic in this scene.

From the Van Beuren "Cubby Bear" cartoon Indian Whoopee (1933).Central to an understanding of Avery is the influence silent and early sound cartoons had on his sense of humor. His was a determined effort to not let such moments disappear from animation, in the wake of the smothering influence of Walt Disney.

Though this Van Beuren cartoon was a half-decade old, so much had occurred in animation between '33 and '38 that it might have seemed ancient, compared to The Old Mill or Snow White. Avery understood that there was still a power to this pre-Disney way of thinking. His body of cartoons offer a reactionary-but-innovative rejection of the softening influence of realism in his chosen art form.

On that note, we see Avery recycle another recent gag--from Cinderella Meets Fella.

Native American drums replace familiar telephone bells.

Familiar shave-and-a-haircut rhythm tops gag.

Mel Blanc-voiced "ugh-ugh-ugh"s get Chief

vexed. He gets up from his 1938 desk and office

chair to address his tribe.

vexed. He gets up from his 1938 desk and office

chair to address his tribe.

Avery will revisit this sequence in Big Heel-Watha. Here, the moment is invested

with more spectacle and filmic grandeur. By 1943, Avery had, for better or

worse, gotten mainstream cinema out of his system, and moved into another realm.

The M-G-M cartoon has a prim, proper newscaster Native American, to

translate its chief's ugh-ughs into sensible sentences. Here, a similar figure

serves as warm-up act for Chief Philco Slogan.

translate its chief's ugh-ughs into sensible sentences. Here, a similar figure

serves as warm-up act for Chief Philco Slogan.

Increased intensity in body language works well

in this bit of business.

in this bit of business.

One "Ugh!" is all it takes...

...and his constituency is stirred to action.

Whinemeal...

the pilgrims land.

Elmerhead invites injury with his "last one off's a rotten egg" taunt.

So much for that brilliant plan...

We move on to the obligatory suspenseful pilgrims-explore-woods bit.

Already, signs are game-changers in Avery's world.

I just noticed that Elmerhead attaches himself to the

legs of another pilgrim, as he cowers in fear.

legs of another pilgrim, as he cowers in fear.

Yep, you guessed it. It was probably funny in 1938.

Elmerhead's "I'm an alumin-us!" response is still

funny, but it's not the correct answer.

funny, but it's not the correct answer.

Chief is newly pissed.

Then a harbinger of a new sensibility enters the picture.

This gag can be seen as a cost-cutting time-filler. Each

second the sign is on-screen means 24 frames of animation

that don't have to happen. But it shows Avery's comfort

level in disrupting the unspoken "entertain me" contract

between film-maker and audience.

A follow-up statement, intended for Elmerhead, appears.

"Oh, to be sure. That's okay. I'm under contract, anyway!"

"Besides, I'm too fast for these boys. These redskins could

NEVER catch me! [cackles]"

Famous last words, anyone?

We fade in/truck back to reveal John Smith's sad fate.

Only random scraps of original work material from these late 1930s Schlesinger cartoons exist, but here's something of interest. This is a cel of the static background figures of this scene. It demonstrates the technique, mentioned in last post, of inking certain figures with a neutral earth tone, instead of the customary black line. It also shows the intended original colors, compared to the admittedly sub-par print of JSaPH that circulates today:Elmerhead delivers an in-joke line, from the Schlesinger studio's on-hand projectionist, that Bob Clampett, and other directors, would make a Warners cartoon trope through the 1940s: "Agony!"

A happy executioner!

A jeering section, crudely animated, chants, "Give 'im

the ax, the ax, the ax!"

Elmerhead protests, and is about to cite his

historical importance. The natives are already

sick of these claims, and razz him:

"On The Mayflower! Nyaah!"

We truck in to the Chief, who leans forward towards

the audience, and mutters, "Gee, dat stuff gets me!"

Avery slips in a morbid-but-sensible gag, again forecasting

the humor sensibility of Jacques Tati:

Pre-destination makes the heart grow fainter.

Since the neck already says to do, it the axeman spits on his

hands and readies that final swing of the blade.

An abrupt dissolve/truck shifts the scene:

Poker-huntas listens to Walter Winchell (on her Philco?)

as he delivers the bad news about John Smith,

as though it were a crucial play in a football game.

Thanks to a friend of this blog, I'm happy to share with

you an original cel painting from this sequence, before

we continue further on:

as he delivers the bad news about John Smith,

as though it were a crucial play in a football game.

Thanks to a friend of this blog, I'm happy to share with

you an original cel painting from this sequence, before

we continue further on:

"Gee, I'd better get going," Poker-Huntas notes.

"Yes, you'd better, sister--if you want this picture to have a happy ending!"

This matter-of-fact self-awareness is now Avery's unique

terrain--a POV that will be shamelessly copied by

other cartoon-makers, most often minus a scintilla of skill.

P-H jumps in her late-model roadster and zooms off.

D. W. Griffith-worthy cross cutting creates a lampoon of suspense.

In a hurry? Just do a hit-and-run!

Never pass up a chance for good publicity.

Via coupe, J and P split the scene.

The inevitable chase scene--a bane of cartoons no one

can escape. But Avery can delay it with an unexpected twist:

The natives count to 50, as in hide and seek.

They, too, choose convertibles as their mode of transport.

Perfect time for a throwaway gag of another Avery

genus: chaos inadvertantly turned to order.

This print is too dicey to freeze-frame during scenes of

fast action, but today's second piece of original art comes

from the moment of the cars' impact with the wood and stone:

If 1620 has radios, telephones and cars, it must also

have laws, so the traffic light seems apt here:

And laws are meant to be disobeyed.

Irv Spence's animation doesn't dominate this cartoon, as it has in

the last few, but he does contribute this daffy bit:

the last few, but he does contribute this daffy bit:

Nothing like getting run over for a gag capper!

Anachronistic car chases have been with Avery from his

first cartoon, Gold Diggers of '49. These sequences

provide milestones to his growth as a humorist and movie-maker.

By this time, there's not much distance between the

following sequence and many of his M-G-M cartoons:

Native Americans choose effort-saving short cut.

Avery (and many others) enjoyed this speed gag:

What happens next is wholly unexpected and delightful.

"Hey, fellas! Ain't this some fun?"

"Yeah! Let's do it some more!"

John and Poker-Huntas aren't concerned.

P-H babbles a lengthy summary of the rest of the cartoon, which adds a layer of

cynicism to her self-awareness. They'll never get us, so don't worry!

Johnny nags her to stop spilling the works. "Let 'em guess!"

True to her word(s), they escape.

With the aid of a boot-shaped pusher-offer, they're en route.

The sweethearts now kindly regard their adversaries...

Elmerhead has sweet lovin' on his mind.

Watch that feather!

Fade out; fade in on domestic bliss.

In the cartoon's final gag, historical accuracy is

jettisoned. The native tribes who greeted the

first pilgrims were the Massasoits and Wampanoags.

Since neither tribe had a well-known book named

after them, Avery's gag is more practical.

Poker-Huntas: Oh, ye-yah?

On this merry scene of octuplets, we iris out...

...and everything comes out in the end.

JSaPH, and its two immediate predecessors, are high-water marks in Tex Avery's early career. With each cartoon, he edges closer to the sublime sensibility that guides his M-G-M cartoons. Animation is still in limbo--no longer the streamlined imps of the early 1930s, nor the sophisticated figures of the '40s.Though we may find ourselves impatient with cartoons of the late 1930s, they are landmarks in a quiet revolution--strides away from the cute, cloying and inoffensive, and ramp-ups to the brassy, expressive zenith of the coming decade. Not every step in this period was carefully chosen. In moments of blind imitation, lesser directors fell short of the ideal pursued by Avery, Friz Freleng and Bob Clampett (with Chuck Jones soon to follow).

The best animations of this period--and JSaPH is among them--boldly traffic in a game of wits with their audience. In Avery's better cartoons, that audience is assumed to be smart and perceptive--able to catch the multiple fast balls that sizzle by. Avery has yet to attain the hyper-fast tempo of his M-G-M efforts, but he's very close. A lot occurs in this cartoon short, though its plot is just a container for gags and formal mischief.

A strong personality informs this cartoon, as with Schlesinger's other talented directors. No longer are their cartoons anonymous and interchangeable.

Avery's next two films will fall short of the ideal attained in this trinity of small masterworks. Their relative weakness is leavened by clever, sometimes innovative film technique. (The next cartoon exists in a beautiful restored print, so the end result will be kinder to the eyes, as well).

UP NEXT: Tur-r-r-r-r-key mit all der tr-r-r-r-r-r-immings: Daffy Duck in Hollywood.

Throwaway gag: note the brand-name of motorcycle the traffic cops have. The company was still in business at the time, before succumbing to Harley-Davidson.

ReplyDeleteThis cartoon, along with the last half of "Cinderella Meets Fella" and the two Cal Dalton cartoons -- "A Lad In Baghdad" (with Cal Howard) and "Count Me Out" (with Hardaway), seem to be conscientious efforts to try and make a character out of Egghead (or, if you prefer, Elmerhead) who could carry a story as its main character, as opposed to be merely the source of gags by his incongruity or a foil for Tex's Daffy Duck.

ReplyDeleteJS&PH is really a step towards the more aggressive-yet-sane personality animation that would characterize Warners from 1940 onward, but as others have noted, there's just something a little too bizarre/goofy about Egg/Elmer's design to put him across as any sort of 'heroic' character. So he would go back to the spot gag shorts for his final appearances, while Tex would tinker around with a dog featuring Arthur Q. Bryan's voice in his next attempt to find a new character to fit around his wild gags.